What a silly thing love is! said the student as he walked away. It is not half as useful as logic, for it does not prove anything, and it is always telling one of things that are not going to happen, and making one believe things that are not true. In fact, it is quite unpractical, and, as in this age to be practical is everything, I shall go back to philosophy and study metaphysics. So he returned to his room and pulled out a great dusty book, and began to read.

The daughter of the Professor was sitting in the doorway winding blue

silk on a reel, and her little dog was lying at her feet.

“You said that you would dance with me if I brought you a red rose,”

cried the Student. “Here is the reddest rose in all the world. You will

wear it to-night next your heart, and as we dance together it will tell

you how I love you.”

But the girl frowned.

“I am afraid it will not go with my dress,” she answered; “and, besides,

the Chamberlain’s nephew has sent me some real jewels, and everybody

knows that jewels cost far more than flowers.”

“Well, upon my word, you are very ungrateful,” said the Student angrily;

and he threw the rose into the street, where it fell into the gutter, and

a cart-wheel went over it.

“Ungrateful!” said the girl. “I tell you what, you are very rude; and,

after all, who are you? Only a Student. Why, I don’t believe you have

even got silver buckles to your shoes as the Chamberlain’s nephew has”;

and she got up from her chair and went into the house.

“What a silly thing Love is,” said the Student as he walked away. “It

is not half as useful as Logic, for it does not prove anything, and it is

always telling one of things that are not going to happen, and making one

believe things that are not true. In fact, it is quite unpractical, and,

as in this age to be practical is everything, I shall go back to

Philosophy and study Metaphysics.”

So he returned to his room and pulled out a great dusty book, and began

to read.

[Picture: Decorative graphic of nightingale and rose]

The Selfish Giant.

[Picture: The Selfish Giant]

EVERY afternoon, as they were coming from school, the children used to go

and play in the Giant’s garden.

It was a large lovely garden, with soft green grass. Here and there over

the grass stood beautiful flowers like stars, and there were twelve

peach-trees that in the spring-time broke out into delicate blossoms of

pink and pearl, and in the autumn bore rich fruit. The birds sat on the

trees and sang so sweetly that the children used to stop their games in

order to listen to them. “How happy we are here!” they cried to each

other.

[Picture: Decorative graphic of children in garden]

One day the Giant came back. He had been to visit his friend the Cornish

ogre, and had stayed with him for seven years. After the seven years

were over he had said all that he had to say, for his conversation was

limited, and he determined to return to his own castle.

LORD ILLINGWORTH: The soul is born old but grows young. That is the comedy of life.MRS ALLONBY: And the body is born young and grows old. That is lifes tragedy.

What would you do if she struck you across the face with her

glove?

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Fall in love with her, probably.

MRS. ALLONBY. Then it is lucky you are not going to kiss her!

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Is that a challenge?

MRS. ALLONBY. It is an arrow shot into the air.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Don’t you know that I always succeed in whatever I

try?

MRS. ALLONBY. I am sorry to hear it. We women adore failures. They

lean on us.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. You worship successes. You cling to them.

MRS. ALLONBY. We are the laurels to hide their baldness.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. And they need you always, except at the moment of

triumph.

MRS. ALLONBY. They are uninteresting then.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. How tantalising you are! [_A pause_.]

MRS. ALLONBY. Lord Illingworth, there is one thing I shall always like

you for.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Only one thing? And I have so many bad qualities.

MRS. ALLONBY. Ah, don’t be too conceited about them. You may lose them

as you grow old.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. I never intend to grow old. The soul is born old but

grows young. That is the comedy of life.

MRS. ALLONBY. And the body is born young and grows old. That is life’s

tragedy.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Its comedy also, sometimes. But what is the

mysterious reason why you will always like me?

MRS. ALLONBY. It is that you have never made love to me.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. I have never done anything else.

MRS. ALLONBY. Really? I have not noticed it.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. How fortunate! It might have been a tragedy for both

of us.

MRS. ALLONBY. We should each have survived.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. One can survive everything nowadays, except death, and

live down anything except a good reputation.

MRS. ALLONBY. Have you tried a good reputation?

LORD ILLINGWORTH. It is one of the many annoyances to which I have never

been subjected.

MRS. ALLONBY. It may come.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Why do you threaten me?

MRS. ALLONBY. I will tell you when you have kissed the Puritan.

[_Enter Footman_.]

FRANCIS. Tea is served in the Yellow Drawing-room, my lord.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Tell her ladyship we are coming in.

FRANCIS. Yes, my lord.

[_Exit_.

The truth is rarely pure and never simple.

Cecily, who addresses me as her

uncle from motives of respect that you could not possibly appreciate,

lives at my place in the country under the charge of her admirable

governess, Miss Prism.

ALGERNON.

Where is that place in the country, by the way?

JACK.

That is nothing to you, dear boy. You are not going to be invited . . .

I may tell you candidly that the place is not in Shropshire.

ALGERNON.

