“Beauty is altogether in the eye of the beholder”

Her beauty bore the marks of

intelligence; her manner was not enough self-contained to be called

courtly; yet it was easy, and carried its own certificate of culture;

it yielded too much to natural affection to deserve the term dignified.

One listening to her, and noticing the variableness of her mood, which

in almost the same instant could pass from gay to serious without ever

reaching an extreme, would pronounce her too timid for achievement

outside the purely domestic; at the same time he would think she

appeared lovable to the last degree, and might be capable of loving in

equal measure.

She was dressed in Byzantine fashion. In crossing the street from her

father's house, she had thrown a veil over her head, but it was now

lying carelessly about her neck. The wooden sandals with blocks under

them, like those yet worn by women in Levantine countries to raise them

out of the dust and mud when abroad, had been shaken lightly from her

feet at the top of the stairs. Perfectly at home, she advanced to the

table, and put one of her bare arms around the old man's neck,

regardless of the white locks it crushed close down, and replied:

"Thou flatterer! Do I not know beauty is altogether in the eye of the

beholder, and that all persons do not see alike? Tell me why, knowing

the work was to be done, you did not send for me to help you? Was it

for nothing you made me acquainted with figures until--I have your

authority for the saying--I might have stood for professor of

mathematics in the best of the Alexandrian schools? Do not shake your

head at me--or"--

With the new idea all alight in her face, she ran around the table, and

caught up one of the diagrams.

"Ah, it is as I thought, father! The work I love best, and can do best!

Whose is the nativity? Not mine, I know; for I was born in the glad

time when Venus ruled the year. Anael, her angel, held his wings over

me against this very wry-faced, snow-chilled Saturn, whom I am so glad

to see in the Seventh House, which is the House of Woe. Whose the

nativity, I say?"

"Nay, child--pretty child, and wilful--you have a trick of getting my

secrets from me. I sometimes think I am in thy hands no more than

tawdry lace just washed and being wrung preparatory to hanging in the

air from thy lattice.

“When people are lonely they stoop to any companionship.”

Vegetation entirely ceased. The sand, so crusted on the surface that it

broke into rattling flakes at every step, held undisputed sway. The

Jebel was out of view, and there was no landmark visible. The shadow

that before followed had now shifted to the north, and was keeping even

race with the objects which cast it; and as there was no sign of

halting, the conduct of the traveller became each moment more strange.

No one, be it remembered, seeks the desert for a pleasure-ground. Life

and business traverse it by paths along which the bones of things dead

are strewn as so many blazons. Such are the roads from well to well,

from pasture to pasture. The heart of the most veteran sheik beats

quicker when he finds himself alone in the pathless tracts. So the man

with whom we are dealing could not have been in search of pleasure;

neither was his manner that of a fugitive; not once did he look behind

him. In such situations fear and curiosity are the most common

sensations; he was not moved by them. When men are lonely, they stoop

to any companionship; the dog becomes a comrade, the horse a friend,

and it is no shame to shower them with caresses and speeches of love.

The camel received no such token, not a touch, not a word.

Exactly at noon the dromedary, of its own will, stopped, and uttered

the cry or moan, peculiarly piteous, by which its kind always protest

against an overload, and sometimes crave attention and rest. The master

thereupon bestirred himself, waking, as it were, from sleep. He threw

the curtains of the _houdah_ up, looked at the sun, surveyed the

country on every side long and carefully, as if to identify an

appointed place. Satisfied with the inspection, he drew a deep breath

and nodded, much as to say, “At last, at last!” A moment after, he

crossed his hands upon his breast, bowed his head, and prayed silently.

The pious duty done, he prepared to dismount. From his throat proceeded

the sound heard doubtless by the favorite camels of Job—_Ikh! ikh!_—the

signal to kneel. Slowly the animal obeyed, grunting the while.

“As a rule, there is no surer way to the dislike of men than to behave well where they have behaved badly”

Presently she

received the water; her father drank; then she raised the cup to her

lips, and, leaning down, gave it to Ben-Hur; never action more graceful

and gracious.

