“True science teaches, above all, to doubt and to be ignorant”

It is advocacy, or what amounts to the same thing, theology,

that teaches the distrust of reason--not true science, not the science

of investigation, sceptical in the primitive and direct meaning of the

word, which hastens towards no predetermined solution nor proceeds save

by the testing of hypotheses.

Take the _Summa Theologica_ of St. Thomas, the classical monument of the

theology--that is, of the advocacy--of Catholicism, and open it where

you please. First comes the thesis--_utrum_ ... whether such a thing be

thus or otherwise; then the objections--_ad primum sic proceditur_; next

the answers to these objections--_sed contra est_ ... or _respondeo

dicendum_.... Pure advocacy! And underlying many, perhaps most, of its

arguments you will find a logical fallacy which may be expressed _more

scholastico_ by this syllogism: I do not understand this fact save by

giving it this explanation; it is thus that I must understand it,

therefore this must be its explanation. The alternative being that I am

left without any understanding of it at all. True science teaches, above

all, to doubt and to be ignorant; advocacy neither doubts nor believes

that it does not know. It requires a solution.

To the mentality that assumes, more or less consciously, that we must of

necessity find a solution to every problem, belongs the argument based

on the disastrous consequences of a thing. Take any book of

apologetics--that is to say, of theological advocacy--and you will see

how many times you will meet with this phrase--"the disastrous

consequences of this doctrine." Now the disastrous consequences of a

doctrine prove at most that the doctrine is disastrous, but not that it

is false, for there is no proof that the true is necessarily that which

suits us best. The identification of the true and the good is but a

pious wish. In his _Études sur Blaise Pascal_, A. Vinet says: "Of the

two needs that unceasingly belabour human nature, that of happiness is

not only the more universally felt and the more constantly experienced,

but it is also the more imperious. And this need is not only of the

senses; it is intellectual.

“Suffering is the substance of life and the root of personality, for it is only suffering that makes us persons.”

Whosoever knows not the Son will never know the Father, and the Father

is only known through the Son; whosoever knows not the Son of Man--he

who suffers bloody anguish and the pangs of a breaking heart, whose soul

is heavy within him even unto death, who suffers the pain that kills and

brings to life again--will never know the Father, and can know nothing

of the suffering God.

He who does not suffer, and who does not suffer because he does not

live, is that logical and frozen _ens realissimum_, the _primum movens_,

that impassive entity, which because of its impassivity is nothing but a

pure idea. The category does not suffer, but neither does it live or

exist as a person. And how is the world to derive its origin and life

from an impassive idea? Such a world would be but the idea of the world.

But the world suffers, and suffering is the sense of the flesh of

reality; it is the spirit's sense of its mass and substance; it is the

self's sense of its own tangibility; it is immediate reality.

Suffering is the substance of life and the root of personality, for it

is only suffering that makes us persons. And suffering is universal,

suffering is that which unites all us living beings together; it is the

universal or divine blood that flows through us all. That which we call

will, what is it but suffering?

And suffering has its degrees, according to the depth of its

penetration, from the suffering that floats upon the sea of appearances

to the eternal anguish, the source of the tragic sense of life, which

seeks a habitation in the depths of the eternal and there awakens

consolation; from the physical suffering that contorts our bodies to the

religious anguish that flings us upon the bosom of God, there to be

watered by the divine tears.

Anguish is something far deeper, more intimate, and more spiritual than

suffering. We are wont to feel the touch of anguish even in the midst of

that which we call happiness, and even because of this happiness itself,

to which we cannot resign ourselves and before which we tremble. The

happy who resign themselves to their apparent happiness, to a transitory

happiness, seem to be as men without substance, or, at any rate, men who

have not discovered this substance in themselves, who have not touched

it.

“Love is the child of illusion and the parent of disillusion.”

See Troeltsch, _Systematische christliche Religion_, in _Die Kultur

der Gegenwart_ series.

[32] _Die Analyse der Empfindigungen und das Verhältniss des Physischen

zum Psychischen_, i., § 12, note.

[33] I have left the original expression here, almost without

translating it--_Existents-Consequents_. It means the existential or

practical, not the purely rational or logical, consequence. (Author's

note.)

[34] Albrecht Ritschl: _Geschichte des Pietismus_, ii., Abt. i., Bonn,

1884, p. 251.

[35] Thou art the cause of my suffering, O non-existing God, for if Thou

didst exist, then should I also really exist.

VII

LOVE, SUFFERING, PITY, AND PERSONALITY

CAIN: Let me, or happy or unhappy, learn

To anticipate my immortality.

LUCIFER: Thou didst before I came upon thee.

CAIN: How?

LUCIFER: By suffering.

BYRON: _Cain_, Act II., Scene I.