I suspected that, my dear fellow! I have Bunburyed all over Shropshire

on two separate occasions. Now, go on. Why are you Ernest in town and

Jack in the country?

JACK.

My dear Algy, I don’t know whether you will be able to understand my

real motives. You are hardly serious enough. When one is placed in the

position of guardian, one has to adopt a very high moral tone on all

subjects. It’s one’s duty to do so. And as a high moral tone can hardly

be said to conduce very much to either one’s health or one’s happiness,

in order to get up to town I have always pretended to have a younger

brother of the name of Ernest, who lives in the Albany, and gets into

the most dreadful scrapes. That, my dear Algy, is the whole truth pure

and simple.

ALGERNON.

The truth is rarely pure and never simple. Modern life would be very

tedious if it were either, and modern literature a complete

impossibility!

JACK.

That wouldn’t be at all a bad thing.

ALGERNON.

Literary criticism is not your forte, my dear fellow. Don’t try it. You

should leave that to people who haven’t been at a University. They do

it so well in the daily papers. What you really are is a Bunburyist. I

was quite right in saying you were a Bunburyist. You are one of the

most advanced Bunburyists I know.

JACK.

What on earth do you mean?

ALGERNON.

You have invented a very useful younger brother called Ernest, in order

that you may be able to come up to town as often as you like. I have

invented an invaluable permanent invalid called Bunbury, in order that

I may be able to go down into the country whenever I choose. Bunbury is

perfectly invaluable. If it wasn’t for Bunbury’s extraordinary bad

health, for instance, I wouldn’t be able to dine with you at Willis’s

to-night, for I have been really engaged to Aunt Augusta for more than

a week.

A thing is not necessarily true because a man dies for it.

It is the only perfect key to

Shakespeare’s Sonnets that has ever been made. It is complete in every

detail. I believe in Willie Hughes.’

‘Don’t say that,’ said Erskine gravely; ‘I believe there is something

fatal about the idea, and intellectually there is nothing to be said for

it. I have gone into the whole matter, and I assure you the theory is

entirely fallacious. It is plausible up to a certain point. Then it

stops. For heaven’s sake, my dear boy, don’t take up the subject of

Willie Hughes. You will break your heart over it.’

‘Erskine,’ I answered, ‘it is your duty to give this theory to the world.

If you will not do it, I will. By keeping it back you wrong the memory

of Cyril Graham, the youngest and the most splendid of all the martyrs of

literature. I entreat you to do him justice. He died for this

thing,—don’t let his death be in vain.’

Erskine looked at me in amazement. ‘You are carried away by the

sentiment of the whole story,’ he said. ‘You forget that a thing is not

necessarily true because a man dies for it. I was devoted to Cyril

Graham. His death was a horrible blow to me. I did not recover it for

years. I don’t think I have ever recovered it. But Willie Hughes?

There is nothing in the idea of Willie Hughes. No such person ever

existed. As for bringing the whole thing before the world—the world

thinks that Cyril Graham shot himself by accident. The only proof of his

suicide was contained in the letter to me, and of this letter the public

never heard anything. To the present day Lord Crediton thinks that the

whole thing was accidental.’

‘Cyril Graham sacrificed his life to a great Idea,’ I answered; ‘and if

you will not tell of his martyrdom, tell at least of his faith.’

‘His faith,’ said Erskine, ‘was fixed in a thing that was false, in a

thing that was unsound, in a thing that no Shakespearean scholar would

accept for a moment. The theory would be laughed at. Don’t make a fool

of yourself, and don’t follow a trail that leads nowhere. You start by

assuming the existence of the very person whose existence is the thing to

be proved.

Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.

They were elements of his nature to which he gave

visible form, impulses that stirred so strongly within him that he had,

as it were perforce, to suffer them to realise their energy, not on the

lower plane of actual life, where they would have been trammelled and

constrained and so made imperfect, but on that imaginative plane of art

where Love can indeed find in Death its rich fulfilment, where one can

stab the eavesdropper behind the arras, and wrestle in a new-made grave,

and make a guilty king drink his own hurt, and see one’s father’s spirit,

beneath the glimpses of the moon, stalking in complete steel from misty

wall to wall. Action being limited would have left Shakespeare

unsatisfied and unexpressed; and, just as it is because he did nothing

that he has been able to achieve everything, so it is because he never

speaks to us of himself in his plays that his plays reveal him to us

absolutely, and show us his true nature and temperament far more

completely than do those strange and exquisite sonnets, even, in which he

bares to crystal eyes the secret closet of his heart. Yes, the objective

form is the most subjective in matter. Man is least himself when he

talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the

truth.

ERNEST. The critic, then, being limited to the subjective form, will

necessarily be less able fully to express himself than the artist, who

has always at his disposal the forms that are impersonal and objective.

GILBERT. Not necessarily, and certainly not at all if he recognises that

each mode of criticism is, in its highest development, simply a mood, and

that we are never more true to ourselves than when we are inconsistent.