“Keep it, we pray of thee! It is full of blessings—all thine!”

Immediately the camel was aroused, and on his feet, and about to go,

when the old man called,

“Stand thou here.”

Ben-Hur went to him respectfully.

“Thou hast served the stranger well to-day. There is but one God. In

his holy name I thank thee. I am Balthasar, the Egyptian. In the Great

Orchard of Palms, beyond the village of Daphne, in the shade of the

palms, Sheik Ilderim the Generous abideth in his tents, and we are his

guests. Seek us there. Thou shalt have welcome sweet with the savor of

the grateful.”

Ben-Hur was left in wonder at the old man’s clear voice and reverend

manner. As he gazed after the two departing, he caught sight of Messala

going as he had come, joyous, indifferent, and with a mocking laugh.

CHAPTER IX

As a rule, there is no surer way to the dislike of men than to behave

well where they have behaved badly. In this instance, happily, Malluch

was an exception to the rule. The affair he had just witnessed raised

Ben-Hur in his estimation, since he could not deny him courage and

address; could he now get some insight into the young man’s history,

the results of the day would not be all unprofitable to good master

Simonides.

On the latter point, referring to what he had as yet learned, two facts

comprehended it all—the subject of his investigation was a Jew, and the

adopted son of a famous Roman. Another conclusion which might be of

importance was beginning to formulate itself in the shrewd mind of the

emissary; between Messala and the son of the duumvir there was a

connection of some kind. But what was it?—and how could it be reduced

to assurance? With all his sounding, the ways and means of solution

were not at call. In the heat of the perplexity, Ben-Hur himself came

to his help. He laid his hand on Malluch’s arm and drew him out of the

crowd, which was already going back to its interest in the gray old

priest and the mystic fountain.

“One is never more on trial than in the moment of excessive good fortune.”

”

From separate sheets he then read footings, which, fractions omitted,

were as follows:

By ships 60 talents ” goods in store 110 ” ” cargoes in

transit 75 ” ” camels, horses, etc. 20 ” ” warehouses 10

” ” bills due 54 ” ” money on hand and subject to draft 224 ”

—— Total 553 ”

“To these now, to the five hundred and fifty-three talents gained, add

the original capital I had from thy father, and thou hast SIX HUNDRED

AND SEVENTY THREE TALENTS!—and all thine—making thee, O son of Hur, the

richest subject in the world.”

He took the papyri from Esther, and, reserving one, rolled them and

offered them to Ben-Hur. The pride perceptible in his manner was not

offensive; it might have been from a sense of duty well done; it might

have been for Ben-Hur without reference to himself.

“And there is nothing,” he added, dropping his voice, but not his

eyes—“there is nothing now thou mayst not do.”

The moment was one of absorbing interest to all present. Simonides

crossed his hands upon his breast again; Esther was anxious; Ilderim

nervous. A man is never so on trial as in the moment of excessive

good-fortune.

Taking the roll, Ben-Hur arose, struggling with emotion.

“All this is to me as a light from heaven, sent to drive away a night

which has been so long I feared it would never end, and so dark I had

lost the hope of seeing,” he said, with a husky voice. “I give first

thanks to the Lord, who has not abandoned me, and my next to thee, O

Simonides. Thy faithfulness outweighs the cruelty of others, and

redeems our human nature. ‘There is nothing I cannot do:’ be it so.

Shall any man in this my hour of such mighty privilege be more generous

than I? Serve me as a witness now, Sheik Ilderim. Hear thou my words as

I shall speak them—hear and remember. And thou, Esther, good angel of

this good man! hear thou also.”

He stretched his hand with the roll to Simonides.

“The things these papers take into account—all of them: ships, houses,

goods, camels, horses, money; the least as well as the greatest—give I

back to thee, O Simonides, making them all thine, and sealing them to

thee and thine forever.

