“There are certain queer times and occasions in this strange mixed affair we call life when a man takes his whole universe for a vast practical joke”

Suddenly Queequeg started to his feet, hollowing his hand to his ear.

We all heard a faint creaking, as of ropes and yards hitherto muffled

by the storm. The sound came nearer and nearer; the thick mists were

dimly parted by a huge, vague form. Affrighted, we all sprang into the

sea as the ship at last loomed into view, bearing right down upon us

within a distance of not much more than its length.

Floating on the waves we saw the abandoned boat, as for one instant it

tossed and gaped beneath the ship's bows like a chip at the base of a

cataract; and then the vast hull rolled over it, and it was seen no

more till it came up weltering astern. Again we swam for it, were

dashed against it by the seas, and were at last taken up and safely

landed on board. Ere the squall came close to, the other boats had cut

loose from their fish and returned to the ship in good time. The ship

had given us up, but was still cruising, if haply it might light upon

some token of our perishing,— an oar or a lance pole.

CHAPTER 49

The Hyena

There are certain queer times and occasions in this strange mixed

affair we call life when a man takes this whole universe for a vast

practical joke, though the wit thereof he but dimly discerns, and more

than suspects that the joke is at nobody's expense but his own.

However, nothing dispirits, and nothing seems worth while disputing. He

bolts down all events, all creeds, and beliefs, and persuasions, all

hard things visible and invisible, never mind how knobby; as an ostrich

of potent digestion gobbles down bullets and gun flints. And as for

small difficulties and worryings, prospects of sudden disaster, peril

of life and limb; all these, and death itself, seem to him only sly,

good-natured hits, and jolly punches in the side bestowed by the unseen

and unaccountable old joker. That odd sort of wayward mood I am

speaking of, comes over a man only in some time of extreme tribulation;

it comes in the very midst of his earnestness, so that what just before

might have seemed to him a thing most momentous, now seems but a part

of the general joke. There is nothing like the perils of whaling to

breed this free and easy sort of genial, desperado philosophy; and with

it I now regarded this whole voyage of the Pequod, and the great White

Whale its object.

“There are some enterprises in which a careful disorderliness is the true method.”

In the Shore Whaling, on soundings,

among the Bays of New Zealand, when a Right Whale gives token of

sinking, they fasten buoys to him, with plenty of rope; so that when

the body has gone down, they know where to look for it when it shall

have ascended again.

It was not long after the sinking of the body that a cry was heard from

the Pequod's mast-heads, announcing that the Jungfrau was again

lowering her boats; though the only spout in sight was that of a

Fin-Back, belonging to the species of uncapturable whales, because of

its incredible power of swimming. Nevertheless, the Fin-Back's spout is

so similar to the Sperm Whale's, that by unskilful fishermen it is

often mistaken for it. And consequently Derick and all his host were

now in valiant chase of this unnearable brute. The Virgin crowding all

sail, made after her four young keels, and thus they all disappeared

far to leeward, still in bold, hopeful chase.

Oh! many are the Fin-Backs, and many are the Dericks, my friend.

CHAPTER 82

The Honor and Glory of Whaling

There are some enterprises in which a careful disorderliness is the

true method.

The more I dive into this matter of whaling, and push my researches up

to the very spring-head of it so much the more am I impressed with its

great honorableness and antiquity; and especially when I find so many

great demi-gods and heroes, prophets of all sorts, who one way or other

have shed distinction upon it, I am transported with the reflection

that I myself belong, though but subordinately, to so emblazoned a

fraternity.

The gallant Perseus, a son of Jupiter, was the first whaleman; and to

the eternal honor of our calling be it said, that the first whale

attacked by our brotherhood was not killed with any sordid intent.

Those were the knightly days of our profession, when we only bore arms

to succor the distressed, and not to fill men's lamp-feeders. Every one

knows the fine story of Perseus and Andromeda; how the lovely

Andromeda, the daughter of a king, was tied to a rock on the sea-coast,

and as Leviathan was in the very act of carrying her off, Perseus, the

prince of whalemen, intrepidly advancing, harpooned the monster, and

delivered and married the maid.

“It is not down in any map; true places never are.”

I no more felt unduly concerned for the landlord's policy of

insurance. I was only alive to the condensed confidential

comfortableness of sharing a pipe and a blanket with a real friend.

With our shaggy jackets drawn about our shoulders, we now passed the

Tomahawk from one to the other, till slowly there grew over us a blue

hanging tester of smoke, illuminated by the flame of the new-lit lamp.