The æsthetic critic, constant only to the principle of beauty in all

things, will ever be looking for fresh impressions, winning from the

various schools the secret of their charm, bowing, it may be, before

foreign altars, or smiling, if it be his fancy, at strange new gods.

What other people call one’s past has, no doubt, everything to do with

them, but has absolutely nothing to do with oneself. The man who regards

his past is a man who deserves to have no future to look forward to.

When one has found expression for a mood, one has done with it.

We live in an age when unnecessary things are our only necessities.

Finally his bell sounded, and

Victor came in softly with a cup of tea, and a pile of letters, on a

small tray of old Sevres china, and drew back the olive-satin curtains,

with their shimmering blue lining, that hung in front of the three tall

windows.

“Monsieur has well slept this morning,” he said, smiling.

“What o’clock is it, Victor?” asked Dorian Gray drowsily.

“One hour and a quarter, Monsieur.”

How late it was! He sat up, and having sipped some tea, turned over his

letters. One of them was from Lord Henry, and had been brought by hand

that morning. He hesitated for a moment, and then put it aside. The

others he opened listlessly. They contained the usual collection of

cards, invitations to dinner, tickets for private views, programmes of

charity concerts, and the like that are showered on fashionable young

men every morning during the season. There was a rather heavy bill for

a chased silver Louis-Quinze toilet-set that he had not yet had the

courage to send on to his guardians, who were extremely old-fashioned

people and did not realize that we live in an age when unnecessary

things are our only necessities; and there were several very

courteously worded communications from Jermyn Street money-lenders

offering to advance any sum of money at a moment’s notice and at the

most reasonable rates of interest.

After about ten minutes he got up, and throwing on an elaborate

dressing-gown of silk-embroidered cashmere wool, passed into the

onyx-paved bathroom. The cool water refreshed him after his long sleep.

He seemed to have forgotten all that he had gone through. A dim sense

of having taken part in some strange tragedy came to him once or twice,

but there was the unreality of a dream about it.

As soon as he was dressed, he went into the library and sat down to a

light French breakfast that had been laid out for him on a small round

table close to the open window. It was an exquisite day. The warm air

seemed laden with spices. A bee flew in and buzzed round the

blue-dragon bowl that, filled with sulphur-yellow roses, stood before

him. He felt perfectly happy.

Suddenly his eye fell on the screen that he had placed in front of the

portrait, and he started.

One should never trust a woman who tells one her real age. A woman who would tell one that would tell one anything.

I hope I shall make a

good secretary.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. You will be the pattern secretary, Gerald. [_Talks to

him_.]

MRS. ALLONBY. You enjoy country life, Miss Worsley?

HESTER. Very much indeed.

MRS. ALLONBY. Don’t find yourself longing for a London dinner-party?

HESTER. I dislike London dinner-parties.

MRS. ALLONBY. I adore them. The clever people never listen, and the

stupid people never talk.

HESTER. I think the stupid people talk a great deal.

MRS. ALLONBY. Ah, I never listen!

LORD ILLINGWORTH. My dear boy, if I didn’t like you I wouldn’t have made

you the offer. It is because I like you so much that I want to have you

with me.

[_Exit_ HESTER _with_ GERALD.]

Charming fellow, Gerald Arbuthnot!

MRS. ALLONBY. He is very nice; very nice indeed. But I can’t stand the

American young lady.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Why?

MRS. ALLONBY. She told me yesterday, and in quite a loud voice too, that

she was only eighteen. It was most annoying.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. One should never trust a woman who tells one her real

age. A woman who would tell one that, would tell one anything.

MRS. ALLONBY. She is a Puritan besides—

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Ah, that is inexcusable. I don’t mind plain women

being Puritans. It is the only excuse they have for being plain. But

she is decidedly pretty. I admire her immensely. [_Looks steadfastly

at_ MRS. ALLONBY.]

MRS. ALLONBY. What a thoroughly bad man you must be!

LORD ILLINGWORTH. What do you call a bad man?

MRS. ALLONBY. The sort of man who admires innocence.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. And a bad woman?

MRS. ALLONBY. Oh! the sort of woman a man never gets tired of.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. You are severe—on yourself.

MRS. ALLONBY. Define us as a sex.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Sphinxes without secrets.

MRS. ALLONBY. Does that include the Puritan women?

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Do you know, I don’t believe in the existence of

Puritan women? I don’t think there is a woman in the world who would not

be a little flattered if one made love to her. It is that which makes

women so irresistibly adorable.

MRS.

Even things that are true can be proved.

To reveal art and

conceal the artist is art’s aim. The critic is he who can translate

into another manner or a new material his impression of beautiful

things.

The highest as the lowest form of criticism is a mode of autobiography.

Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without

being charming. This is a fault.

Those who find beautiful meanings in beautiful things are the

cultivated. For these there is hope. They are the elect to whom

beautiful things mean only beauty.

There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well

written, or badly written. That is all.

The nineteenth century dislike of realism is the rage of Caliban seeing

his own face in a glass.