The most tragic thing in the world and in life, readers and brothers of

mine, is love. Love is the child of illusion and the parent of

disillusion; love is consolation in desolation; it is the sole medicine

against death, for it is death's brother.

_Fratelli, a un tempo stesso, Amore e Morte

Ingeneró la sorte_,

as Leopardi sang.

Love seeks with fury, through the medium of the beloved, something

beyond, and since it finds it not, it despairs.

Whenever we speak of love there is always present in our memory the idea

of sexual love, the love between man and woman, whose end is the

perpetuation of the human race upon the earth. Hence it is that we never

succeed in reducing love either to a purely intellectual or to a purely

volitional element, putting aside that part in it which belongs to the

feeling, or, if you like, to the senses. For, in its essence, love is

neither idea nor volition; rather it is desire, feeling; it is something

carnal in spirit itself. Thanks to love, we feel all that spirit has of

flesh in it.

Sexual love is the generative type of every other love. In love and by

love we seek to perpetuate ourselves, and we perpetuate ourselves on the

earth only on condition that we die, that we yield up our life to

others.

“What we believe to be the motives of our conduct are usually but the pretexts for it.”

And this leaves us as we were before. For it is precisely

this inner contradiction that unifies my life and gives it its practical

purpose.

Or rather it is the conflict itself, it is this self-same passionate

uncertainty, that unifies my action and makes me live and work.

We think in order that we may live, I have said; but perhaps it were

more correct to say that we think because we live, and the form of our

thought corresponds with that of our life. Once more I must repeat that

our ethical and philosophical doctrines in general are usually merely

the justification _a posteriori_ of our conduct, of our actions. Our

doctrines are usually the means we seek in order to explain and justify

to others and to ourselves our own mode of action. And this, be it

observed, not merely for others, but for ourselves. The man who does not

really know why he acts as he does and not otherwise, feels the

necessity of explaining to himself the motive of his action and so he

forges a motive. What we believe to be the motives of our conduct are

usually but the pretexts for it. The very same reason which one man may

regard as a motive for taking care to prolong his life may be regarded

by another man as a motive for shooting himself.

Nevertheless it cannot be denied that reasons, ideas, have an influence

upon human actions, and sometimes even determine them, by a process

analogous to that of suggestion upon a hypnotized person, and this is so

because of the tendency in every idea to resolve itself into action--an

idea being simply an inchoate or abortive act. It was this notion that

suggested to Fouillée his theory of idea-forces. But ordinarily ideas

are forces which we accommodate to other forces, deeper and much less

conscious.

But putting all this aside for the present, what I wish to establish is

that uncertainty, doubt, perpetual wrestling with the mystery of our

final destiny, mental despair, and the lack of any solid and stable

dogmatic foundation, may be the basis of an ethic.

He who bases or thinks that he bases his conduct--his inward or his

outward conduct, his feeling or his action--upon a dogma or theoretical

principle which he deems incontrovertible, runs the risk of becoming a

fanatic, and moreover, the moment that this dogma is weakened or

shattered, the morality based upon it gives way.

Only he who attempts the absurd is capable of achieving the impossible.

And then people are

surprised at the triumph of those who have the courage to face ridicule

serenely, of those who rid themselves of the herd-instinct.

In the province of Salamanca there was a remarkable man who rose from

the greatest poverty to be a millionaire. The peasants of the district,

with the sheep-like instincts of their kind, were only able to explain

his success by supposing that in his younger days he had embezzled

money, for these wretched peasants, crusted over with common sense

and entirely lacking in moral courage, believe only in theft and the

lottery. But one day I was told of a quixotic feat which this cattle

farmer had performed. It seems that he had brought sea-bream’s spawn

from the Cantabrian coast to put in one of his ponds! When I heard

that, I understood everything. He who has the courage to face the jeers

which are bound to be provoked by bringing the spawn of a salt-water

fish to put in a pond in Castile, he who does that deserves his fortune.

But it was absurd, you say? And who knows what is absurd and what is

not? And even if it were! Only he who attempts the absurd is capable

of achieving the impossible. There is only one way of hitting the nail

on the head and that is by hammering on the shoe a hundred times. And

there is only one way of achieving a real triumph and that is by

facing ridicule with serenity. And it is because our agriculturists

haven’t the courage to face ridicule that our agriculture languishes in

its present backward condition.

Yes, all our ills spring from moral cowardice, from the individual’s

lack of staunch resolution in affirming his own truth, his own faith,

and defending it. The soul of this people, this flock of somnolent

sheep, is smothered and swathed in falsehood, and their stupidity

proceeds from their very excess of prudence.

It is claimed that there are certain principles that are beyond

discussion and when anyone attempts to criticize them the air rings

with shouts of protest. Not long ago I proposed that we should

demand the abolition of certain of the articles of our law of Public

Instruction, and a pack of poltroons began to bellow that such a course

was inopportune and impertinent, not to mention stronger and more

offensive epithets that were used.