Whether it was that this undulating tester rolled the savage away to

far distant scenes, I know not, but he now spoke of his native island;

and, eager to hear his history, I begged him to go on and tell it. He

gladly complied. Though at the time I but ill comprehended not a few of

his words, yet subsequent disclosures, when I had become more familiar

with his broken phraseology, now enable me to present the whole story

such as it may prove in the mere skeleton I give.

CHAPTER 12

Biographical

Queequeg was a native of Kokovoko, an island far away to the West and

South. It is not down on any map; true places never are.

When a new-hatched savage running wild about his native woodlands in a

grass clout, followed by the nibbling goats, as if he were a green

sapling; even then, in Queequeg's ambitious soul, lurked a strong

desire to see something more of Christendom than a specimen whaler or

two. His father was a High Chief, a King; his uncle a High Priest; and

on the maternal side he boasted aunts who were the wives of

unconquerable warriors. There was excellent blood in his veins—royal

stuff; though sadly vitiated, I fear, by the cannibal propensity he

nourished in his untutored youth.

A Sag Harbor ship visited his father's bay, and Queequeg sought a

passage to Christian lands. But the ship, having her full complement of

seamen, spurned his suit; and not all the King his father's influence

could prevail. But Queequeg vowed a vow. Alone in his canoe, he paddled

off to a distant strait, which he knew the ship must pass through when

she quitted the island. On one side was a coral reef; on the other a

low tongue of land, covered with mangrove thickets that grew out into

the water.

“Heaven have mercy on us all - Presbyterians and Pagans alike - for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending”

CHAPTER 17

The Ramadan

As Queequeg's Ramadan, or Fasting and Humiliation, was to continue all

day, I did not choose to disturb him till towards night-fall; for I

cherish the greatest respect towards everybody's religious obligations,

never mind how comical, and could not find it in my heart to undervalue

even a congregation of ants worshipping a toad-stool; or those other

creatures in certain parts of our earth, who with a degree of

footmanism quite unprecedented in other planets, bow down before the

torso of a deceased landed proprietor merely on account of the

inordinate possessions yet owned and rented in his name.

I say, we good Presbyterian Christians should be charitable in these

things, and not fancy ourselves so vastly superior to other mortals,

pagans and what not, because of their half-crazy conceits on these

subjects. There was Queequeg, now, certainly entertaining the most

absurd notions about Yojo and his Ramadan;— but what of that? Queequeg

thought he knew what he was about, I suppose; he seemed to be content;

and there let him rest. All our arguing with him would not avail; let

him be, I say: and Heaven have mercy on us all—Presbyterians and Pagans

alike— for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and

sadly need mending.

Towards evening, when I felt assured that all his performances and

rituals must be over, I went up to his room and knocked at the door;

but no answer. I tried to open it, but it was fastened inside.

"Queequeg," said I softly through the key-hole:—all silent. "I say,

Queequeg! why don't you speak? It's I—Ishmael." But all remained still

as before. I began to grow alarmed. I had allowed him such abundant

time; I thought he might have had an apoplectic fit. I looked through

the key-hole; but the door opening into an odd corner of the room, the

key-hole prospect was but a crooked and sinister one. I could only see

part of the foot-board of the bed and a line of the wall, but nothing

more. I was surprised to behold resting against the wall the wooden

shaft of Queequeg's harpoon, which the landlady the evening previous

had taken from him, before our mounting to the chamber. That's strange,

thought I; but at any rate, since the harpoon stands yonder, and he

seldom or never goes abroad without it, therefore he must be inside

here, and no possible mistake.

“. . . these are the times of dreamy quietude, when beholding the tranquil beauty and brilliancy of the oceans skin, one forgets the tiger heart that pants beneath it; and would not willingly remember, that this velvet paw but conceals a remorseless fang.”

But ere he entered his

cabin, a light, unnatural, half-bantering, yet most piteous sound was

heard. Oh! Pip, thy wretched laugh, thy idle but unresting eye; all thy

strange mummeries not unmeaningly blended with the black tragedy of the

melancholy ship, and mocked it!

CHAPTER 114

The Gilder

Penetrating further and further into the heart of the Japanese cruising

ground the Pequod was soon all astir in the fishery. Often, in mild,

pleasant weather, for twelve, fifteen, eighteen, and twenty hours on

the stretch, they were engaged in the boats, steadily pulling, or

sailing, or paddling after the whales, or for an interlude of sixty or

seventy minutes calmly awaiting their uprising; though with but small

success for their pains.