The nineteenth century dislike of romanticism is the rage of Caliban

not seeing his own face in a glass. The moral life of man forms part of

the subject-matter of the artist, but the morality of art consists in

the perfect use of an imperfect medium. No artist desires to prove

anything. Even things that are true can be proved. No artist has

ethical sympathies. An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable

mannerism of style. No artist is ever morbid. The artist can express

everything. Thought and language are to the artist instruments of an

art. Vice and virtue are to the artist materials for an art. From the

point of view of form, the type of all the arts is the art of the

musician. From the point of view of feeling, the actor’s craft is the

type. All art is at once surface and symbol. Those who go beneath the

surface do so at their peril. Those who read the symbol do so at their

peril. It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.

Diversity of opinion about a work of art shows that the work is new,

complex, and vital. When critics disagree, the artist is in accord with

himself. We can forgive a man for making a useful thing as long as he

does not admire it. The only excuse for making a useless thing is that

one admires it intensely.

All art is quite useless.

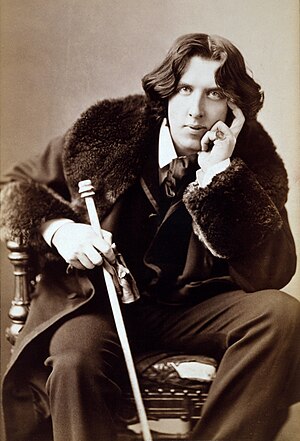

OSCAR WILDE

CHAPTER I.

She wore far too much rouge last night and not quite enough clothes. That is always a sign of despair in a woman.

In defending myself against Mrs. Cheveley, I have a

right to use any weapon I can find, have I not?

LORD GORING. [_Still looking in the glass_.] In your place I don’t

think I should have the smallest scruple in doing so. She is thoroughly

well able to take care of herself.

SIR ROBERT CHILTERN. [_Sits down at the table and takes a pen in his

hand_.] Well, I shall send a cipher telegram to the Embassy at Vienna,

to inquire if there is anything known against her. There may be some

secret scandal she might be afraid of.

LORD GORING. [_Settling his buttonhole_.] Oh, I should fancy Mrs.

Cheveley is one of those very modern women of our time who find a new

scandal as becoming as a new bonnet, and air them both in the Park every

afternoon at five-thirty. I am sure she adores scandals, and that the

sorrow of her life at present is that she can’t manage to have enough of

them.

SIR ROBERT CHILTERN. [_Writing_.] Why do you say that?

LORD GORING. [_Turning round_.] Well, she wore far too much rouge last

night, and not quite enough clothes. That is always a sign of despair in

a woman.

SIR ROBERT CHILTERN. [_Striking a bell_.] But it is worth while my

wiring to Vienna, is it not?

LORD GORING. It is always worth while asking a question, though it is

not always worth while answering one.

[_Enter_ MASON.]

SIR ROBERT CHILTERN. Is Mr. Trafford in his room?

MASON. Yes, Sir Robert.

SIR ROBERT CHILTERN. [_Puts what he has written into an envelope_,

_which he then carefully closes_.] Tell him to have this sent off in

cipher at once. There must not be a moment’s delay.

MASON. Yes, Sir Robert.

SIR ROBERT CHILTERN. Oh! just give that back to me again.

[_Writes something on the envelope_. MASON _then goes out with the

letter_.]

SIR ROBERT CHILTERN. She must have had some curious hold over Baron

Arnheim. I wonder what it was.

LORD GORING. [_Smiling_.] I wonder.

SIR ROBERT CHILTERN. I will fight her to the death, as long as my wife

knows nothing.

LORD GORING. [_Strongly_.] Oh, fight in any case—in any case.

SIR ROBERT CHILTERN.

Women have no appreciation of good looks-at least, good women have not.

Had he gone to his aunt’s, he would have been sure

to have met Lord Goodbody there, and the whole conversation would have

been about the feeding of the poor and the necessity for model

lodging-houses. Each class would have preached the importance of those

virtues, for whose exercise there was no necessity in their own lives.

The rich would have spoken on the value of thrift, and the idle grown

eloquent over the dignity of labour. It was charming to have escaped

all that! As he thought of his aunt, an idea seemed to strike him. He

turned to Hallward and said, “My dear fellow, I have just remembered.”

“Remembered what, Harry?”

“Where I heard the name of Dorian Gray.”

“Where was it?” asked Hallward, with a slight frown.

“Don’t look so angry, Basil. It was at my aunt, Lady Agatha’s. She told

me she had discovered a wonderful young man who was going to help her

in the East End, and that his name was Dorian Gray. I am bound to state

that she never told me he was good-looking. Women have no appreciation

of good looks; at least, good women have not. She said that he was very

earnest and had a beautiful nature. I at once pictured to myself a

creature with spectacles and lank hair, horribly freckled, and tramping

about on huge feet. I wish I had known it was your friend.”

“I am very glad you didn’t, Harry.”

“Why?”

“I don’t want you to meet him.”

“You don’t want me to meet him?”

“No.”

“Mr. Dorian Gray is in the studio, sir,” said the butler, coming into

the garden.