Those who believe that they believe in God, but without passion in their hearts, without anguish in mind, without uncertainty, without doubt, without an element of despair even in their consolation, believe only in the God idea, not God Himself.

Augustine said: "I will seek Thee, Lord, by

calling upon Thee, and I will call upon Thee by believing in Thee. My

faith calls upon Thee, Lord, the faith which Thou hast given me, with

which Thou hast inspired me through the Humanity of Thy Son, through the

ministry of Thy preacher" (_Confessions_, book i., chap. i.). The power

of creating God in our own image and likeness, of personalizing the

Universe, simply means that we carry God within us, as the substance of

what we hope for, and that God is continually creating us in His own

image and likeness.

And we create God--that is to say, God creates Himself in us--by

compassion, by love. To believe in God is to love Him, and in our love

to fear Him; and we begin by loving Him even before knowing Him, and by

loving Him we come at last to see and discover Him in all things.

Those who say that they believe in God and yet neither love nor fear

Him, do not in fact believe in Him but in those who have taught them

that God exists, and these in their turn often enough do not believe in

Him either. Those who believe that they believe in God, but without any

passion in their heart, without anguish of mind, without uncertainty,

without doubt, without an element of despair even in their consolation,

believe only in the God-Idea, not in God Himself. And just as belief in

God is born of love, so also it may be born of fear, and even of hate,

and of such kind was the belief of Vanni Fucci, the thief, whom Dante

depicts insulting God with obscene gestures in Hell (_Inf._, xxv., 1-3).

For the devils also believe in God, and not a few atheists.

Is it not perhaps a mode of believing in God, this fury with which those

deny and even insult Him, who, because they cannot bring themselves to

believe in Him, wish that He may not exist? Like those who believe,

they, too, wish that God may exist; but being men of a weak and passive

or of an evil disposition, in whom reason is stronger than will, they

feel themselves caught in the grip of reason and haled along in their

own despite, and they fall into despair, and because of their despair

they deny, and in their denial they affirm and create the thing that

they deny, and God reveals Himself in them, affirming Himself by their

very denial of Him.

But it will be objected to all this that to demonstrate that faith

creates its own object is to demonstrate that this object is an object

for faith alone, that outside faith it has no objective reality; just

as, on the other hand, to maintain that faith is necessary because it

affords consolation to the masses of the people, or imposes a wholesome

restraint upon them, is to declare that the object of faith is illusory.

“It is sad not to be loved but it is much sadder not to be able to love”

“A lot of good arguments are spoiled by some fool who knows what he is talking about.”

“If a person never contradicts himself, it must be that he says nothing.”

Life is doubt,And faith without doubt is nothing but death.

At times to be silent is to lie. You will win because you have enough brute force. But you will not convince. For to convince you need to persuade. And in order to persuade you would need what you lack: Reason and Right

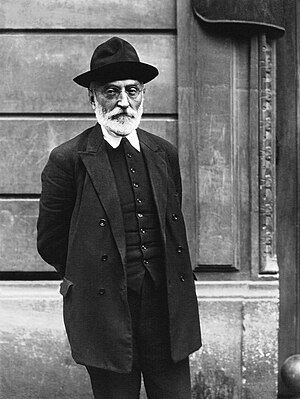

Faith which does not doubt is dead faith. -Miguel de Unamuno, philosopher and writer (1864-1936)

Yes, yes, I see it all! — an enormous social activity, a mighty civilization, a profuseness of science, of art, of industry, of morality, and afterwords, when we have filled the world with industrial marvels, with great factories, with roads, museums and libraries, we shall fall exhausted at the foot of it all, and it will subsist — for whom? Was man made for science or was science made for man?

It is not usually our ideas that make us optimists or pessimists, but it is our optimism or pessimism that makes our ideas.

If it is nothingness that awaits us, let us make an injustice of it, let us fight against destiny, even without hope of victory.

Man is said to be a reasoning animal. I do not know why he has not been defined as an affective or feeling animal. Perhaps that which differentiates him from other animals is feeling rather than reason. More often I have seen a cat reason than laugh or weep. Perhaps it weeps or laughs inwardly — but then perhaps, also inwardly, the crab resolves equations of the second degree.

Sometimes, to remain silent is to lie, since silence can be interpreted as assent.

A pedant who beheld Solon weeping for the death of a son said to him, ‘Why do you weep thus, if weeping avails nothing?’ And the sage answered him, ‘Precisely for that reason—because it does not avail.

Our life is a hope which is continually converting itself into memory and memory in its turn begets hope.

Science says: We must live and seeks the means of prolonging increasing facilitating and amplifying life of making it tolerable and acceptable wisdom says: We must die and seeks how to make us die well.