At such times, under an abated sun; afloat all day upon smooth, slow

heaving swells; seated in his boat, light as a birch canoe; and so

sociably mixing with the soft waves themselves, that like hearth-stone

cats they purr against the gunwale; these are the times of dreamy

quietude, when beholding the tranquil beauty and brilliancy of the

ocean's skin, one forgets the tiger heart that pants beneath it; and

would not willingly remember, that this velvet paw but conceals a

remorseless fang.

These are the times, when in his whale-boat the rover softly feels a

certain filial, confident, land-like feeling towards the sea; that he

regards it as so much flowery earth; and the distant ship revealing

only the tops of her masts, seems struggling forward, not through high

rolling waves, but through the tall grass of a rolling prairie: as when

the western emigrants' horses only show their erected ears, while their

hidden bodies widely wade through the amazing verdure.

The long-drawn virgin vales; the mild blue hill-sides; as over these

there steals the hush, the hum; you almost swear that play-wearied

children lie sleeping in these solitudes, in some glad May-time, when

the flowers of the woods are plucked. And all this mixes with your most

mystic mood; so that fact and fancy, half-way meeting, interpenetrate,

and form one seamless whole.

Nor did such soothing scenes, however temporary, fail of at least as

temporary an effect on Ahab. But if these secret golden keys did seem

to open in him his own secret golden treasuries, yet did his breath

upon them prove but tarnishing.

“It is better to fail in originality than to succeed in imitation.”

But this is almost the case now. American authors have received

more just and discriminating praise (however loftily and ridiculously

given, in certain cases) even from some Englishmen, than from their own

countrymen. There are hardly five critics in America; and several of

them are asleep. As for patronage, it is the American author who now

patronizes his country, and not his country him. And if at times some

among them appeal to the people for more recognition, it is not always

with selfish motives, but patriotic ones.

It is true, that but few of them as yet have evinced that decided

originality which merits great praise. But that graceful writer, who

perhaps of all Americans has received the most plaudits from his own

country for his productions,--that very popular and amiable writer,

however good and self-reliant in many things, perhaps owes his chief

reputation to the self-acknowledged imitation of a foreign model, and

to the studied avoidance of all topics but smooth ones. But it is

better to fail in originality, than to succeed in imitation. He who has

never failed somewhere, that man cannot be great. Failure is the true

test of greatness. And if it be said, that continual success is a proof

that a man wisely knows his powers,--it is only to be added, that, in

that case, he knows them to be small. Let us believe it, then, once for

all, that there is no hope for us in these smooth, pleasing writers

that know their powers. Without malice, but to speak the plain fact,

they but furnish an appendix to Goldsmith, and other English authors.

And we want no American Goldsmiths, nay, we want no American Miltons.

It were the vilest thing you could say of a true American author, that

he were an American Tompkins. Call him an American and have done, for

you cannot say a nobler thing of him. But it is not meant that all

American writers should studiously cleave to nationality in their

writings; only this, no American writer should write like an Englishman

or a Frenchman; let him write like a man, for then he will be sure

to write like an American.

“To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme. No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea, though many there be that have tried it.”

And here be it said, that whenever

it has been convenient to consult one in the course of these

dissertations, I have invariably used a huge quarto edition of Johnson,

expressly purchased for that purpose; because that famous

lexicographer's uncommon personal bulk more fitted him to compile a

lexicon to be used by a whale author like me.

One often hears of writers that rise and swell with their subject,

though it may seem but an ordinary one. How, then, with me, writing of

this Leviathan? Unconsciously my chirography expands into placard

capitals. Give me a condor's quill! Give me Vesuvius' crater for an

inkstand! Friends, hold my arms! For in the mere act of penning my

thoughts of this Leviathan, they weary me, and make me faint with their

outreaching comprehensiveness of sweep, as if to include the whole

circle of the sciences, and all the generations of whales, and men, and

mastodons, past, present, and to come, with all the revolving panoramas

of empire on earth, and throughout the whole universe, not excluding

its suburbs. Such, and so magnifying, is the virtue of a large and

liberal theme! We expand to its bulk. To produce a mighty book, you

must choose a mighty theme. No great and enduring volume can ever be

written on the flea, though many there be who have tried it.

Ere entering upon the subject of Fossil Whales, I present my

credentials as a geologist, by stating that in my miscellaneous time I

have been a stone-mason, and also a great digger of ditches, canals and

wells, wine-vaults, cellars, and cisterns of all sorts. Likewise, by

way of preliminary, I desire to remind the reader, that while in the

earlier geological strata there are found the fossils of monsters now

almost completely extinct; the subsequent relics discovered in what are

called the Tertiary formations seem the connecting, or at any rate

intercepted links, between the antichronical creatures, and those whose

remote posterity are said to have entered the Ark; all the Fossil

Whales hitherto discovered belong to the Tertiary period, which is the

last preceding the superficial formations. And though none of them

precisely answer to any known species of the present time, they are yet

sufficiently akin to them in general respects, to justify their taking

ranks as Cetacean fossils.