“You must introduce me now,” cried Lord Henry, laughing.

The painter turned to his servant, who stood blinking in the sunlight.

“Ask Mr. Gray to wait, Parker: I shall be in in a few moments.” The man

bowed and went up the walk.

Then he looked at Lord Henry. “Dorian Gray is my dearest friend,” he

said. “He has a simple and a beautiful nature. Your aunt was quite

right in what she said of him. Don’t spoil him. Don’t try to influence

him. Your influence would be bad. The world is wide, and has many

marvellous people in it. Don’t take away from me the one person who

gives to my art whatever charm it possesses: my life as an artist

depends on him.

The public make use of the classics of a country as a means of checking the progress of Art. They degrade the classics into authorities.... A fresh mode of Beauty is absolutely distasteful to them, and whenever it appears they get so angry and bewildered that they always use two stupid expressions--one is that the work of art is grossly unintelligible; the other, that the work of art is grossly immoral. What they mean by these words seems to me to be this. When they say a work is grossly unintelligible, they mean that the artist has said or made a beautiful thing that is new; when they describe a work as grossly immoral, they mean that the artist has said or made a beautiful thing that is true.

Strangely enough, or not strangely, according to

one’s own views, this acceptance of the classics does a great deal of

harm. The uncritical admiration of the Bible and Shakespeare in England

is an instance of what I mean. With regard to the Bible, considerations

of ecclesiastical authority enter into the matter, so that I need not

dwell upon the point.

But in the case of Shakespeare it is quite obvious that the public really

see neither the beauties nor the defects of his plays. If they saw the

beauties, they would not object to the development of the drama; and if

they saw the defects, they would not object to the development of the

drama either. The fact is, the public make use of the classics of a

country as a means of checking the progress of Art. They degrade the

classics into authorities. They use them as bludgeons for preventing the

free expression of Beauty in new forms. They are always asking a writer

why he does not write like somebody else, or a painter why he does not

paint like somebody else, quite oblivious of the fact that if either of

them did anything of the kind he would cease to be an artist. A fresh

mode of Beauty is absolutely distasteful to them, and whenever it appears

they get so angry, and bewildered that they always use two stupid

expressions—one is that the work of art is grossly unintelligible; the

other, that the work of art is grossly immoral. What they mean by these

words seems to me to be this. When they say a work is grossly

unintelligible, they mean that the artist has said or made a beautiful

thing that is new; when they describe a work as grossly immoral, they

mean that the artist has said or made a beautiful thing that is true.

The former expression has reference to style; the latter to

subject-matter. But they probably use the words very vaguely, as an

ordinary mob will use ready-made paving-stones. There is not a single

real poet or prose-writer of this century, for instance, on whom the

British public have not solemnly conferred diplomas of immorality, and

these diplomas practically take the place, with us, of what in France, is

the formal recognition of an Academy of Letters, and fortunately make the

establishment of such an institution quite unnecessary in England. Of

course, the public are very reckless in their use of the word. That they

should have called Wordsworth an immoral poet, was only to be expected.

Wordsworth was a poet. But that they should have called Charles Kingsley

an immoral novelist is extraordinary. Kingsley’s prose was not of a very

fine quality. Still, there is the word, and they use it as best they

can. An artist is, of course, not disturbed by it. The true artist is a

man who believes absolutely in himself, because he is absolutely himself.

Well, the way of paradoxes is the way of truth. To test reality we must see it on the tight rope. When the verities become acrobats, we can judge them.

I assure you that it is an education to visit it.”

“But must we really see Chicago in order to be educated?” asked Mr.

Erskine plaintively. “I don’t feel up to the journey.”

Sir Thomas waved his hand. “Mr. Erskine of Treadley has the world on

his shelves. We practical men like to see things, not to read about

them. The Americans are an extremely interesting people. They are

absolutely reasonable. I think that is their distinguishing

characteristic. Yes, Mr. Erskine, an absolutely reasonable people. I

assure you there is no nonsense about the Americans.”

“How dreadful!” cried Lord Henry. “I can stand brute force, but brute

reason is quite unbearable. There is something unfair about its use. It

is hitting below the intellect.”

“I do not understand you,” said Sir Thomas, growing rather red.

“I do, Lord Henry,” murmured Mr. Erskine, with a smile.

“Paradoxes are all very well in their way....” rejoined the baronet.

“Was that a paradox?” asked Mr. Erskine. “I did not think so. Perhaps

it was. Well, the way of paradoxes is the way of truth. To test reality

we must see it on the tight rope. When the verities become acrobats, we

can judge them.”

“Dear me!” said Lady Agatha, “how you men argue! I am sure I never can

make out what you are talking about. Oh! Harry, I am quite vexed with

you. Why do you try to persuade our nice Mr. Dorian Gray to give up the

East End? I assure you he would be quite invaluable. They would love

his playing.”

“I want him to play to me,” cried Lord Henry, smiling, and he looked

down the table and caught a bright answering glance.