“The monuments of the nations are all protests against nothingness after death; so are statues and inscriptions; so is history”

“Let me try, O son of Hur,” he said, directly, “and help you to a clear

understanding of my belief; then it may be, seeing how the spiritual

kingdom I expect him to set up can be more excellent in every sense

than anything of mere Cæsarean splendor, you will better understand

the reason of the interest I take in the mysterious person we are going

to welcome.

“I cannot tell you when the idea of a Soul in every man had its origin.

Most likely the first parents brought it with them out of the garden in

which they had their first dwelling. We all do know, however, that it

has never perished entirely out of mind. By some peoples it was lost,

but not by all; in some ages it dulled and faded, in others it was

overwhelmed with doubts; but, in great goodness, God kept sending us at

intervals mighty intellects to argue it back to faith and hope.

“Why should there be a Soul in every man? Look, O son of Hur—for one

moment look at the necessity of such a device. To lie down and die, and

be no more—no more forever—time never was when man wished for such an

end; nor has the man ever been who did not in his heart promise himself

something better. The monuments of the nations are all protests against

nothingness after death; so are statues and inscriptions; so is

history. The greatest of our Egyptian kings had his effigy cut-out of a

hill of solid rock. Day after day he went with a host in chariots to

see the work; at last it was finished, never effigy so grand, so

enduring: it looked like him—the features were his, faithful even in

expression. Now may we not think of him saying in that moment of pride,

‘Let Death come; there is an after-life for me!’ He had his wish. The

statue is there yet.

“But what is the after-life he thus secured? Only a recollection by

men—a glory unsubstantial as moonshine on the brow of the great bust; a

story in stone—nothing more. Meantime what has become of the king?

There is an embalmed body up in the royal tombs which once was his—an

effigy not so fair to look at as the other out in the Desert. But

where, O son of Hur, where is the king himself? Is he fallen into

nothingness? Two thousand years have gone since he was a man alive as

you and I are. Was his last breath the end of him?

“To say yes would be to accuse God; let us rather accept his better

plan of attaining life after death for us—actual life, I mean—the

something more than a place in mortal memory; life with going and

coming, with sensation, with knowledge, with power and all

appreciation; life eternal in term though it may be with changes of

condition.

“I know what I should love to do--to build a study; to write, and to think of nothing else. I want to bury myself in a den of books. I want to saturate myself with the elements of which they are made, and breathe their atmosphere until I am of it. Not a bookworm, being which is to give off no utterances; but a man in the world of writing--one with a pen that shall stop men to listen to it, whether they wish to or not.”

“Am I going home to idleness? No, no. My feet and hands may be still, not so the mind--that has its aspirations yet, and it will work, for it has a law unto itself. Idleness is one thing, doing is another.”

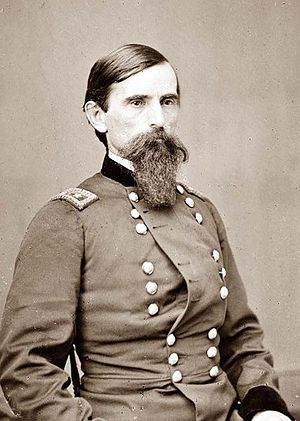

“He met me with politeness and dignity, ... Turning to the officers at the table, he remarked: General Wallace, it is not necessary to introduce you to these gentlemen; you are acquainted with them all.”

“[Wallace shook hands with the Rebel brass.] I was then invited to breakfast, which consisted of corn bread and coffee, the best the gallant officer had in his kitchen, ... We sat at the table about an hour and a half.”

Knowledge leaves no room for chances.

The monuments of the nations are all protests against nothingness after death so are statues and inscriptions so is history.

The monuments of the nations are all protests against nothingness after death so are statues and inscriptions so is history.

Beauty is altogether in the eye of the beholder.

“The happiness of love is in action; its test is what one is willing to do for others.”

“I would have had to kill him, and Death, you know, keeps secrets better even than a guilty Roman.”