“To the last, I grapple with thee; From Hells heart, I stab at thee; For hates sake, I spit my last breath at thee”

"The ship! The hearse!—the second hearse!" cried Ahab from the boat;

"its wood could only be American!"

Diving beneath the settling ship, the whale ran quivering along its

keel; but turning under water, swiftly shot to the surface again, far

off the other bow, but within a few yards of Ahab's boat, where, for a

time, he lay quiescent.

"I turn my body from the sun. What ho, Tashtego! Let me hear thy

hammer. Oh! ye three unsurrendered spires of mine; thou uncracked keel;

and only god-bullied hull; thou firm deck, and haughty helm, and

Pole-pointed prow,—death—glorious ship! must ye then perish, and

without me? Am I cut off from the last fond pride of meanest

shipwrecked captains? Oh, lonely death on lonely life! Oh, now I feel

my topmost greatness lies in my topmost grief. Ho, ho! from all your

furthest bounds, pour ye now in, ye bold billows of my whole foregone

life, and top this one piled comber of my death! Towards thee I roll,

thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with

thee; from hell's heart I stab at thee; for hate's sake I spit my last

breath at thee. Sink all coffins and all hearses to one common pool!

and since neither can be mine, let me then tow to pieces, while still

chasing thee, though tied to thee, thou damned whale! Thus, I give up

the spear!"

The harpoon was darted; the stricken whale flew forward; with igniting

velocity the line ran through the grooves;—ran foul. Ahab stooped to

clear it; he did clear it; but the flying turn caught him round the

neck, and voicelessly as Turkish mutes bowstring their victim, he was

shot out of the boat, ere the crew knew he was gone. Next instant, the

heavy eye-splice in the rope's final end flew out of the stark-empty

tub, knocked down an oarsman, and smiting the sea, disappeared in its

depths.

For an instant, the tranced boat's crew stood still; then turned. "The

ship? Great God, where is the ship?" Soon they through dim, bewildering

mediums saw her sidelong fading phantom, as in the gaseous Fata

Morgana; only the uppermost masts out of water; while fixed by

infatuation, or fidelity, or fate, to their once lofty perches, the

pagan harpooneers still maintained their sinking look-outs on the sea.

“..fiery yearnings their own phantom-futures make, and deem it present. So, after all these fearful, fainting trances, the verdict be, the golden haven was not gained - - yet, in bold quest thereof, better to sink in boundless deeps, than float on vulgar shoals; and give me, ye gods, an utter wreck, if wreck I do.”

Those who boldly launch, cast off

all cables; and turning from the common breeze, that’s fair for all,

with their own breath, fill their own sails. Hug the shore, naught new

is seen; and “Land ho!” at last was sung, when a new world was sought.

That voyager steered his bark through seas, untracked before; ploughed

his own path mid jeers; though with a heart that oft was heavy with the

thought, that he might only be too bold, and grope where land was none.

So I.

And though essaying but a sportive sail, I was driven from my course,

by a blast resistless; and ill-provided, young, and bowed to the brunt

of things before my prime, still fly before the gale;—hard have I

striven to keep stout heart.

And if it harder be, than e’er before, to find new climes, when now our

seas have oft been circled by ten thousand prows,—much more the glory!

But this new world here sought, is stranger far than his, who stretched

his vans from Palos. It is the world of mind; wherein the wanderer may

gaze round, with more of wonder than Balboa’s band roving through the

golden Aztec glades.

But fiery yearnings their own phantom-future make, and deem it present.

So, if after all these fearful, fainting trances, the verdict be, the

golden haven was not gained;—yet, in bold quest thereof, better to sink

in boundless deeps, than float on vulgar shoals; and give me, ye gods,

an utter wreck, if wreck I do.

CHAPTER LXVI.

A Flight Of Nightingales From Yoomy’s Mouth

By noon, down came a calm.

“Oh Neeva! good Neeva! kind Neeva! thy sweet breath, dear Neeva!”

So from his shark’s-mouth prayed little Vee-Vee to the god of Fair

Breezes. And along they swept; till the three prows neighed to the

blast; and pranced on their path, like steeds of Crusaders.

Now, that this fine wind had sprung up; the sun riding joyously in the

heavens; and the Lagoon all tossed with white, flying manes; Media

called upon Yoomy to ransack his whole assortment of songs:—warlike,

amorous, and sentimental,—and regale us with something inspiring for

too long the company had been gloomy.