“But they are so unhappy in Whitechapel,” continued Lady Agatha.

“I can sympathize with everything except suffering,” said Lord Henry,

shrugging his shoulders. “I cannot sympathize with that. It is too

ugly, too horrible, too distressing. There is something terribly morbid

in the modern sympathy with pain. One should sympathize with the

colour, the beauty, the joy of life. The less said about life’s sores,

the better.”

“Still, the East End is a very important problem,” remarked Sir Thomas

with a grave shake of the head.

“Quite so,” answered the young lord.

Religion does not help me. The faith that others give to what is unseen, I give to what one can touch, and look at. My gods dwell in temples made with hands; and within the circle of actual experience is my creed made perfect and complete: too complete, it may be, for like many or all of those who have placed their heaven in this earth, I have found in it not merely the beauty of heaven, but the horror of hell also.

But were things different: had I not a friend left in the world; were

there not a single house open to me in pity; had I to accept the wallet

and ragged cloak of sheer penury: as long as I am free from all

resentment, hardness and scorn, I would be able to face the life with

much more calm and confidence than I would were my body in purple and

fine linen, and the soul within me sick with hate.

And I really shall have no difficulty. When you really want love you

will find it waiting for you.

I need not say that my task does not end there. It would be

comparatively easy if it did. There is much more before me. I have

hills far steeper to climb, valleys much darker to pass through. And I

have to get it all out of myself. Neither religion, morality, nor reason

can help me at all.

Morality does not help me. I am a born antinomian. I am one of those

who are made for exceptions, not for laws. But while I see that there is

nothing wrong in what one does, I see that there is something wrong in

what one becomes. It is well to have learned that.

Religion does not help me. The faith that others give to what is unseen,

I give to what one can touch, and look at. My gods dwell in temples made

with hands; and within the circle of actual experience is my creed made

perfect and complete: too complete, it may be, for like many or all of

those who have placed their heaven in this earth, I have found in it not

merely the beauty of heaven, but the horror of hell also. When I think

about religion at all, I feel as if I would like to found an order for

those who _cannot_ believe: the Confraternity of the Faithless, one might

call it, where on an altar, on which no taper burned, a priest, in whose

heart peace had no dwelling, might celebrate with unblessed bread and a

chalice empty of wine. Every thing to be true must become a religion.

And agnosticism should have its ritual no less than faith. It has sown

its martyrs, it should reap its saints, and praise God daily for having

hidden Himself from man. But whether it be faith or agnosticism, it must

be nothing external to me. Its symbols must be of my own creating. Only

that is spiritual which makes its own form. If I may not find its secret

within myself, I shall never find it: if I have not got it already, it

will never come to me.

Reason does not help me. It tells me that the laws under which I am

convicted are wrong and unjust laws, and the system under which I have

suffered a wrong and unjust system.

Every single human being should be the fulfilment of a prophecy: for every human being should be the realisation of some ideal, either in the mind of God or in the mind of man.

The two most deeply

suggestive figures of Greek Mythology were, for religion, Demeter, an

Earth Goddess, not one of the Olympians, and for art, Dionysus, the son

of a mortal woman to whom the moment of his birth had proved also the

moment of her death.

But Life itself from its lowliest and most humble sphere produced one far

more marvellous than the mother of Proserpina or the son of Semele. Out

of the Carpenter's shop at Nazareth had come a personality infinitely

greater than any made by myth and legend, and one, strangely enough,

destined to reveal to the world the mystical meaning of wine and the real

beauties of the lilies of the field as none, either on Cithaeron or at

Enna, had ever done.

The song of Isaiah, 'He is despised and rejected of men, a man of sorrows

and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him,' had

seemed to him to prefigure himself, and in him the prophecy was

fulfilled. We must not be afraid of such a phrase. Every single work of

art is the fulfilment of a prophecy: for every work of art is the

conversion of an idea into an image. Every single human being should be

the fulfilment of a prophecy: for every human being should be the

realisation of some ideal, either in the mind of God or in the mind of

man. Christ found the type and fixed it, and the dream of a Virgilian

poet, either at Jerusalem or at Babylon, became in the long progress of

the centuries incarnate in him for whom the world was waiting.

To me one of the things in history the most to be regretted is that the

Christ's own renaissance, which has produced the Cathedral at Chartres,

the Arthurian cycle of legends, the life of St. Francis of Assisi, the

art of Giotto, and Dante's _Divine Comedy_, was not allowed to develop on

its own lines, but was interrupted and spoiled by the dreary classical

Renaissance that gave us Petrarch, and Raphael's frescoes, and Palladian

architecture, and formal French tragedy, and St. Paul's Cathedral, and

Pope's poetry, and everything that is made from without and by dead

rules, and does not spring from within through some spirit informing it.

But wherever there is a romantic movement in art there somehow, and under

some form, is Christ, or the soul of Christ. He is in _Romeo and

Juliet_, in the _Winter's Tale_, in Provencal poetry, in the _Ancient

Mariner_, in _La Belle Dame sans merci_, and in Chatterton's _Ballad of

Charity_.

Nobody is worthy to be loved. The fact that God loves man shows us that in the divine order of ideal things it is written that eternal love is to be given to what is eternally unworthy. Or if that phrase seems to be a bitter one to bear, let us say that everybody is worthy of love, except him who thinks he is.

To me it is so much so that at the close of

each meal I carefully eat whatever crumbs may be left on my tin plate, or

have fallen on the rough towel that one uses as a cloth so as not to soil

one's table; and I do so not from hunger--I get now quite sufficient

food--but simply in order that nothing should be wasted of what is given

to me. So one should look on love.

Christ, like all fascinating personalities, had the power of not merely

saying beautiful things himself, but of making other people say beautiful

things to him; and I love the story St. Mark tells us about the Greek

woman, who, when as a trial of her faith he said to her that he could not

give her the bread of the children of Israel, answered him that the

little dogs--([Greek text], 'little dogs' it should be rendered)--who are

under the table eat of the crumbs that the children let fall. Most

people live for love and admiration. But it is by love and admiration

that we should live. If any love is shown us we should recognise that we

are quite unworthy of it. Nobody is worthy to be loved. The fact that

God loves man shows us that in the divine order of ideal things it is

written that eternal love is to be given to what is eternally unworthy.

Or if that phrase seems to be a bitter one to bear, let us say that every

one is worthy of love, except him who thinks that he is. Love is a

sacrament that should be taken kneeling, and _Domine, non sum dignus_

should be on the lips and in the hearts of those who receive it.

If ever I write again, in the sense of producing artistic work, there are

just two subjects on which and through which I desire to express myself:

one is 'Christ as the precursor of the romantic movement in life': the

other is 'The artistic life considered in its relation to conduct.' The

first is, of course, intensely fascinating, for I see in Christ not

merely the essentials of the supreme romantic type, but all the

accidents, the wilfulnesses even, of the romantic temperament also. He

was the first person who ever said to people that they should live

'flower-like lives.' He fixed the phrase. He took children as the type

of what people should try to become. He held them up as examples to

their elders, which I myself have always thought the chief use of

children, if what is perfect should have a use. Dante describes the soul

of a man as coming from the hand of God 'weeping and laughing like a

little child,' and Christ also saw that the soul of each one should be _a

guisa di fanciulla che piangendo e ridendo pargoleggia_.

Nowadays most people die of a sort of creeping common sense, and discover when it is too late that the only things one never regrets are ones mistakes.

“I have always

felt rather guilty when I came to see your dear aunt, for I take no

interest at all in the East End. For the future I shall be able to look

her in the face without a blush.”

“A blush is very becoming, Duchess,” remarked Lord Henry.

“Only when one is young,” she answered. “When an old woman like myself

blushes, it is a very bad sign. Ah! Lord Henry, I wish you would tell

me how to become young again.”

He thought for a moment. “Can you remember any great error that you

committed in your early days, Duchess?” he asked, looking at her across

the table.

“A great many, I fear,” she cried.

“Then commit them over again,” he said gravely. “To get back one’s

youth, one has merely to repeat one’s follies.”

“A delightful theory!” she exclaimed. “I must put it into practice.”

“A dangerous theory!” came from Sir Thomas’s tight lips. Lady Agatha

shook her head, but could not help being amused. Mr. Erskine listened.

“Yes,” he continued, “that is one of the great secrets of life.

Nowadays most people die of a sort of creeping common sense, and

discover when it is too late that the only things one never regrets are

one’s mistakes.”

A laugh ran round the table.

He played with the idea and grew wilful; tossed it into the air and

transformed it; let it escape and recaptured it; made it iridescent

with fancy and winged it with paradox. The praise of folly, as he went

on, soared into a philosophy, and philosophy herself became young, and

catching the mad music of pleasure, wearing, one might fancy, her

wine-stained robe and wreath of ivy, danced like a Bacchante over the

hills of life, and mocked the slow Silenus for being sober. Facts fled

before her like frightened forest things. Her white feet trod the huge

press at which wise Omar sits, till the seething grape-juice rose round

her bare limbs in waves of purple bubbles, or crawled in red foam over

the vat’s black, dripping, sloping sides. It was an extraordinary

improvisation. He felt that the eyes of Dorian Gray were fixed on him,

and the consciousness that amongst his audience there was one whose

temperament he wished to fascinate seemed to give his wit keenness and

to lend colour to his imagination.

The public have an insatiable curiosity to know everything, except what is worth knowing.

That was true at the time, no doubt. But at the present moment

it really is the only estate. It has eaten up the other three. The

Lords Temporal say nothing, the Lords Spiritual have nothing to say, and

the House of Commons has nothing to say and says it. We are dominated by

Journalism. In America the President reigns for four years, and

Journalism governs for ever and ever. Fortunately in America Journalism

has carried its authority to the grossest and most brutal extreme. As a

natural consequence it has begun to create a spirit of revolt. People

are amused by it, or disgusted by it, according to their temperaments.