“Thy best,” he cried.

Then will I e’en sing you a song, my lord, which is a song-full of

songs. I composed it long, long since, when Yillah yet bowered in Odo.

Ere now, some fragments have been heard. Ah, Taji! in this my lay, live

over again your happy hours. Some joys have thousand lives; can never

die; for when they droop, sweet memories bind them up.

Cannibals? Who is not a cannibal? I tell you it will be more tolerable for the Fejee that salted down a lean missionary in his cellar against a coming famine; it will be more tolerable for that provident Fejee, I say, in the day of judgement, than for thee, civilized and enlightened gourmand, who nailest geese to the ground and feastest on their bloated livers in thy pate de fois gras.

The casket of the skull is broken into with an axe, and the two

plump, whitish lobes being withdrawn (precisely resembling two large

puddings), they are then mixed with flour, and cooked into a most

delectable mess, in flavor somewhat resembling calves' head, which is

quite a dish among some epicures; and every one knows that some young

bucks among the epicures, by continually dining upon calves' brains, by

and by get to have a little brains of their own, so as to be able to

tell a calf's head from their own heads; which, indeed, requires

uncommon discrimination. And that is the reason why a young buck with

an intelligent looking calf's head before him, is somehow one of the

saddest sights you can see. The head looks a sort of reproachfully at

him, with an "Et tu Brute!" expression.

It is not, perhaps, entirely because the whale is so excessively

unctuous that landsmen seem to regard the eating of him with

abhorrence; that appears to result, in some way, from the consideration

before mentioned: i.e. that a man should eat a newly murdered thing of

the sea, and eat it too by its own light. But no doubt the first man

that ever murdered an ox was regarded as a murderer; perhaps he was

hung; and if he had been put on his trial by oxen, he certainly would

have been; and he certainly deserved it if any murderer does. Go to the

meat-market of a Saturday night and see the crowds of live bipeds

staring up at the long rows of dead quadrupeds. Does not that sight

take a tooth out of the cannibal's jaw? Cannibals? who is not a

cannibal? I tell you it will be more tolerable for the Fejee that

salted down a lean missionary in his cellar against a coming famine; it

will be more tolerable for that provident Fejee, I say, in the day of

judgment, than for thee, civilized and enlightened gourmand, who

nailest geese to the ground and feastest on their bloated livers in thy

pate-de-foie-gras.

But Stubb, he eats the whale by its own light, does he? and that is

adding insult to injury, is it? Look at your knife-handle, there, my

civilized and enlightened gourmand, dining off that roast beef, what is

that handle made of?—what but the bones of the brother of the very ox

you are eating? And what do you pick your teeth with, after devouring

that fat goose? With a feather of the same fowl. And with what quill

did the Secretary of the Society for the Suppression of Cruelty to

Ganders formally indite his circulars? It is only within the last month

or two that that society passed a resolution to patronize nothing but

steel pens.

CHAPTER 66

The Shark Massacre

When in the Southern Fishery a captured Sperm Whale, after long and

weary toil, is brought alongside late at night, it is not, as a general

thing at least, customary to proceed at once to the business of cutting

him in. For that business is an exceedingly laborious one; is not very

soon completed; and requires all hands to set about it.

So, when on one side you hoist in Lockes head, you go over that way; but now, on the other side, hoist in Kants and you come back again; but in very poor plight. Thus, some minds for ever keep trimming boat. Oh, ye foolish! throw all these thunder-heads overboard, and then you will float light and right.

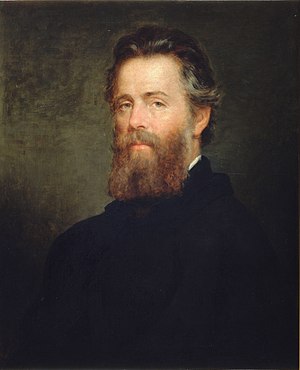

‘Clarel, a Poem and Pilgrimage

in the Holy Land’ (1876), is a long mystical poem requiring, as some one

has said, a dictionary, a cyclopaedia, and a copy of the Bible for its

elucidation. In the two privately printed volumes, the arrangement of

which occupied Mr. Melville during his last illness, there are several

fine lyrics. The titles of these books are, ‘John Marr and Other

Sailors’ (1888), and ‘Timoleon’ (1891).

There is no question that Mr. Melville’s absorption in philosophical

studies was quite as responsible as the failure of his later books for

his cessation from literary productiveness. That he sometimes realised

the situation will be seen by a passage in ‘Moby Dick’:--

‘Didn’t I tell you so?’ said Flask. ‘Yes, you’ll soon see this right

whale’s head hoisted up opposite that parmacetti’s.’