But it is no longer the real force it was. It is not seriously treated.

In England, Journalism, not, except in a few well-known instances, having

been carried to such excesses of brutality, is still a great factor, a

really remarkable power. The tyranny that it proposes to exercise over

people’s private lives seems to me to be quite extraordinary. The fact

is, that the public have an insatiable curiosity to know everything,

except what is worth knowing. Journalism, conscious of this, and having

tradesman-like habits, supplies their demands. In centuries before ours

the public nailed the ears of journalists to the pump. That was quite

hideous. In this century journalists have nailed their own ears to the

keyhole. That is much worse. And what aggravates the mischief is that

the journalists who are most to blame are not the amusing journalists who

write for what are called Society papers. The harm is done by the

serious, thoughtful, earnest journalists, who solemnly, as they are doing

at present, will drag before the eyes of the public some incident in the

private life of a great statesman, of a man who is a leader of political

thought as he is a creator of political force, and invite the public to

discuss the incident, to exercise authority in the matter, to give their

views, and not merely to give their views, but to carry them into action,

to dictate to the man upon all other points, to dictate to his party, to

dictate to his country; in fact, to make themselves ridiculous,

offensive, and harmful.

But then one regrets the loss even of ones worst habits. Perhaps one regrets them the most. They are such an essential part of ones personality.

It must be a delightful

city, and possess all the attractions of the next world.”

“What do you think has happened to Basil?” asked Dorian, holding up his

Burgundy against the light and wondering how it was that he could

discuss the matter so calmly.

“I have not the slightest idea. If Basil chooses to hide himself, it is

no business of mine. If he is dead, I don’t want to think about him.

Death is the only thing that ever terrifies me. I hate it.”

“Why?” said the younger man wearily.

“Because,” said Lord Henry, passing beneath his nostrils the gilt

trellis of an open vinaigrette box, “one can survive everything

nowadays except that. Death and vulgarity are the only two facts in the

nineteenth century that one cannot explain away. Let us have our coffee

in the music-room, Dorian. You must play Chopin to me. The man with

whom my wife ran away played Chopin exquisitely. Poor Victoria! I was

very fond of her. The house is rather lonely without her. Of course,

married life is merely a habit, a bad habit. But then one regrets the

loss even of one’s worst habits. Perhaps one regrets them the most.

They are such an essential part of one’s personality.”

Dorian said nothing, but rose from the table, and passing into the next

room, sat down to the piano and let his fingers stray across the white

and black ivory of the keys. After the coffee had been brought in, he

stopped, and looking over at Lord Henry, said, “Harry, did it ever

occur to you that Basil was murdered?”

Lord Henry yawned. “Basil was very popular, and always wore a Waterbury

watch. Why should he have been murdered? He was not clever enough to

have enemies. Of course, he had a wonderful genius for painting. But a

man can paint like Velasquez and yet be as dull as possible. Basil was

really rather dull. He only interested me once, and that was when he

told me, years ago, that he had a wild adoration for you and that you

were the dominant motive of his art.”

“I was very fond of Basil,” said Dorian with a note of sadness in his

voice. “But don’t people say that he was murdered?”

“Oh, some of the papers do. It does not seem to me to be at all

probable.

In examinations the foolish ask questions that the wise cannot answer.

In

all important matters, style, not sincerity, is the essential.

If one tells the truth one is sure, sooner or later, to be found out.

Pleasure is the only thing one should live for. Nothing ages like

happiness.

It is only by not paying one’s bills that one can hope to live in the

memory of the commercial classes.

No crime is vulgar, but all vulgarity is crime. Vulgarity is the conduct

of others.

Only the shallow know themselves.

Time is waste of money.

One should always be a little improbable.

There is a fatality about all good resolutions. They are invariably made

too soon.

The only way to atone for being occasionally a little overdressed is by

being always absolutely overeducated.

To be premature is to be perfect.

Any preoccupation with ideas of what is right or wrong in conduct shows

an arrested intellectual development.

Ambition is the last refuge of the failure.

A truth ceases to be true when more than one person believes in it.

In examinations the foolish ask questions that the wise cannot answer.

Greek dress was in its essence inartistic. Nothing should reveal the

body but the body.

One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.

It is only the superficial qualities that last. Man’s deeper nature is

soon found out.

Industry is the root of all ugliness.

The ages live in history through their anachronisms.

It is only the gods who taste of death. Apollo has passed away, but

Hyacinth, whom men say he slew, lives on. Nero and Narcissus are always

with us.

The old believe everything: the middle-aged suspect everything; the young

know everything.

The condition of perfection is idleness: the aim of perfection is youth.

Only the great masters of style ever succeeded in being obscure.

There is something tragic about the enormous number of young men there

are in England at the present moment who start life with perfect

profiles, and end by adopting some useful profession.

To love oneself is the beginning of a life-long romance.

MRS.

“Ordinary riches can be stolen, real riches cannot. In your soul are infinitely precious things that cannot be taken from you.”