‘In good time Flask’s saying proved true. As before, the Pequod steeply

leaned over towards the sperm whale’s head, now, by the counterpoise of

both heads, she regained her own keel, though sorely strained, you may

well believe. So, when on one side you hoist in Locke’s head, you go

over that way; but now, on the other side, hoist in Kant’s and you

come back again; but in very poor plight. Thus, some minds forever keep

trimming boat. Oh, ye foolish! throw all these thunderheads overboard,

and then you will float right and light.’

Mr. Melville would have been more than mortal if he had been indifferent

to his loss of popularity. Yet he seemed contented to preserve an

entirely independent attitude, and to trust to the verdict of the

future. The smallest amount of activity would have kept him before the

public; but his reserve would not permit this. That reinstatement of his

reputation cannot be doubted.

In the editing of this reissue of ‘Melville’s Works,’ I have been

much indebted to the scholarly aid of Dr. Titus Munson Coan, whose

familiarity with the languages of the Pacific has enabled me to

harmonise the spelling of foreign words in ‘Typee’ and ‘Omoo,’ though

without changing the phonetic method of printing adopted by Mr.

Melville. Dr. Coan has also been most helpful with suggestions in other

directions. Finally, the delicate fancy of La Fargehas supplemented the

immortal pen-portrait of the Typee maiden with a speaking impersonation

of her beauty.

New York, June, 1892.

TYPEE

CHAPTER ONE

THE SEA--LONGINGS FOR SHORE--A LAND-SICK SHIP--DESTINATION OF THE

VOYAGERS--THE MARQUESAS--ADVENTURE OF A MISSIONARY’S WIFE AMONG THE

SAVAGES--CHARACTERISTIC ANECDOTE OF THE QUEEN OF NUKUHEVA

Six months at sea!

Is it not curious, that so vast a being as the whale should see the world through so small an eye, and hear the thunder through an ear which is smaller than a hares? But if his eyes were broad as the lens of Herschels great telescope; and his ears capacious as the porches of cathedrals; would that make him any longer of sight, or sharper of hearing? Not at all.—Why then do you try to enlarge your mind? Subtilize it

It may be but an idle whim, but it has always seemed to me, that the

extraordinary vacillations of movement displayed by some whales when

beset by three or four boats; the timidity and liability to queer

frights, so common to such whales; I think that all this indirectly

proceeds from the helpless perplexity of volition, in which their

divided and diametrically opposite powers of vision must involve them.

But the ear of the whale is full as curious as the eye. If you are an

entire stranger to their race, you might hunt over these two heads for

hours, and never discover that organ. The ear has no external leaf

whatever; and into the hole itself you can hardly insert a quill, so

wondrously minute is it. It is lodged a little behind the eye. With

respect to their ears, this important difference is to be observed

between the sperm whale and the right. While the ears of the former has

an external opening, that of the latter is entirely and evenly covered

over with a membrane, so as to be quite imperceptible from without.

Is it not curious, that so vast a being as the whale should see the

world through so small an eye, and hear the thunder through an ear

which is smaller than a hare's? But if his eyes were broad as the lens

of Herschel's great telescope; and his ears capacious as the porches of

cathedrals; would that make him any longer of sight, or sharper of

hearing? Not at all.—Why then do you try to "enlarge" your mind?

Subtilize it.

Let us now with whatever levers and steam-engines we have at hand, cant

over the sperm whale's head, so, that it may lie bottom up; then,

ascending by a ladder to the summit, have a peep down the mouth; and

were it not that the body is now completely separated from it, with a

lantern we might descend into the great Kentucky Mammoth Cave of his

stomach. But let us hold on here by this tooth, and look about us where

we are. What a really beautiful and chaste-looking mouth! from floor to

ceiling, lined, or rather papered with a glistening white membrane,

glossy as bridal satins.

But come out now, and look at this portentous lower jaw, which seems

like the long narrow lid of an immense snuff-box, with the hinge at one

end, instead of one side. If you pry it up, so as to get it overhead,

and expose its rows of teeth, it seems a terrific portcullis; and such,

alas! it proves to many a poor wight in the fishery, upon whom these

spikes fall with impaling force. But far more terrible is it to behold,

when fathoms down in the sea, you see some sulky whale, floating there

suspended, with his prodigious jaw, some fifteen feet long, hanging

straight down at right-angles with his body; for all the world like a

ship's jibboom.

Queequeg was a native of Kokovoko, an island far away to the West and South. It is not down in any map; true places never are.

For now I liked nothing better than to have Queequeg smoking by me,

even in bed, because he seemed to be full of such serene household joy

then. I no more felt unduly concerned for the landlord's policy of

insurance. I was only alive to the condensed confidential

comfortableness of sharing a pipe and a blanket with a real friend.

With our shaggy jackets drawn about our shoulders, we now passed the

Tomahawk from one to the other, till slowly there grew over us a blue

hanging tester of smoke, illuminated by the flame of the new-lit lamp.

Whether it was that this undulating tester rolled the savage away to

far distant scenes, I know not, but he now spoke of his native island;

and, eager to hear his history, I begged him to go on and tell it. He

gladly complied. Though at the time I but ill comprehended not a few of

his words, yet subsequent disclosures, when I had become more familiar

with his broken phraseology, now enable me to present the whole story

such as it may prove in the mere skeleton I give.

CHAPTER 12

Biographical

Queequeg was a native of Kokovoko, an island far away to the West and

South. It is not down on any map; true places never are.

When a new-hatched savage running wild about his native woodlands in a

grass clout, followed by the nibbling goats, as if he were a green

sapling; even then, in Queequeg's ambitious soul, lurked a strong

desire to see something more of Christendom than a specimen whaler or

two. His father was a High Chief, a King; his uncle a High Priest; and

on the maternal side he boasted aunts who were the wives of

unconquerable warriors. There was excellent blood in his veins—royal

stuff; though sadly vitiated, I fear, by the cannibal propensity he

nourished in his untutored youth.

A Sag Harbor ship visited his father's bay, and Queequeg sought a

passage to Christian lands. But the ship, having her full complement of

seamen, spurned his suit; and not all the King his father's influence

could prevail. But Queequeg vowed a vow. Alone in his canoe, he paddled

off to a distant strait, which he knew the ship must pass through when

she quitted the island. On one side was a coral reef; on the other a

low tongue of land, covered with mangrove thickets that grew out into

the water.

But vain to popularize profundities, and all truth is profound.

And, when

running into more sufferable latitudes, the ship, with mild stun'sails

spread, floated across the tranquil tropics, and, to all appearances,

the old man's delirium seemed left behind him with the Cape Horn

swells, and he came forth from his dark den into the blessed light and

air; even then, when he bore that firm, collected front, however pale,

and issued his calm orders once again; and his mates thanked God the

direful madness was now gone; even then, Ahab, in his hidden self,

raved on. Human madness is oftentimes a cunning and most feline thing.

When you think it fled, it may have but become transfigured into some

still subtler form. Ahab's full lunacy subsided not, but deepeningly

contracted; like the unabated Hudson, when that noble Northman flows

narrowly, but unfathomably through the Highland gorge. But, as in his

narrow-flowing monomania, not one jot of Ahab's broad madness had been

left behind; so in that broad madness, not one jot of his great natural

intellect had perished. That before living agent, now became the living

instrument. If such a furious trope may stand, his special lunacy

stormed his general sanity, and carried it, and turned all its

concentred cannon upon its own mad mark; so that far from having lost

his strength, Ahab, to that one end, did now possess a thousand fold

more potency than ever he had sanely brought to bear upon any one

reasonable object.

This is much; yet Ahab's larger, darker, deeper part remains unhinted.

But vain to popularize profundities, and all truth is profound. Winding

far down from within the very heart of this spiked Hotel de Cluny where

we here stand—however grand and wonderful, now quit it;— and take your

way, ye nobler, sadder souls, to those vast Roman halls of Thermes;

where far beneath the fantastic towers of man's upper earth, his root

of grandeur, his whole awful essence sits in bearded state; an antique

buried beneath antiquities, and throned on torsoes! So with a broken

throne, the great gods mock that captive king; so like a Caryatid, he

patient sits, upholding on his frozen brow the piled entablatures of

ages. Wind ye down there, ye prouder, sadder souls! question that

proud, sad king! A family likeness! aye, he did beget ye, ye young

exiled royalties; and from your grim sire only will the old

State-secret come.

Now, in his heart, Ahab had some glimpse of this, namely; all my means

are sane, my motive and my object mad. Yet without power to kill, or

change, or shun the fact; he likewise knew that to mankind he did now

long dissemble; in some sort, did still.

The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul. Not drowned entirely, though. Rather carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad. So man’s insanity is heaven’s sense; and wandering from all mortal reason, man comes at last to that celestial thought, which, to reason, is absurd and frantic; and weal or woe, feels then uncompromised, indifferent as his God.

But had Stubb really abandoned the poor little negro to his fate? No;

he did not mean to, at least. Because there were two boats in his wake,

and he supposed, no doubt, that they would of course come up to Pip

very quickly, and pick him up; though, indeed, such considerations

towards oarsmen jeopardized through their own timidity, is not always

manifested by the hunters in all similar instances; and such instances

not unfrequently occur; almost invariably in the fishery, a coward, so

called, is marked with the same ruthless detestation peculiar to

military navies and armies.

But it so happened, that those boats, without seeing Pip, suddenly

spying whales close to them on one side, turned, and gave chase; and

Stubb's boat was now so far away, and he and all his crew so intent

upon his fish, that Pip's ringed horizon began to expand around him

miserably. By the merest chance the ship itself at last rescued him;

but from that hour the little negro went about the deck an idiot; such,

at least, they said he was. The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body

up, but drowned the infinite of his soul. Not drowned entirely, though.

Rather carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of

the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes;

and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the

joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous,

God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters

heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God's foot upon the treadle of the

loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad. So

man's insanity is heaven's sense; and wandering from all mortal reason,

man comes at last to that celestial thought, which, to reason, is

absurd and frantic; and weal or woe, feels then uncompromised,

indifferent as his God.

For the rest blame not Stubb too hardly. The thing is common in that

fishery; and in the sequel of the narrative, it will then be seen what

like abandonment befell myself.

CHAPTER 94

A Squeeze of the Hand

That whale of Stubb's, so dearly purchased, was duly brought to the

Pequod's side, where all those cutting and hoisting operations

previously detailed, were regularly gone through, even to the baling of

the Heidelburgh Tun, or Case.

While some were occupied with this latter duty, others were employed in

dragging away the larger tubs, so soon as filled with the sperm; and

when the proper time arrived, this same sperm was carefully manipulated

ere going to the try-works, of which anon.

It had cooled and crystallized to such a degree, that when, with

several others, I sat down before a large Constantine's bath of it, I

found it strangely concreted into lumps, here and there rolling about

in the liquid part. It was our business to squeeze these lumps back

into fluid.

Give not thyself up, then, to fire, lest it invert thee, deaden thee, as for the time it did me. There is a wisdom that is woe; but there is a woe that is madness.

The sun hides not the ocean,

which is the dark side of this earth, and which is two thirds of this

earth. So, therefore, that mortal man who hath more of joy than sorrow

in him, that mortal man cannot be true—not true, or undeveloped. With

books the same. The truest of all men was the Man of Sorrows, and the

truest of all books is Solomon's, and Ecclesiastes is the fine hammered

steel of woe. "All is vanity." ALL. This wilful world hath not got hold

of unchristian Solomon's wisdom yet. But he who dodges hospitals and

jails, and walks fast crossing graveyards, and would rather talk of

operas than hell; calls Cowper, Young, Pascal, Rousseau, poor devils

all of sick men; and throughout a care-free lifetime swears by Rabelais

as passing wise, and therefore jolly;—not that man is fitted to sit

down on tomb-stones, and break the green damp mould with unfathomably

wondrous Solomon.

But even Solomon, he says, "the man that wandereth out of the way of

understanding shall remain" (i.e. even while living) "in the

congregation of the dead." Give not thyself up, then, to fire, lest it

invert thee, deaden thee; as for the time it did me. There is a wisdom

that is woe; but there is a woe that is madness. And there is a

Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down into the blackest

gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny

spaces. And even if he for ever flies within the gorge, that gorge is

in the mountains; so that even in his lowest swoop the mountain eagle

is still higher than other birds upon the plain, even though they soar.

CHAPTER 97

The Lamp

Had you descended from the Pequod's try-works to the Pequod's

forecastle, where the off duty watch were sleeping, for one single

moment you would have almost thought you were standing in some

illuminated shrine of canonized kings and counsellors. There they lay

in their triangular oaken vaults, each mariner a chiselled muteness; a

score of lamps flashing upon his hooded eyes.

In merchantmen, oil for the sailor is more scarce than the milk of

queens. To dress in the dark, and eat in the dark, and stumble in

darkness to his pallet, this is his usual lot. But the whaleman, as he

seeks the food of light, so he lives in light.

“Roll on, thou deep and dark blue Ocean - roll! / Ten thousand fleets sweep over thee in vain; / Man marks the earth with ruin - his control / Stops with the shore.”

“Friendship at first sight, like love at first sight is said to be the only truth”

“Art is the objectification of feeling.”

“Hope is the struggle of the soul, breaking loose from what is perishable, and attesting her eternity”