“A blessed thing it is for any man or woman to have a friend, one human soul whom we can trust utterly, who knows the best and worst of us, and who loves us in spite of all our faults.”

On the contrary, you will find in practice

that it is only the meanest hearts, the shallowest and the basest,

who feel no admiration, but only envy for those who are better than

themselves; who delight in finding fault with them, and blackening

their character, and showing that they are not, after all, so much

superior to other people; while it is the noblest-hearted, the very

men who are most worthy to be admired themselves, who, like

Jonathan, feel most the pleasure, the joy, and the strength of

reverence; of having some one whom they can look up to and admire;

some one in whose company they can forget themselves, their own

interest, their own pleasure, their own honour and glory, and cry,

Him I must hear; him I must follow; to him I must cling, whatever

may betide. Blessed and ennobling is the feeling which gathers

round a wise teacher or a great statesman all the most earnest,

high-minded, and pious youths of his generation; the feeling which

makes soldiers follow the general whom they trust, they know not why

or whither, through danger, and hunger, and fatigue, and death

itself; the feeling which, in its highest perfection, made the

Apostles forsake all and follow Christ, saying, 'Lord, to whom shall

we go? Thou hast the words of eternal life'--which made them ready

to work and to die for him whom the world called the son of the

carpenter, but whom they, through the Spirit of God bearing witness

with their own pure and noble spirits, knew to be the Son of the

Living God.

Ay, a blessed thing it is for any man or woman to have a friend; one

human soul whom we can trust utterly; who knows the best and the

worst of us, and who loves us, in spite of all our faults; who will

speak the honest truth to us, while the world flatters us to our

face, and laughs at us behind our back; who will give us counsel and

reproof in the day of prosperity and self-conceit; but who, again,

will comfort and encourage us in the day of difficulty and sorrow,

when the world leaves us alone to fight our own battle as we can.

If we have had the good fortune to win such a friend, let us do

anything rather than lose him. We must give and forgive; live and

let live. If our friend have faults, we must bear with them. We

must hope all things, believe all things, endure all things, rather

than lose that most precious of all earthly possessions--a trusty

friend.

And a friend, once won, need never be lost, if we will only be

trusty and true ourselves. Friends may part--not merely in body,

but in spirit, for a while. In the bustle of business and the

accidents of life they may lose sight of each other for years; and

more--they may begin to differ in their success in life, in their

opinions, in their habits, and there may be, for a time, coldness

and estrangement between them; but not for ever, if each will be but

trusty and true.

“Pain is no evil, unless it conquers us”

But they laughed;

All but one soldier, gray, with many scars;

And he stood silent. Then I crawled to you,

And kissed your bleeding feet, and called aloud--

You heard me! You know all! I am at peace.

Peace, peace, as still and bright as is the moon

Upon your limbs, came on me at your smile,

And kept me happy, when they dragged me back

From that last kiss, and spread me on the cross,

And bound my wrists and ankles--Do not sigh:

I prayed, and bore it: and since they raised me up

My eyes have never left your face, my own, my own,

Nor will, till death comes! . . .

Do I feel much pain?

Not much. Not maddening. None I cannot bear.

It has become like part of my own life,

Or part of God's life in me--honour--bliss!

I dreaded madness, and instead comes rest;

Rest deep and smiling, like a summer's night.

I should be easy, now, if I could move . . .

I cannot stir. Ah God! these shoots of fire

Through all my limbs! Hush, selfish girl! He hears you!

Who ever found the cross a pleasant bed?

Yes; I can bear it, love. Pain is no evil

Unless it conquers us. These little wrists, now--

You said, one blessed night, they were too slender,

Too soft and slender for a deacon's wife--

Perhaps a martyr's:--You forgot the strength

Which God can give. The cord has cut them through;

And yet my voice has never faltered yet.

Oh! do not groan, or I shall long and pray

That you may die: and you must not die yet.

Not yet--they told us we might live three days . . .

Two days for you to preach! Two days to speak

Words which may wake the dead!

. . . . .

Hush! is he sleeping?

They say that men have slept upon the cross;

So why not he? . . . Thanks, Lord! I hear him breathe:

And he will preach Thy word to-morrow!--save

Souls, crowds, for Thee! And they will know his worth

Years hence--poor things, they know not what they do!--

And crown him martyr; and his name will ring

Through all the shores of earth, and all the stars

Whose eyes are sparkling through their tears to see

His triumph--Preacher! Martyr!--Ah--and me?--

If they must couple my poor name with his,

Let them tell all the truth--say how I loved him,

And tried to damn him by that love!

“It is only the great hearted who can be true friends. The mean and cowardly, Can never know what true friendship means.”

And we

shall be made truly wise if we be made content; content, too, not only

with what we can understand, but content with what we do not

understand--the habit of mind which theologians call (and rightly) faith

in God, true and solid faith, which comes often out of sadness and out of

doubt.

_Lecture on Bio-geology_. 1869.

Duty of Man to Man. March 12.

Each man can learn something from his neighbour; at least he can learn

this--to have patience with his neighbour, to live and let live.

Peace! peace! Anything which is not _wrong_ for the sake of heaven-born

Peace!

_Town and Country Sermons_. 1861.

Blessing of a True Friend. March 13.

A blessed thing it is for any man or woman to have a friend, one human

soul whom we can trust utterly, who knows the best and worst of us, and

who loves us in spite of all our faults; who will speak the honest truth

to us, while the world flatters us to our face, and laughs at us behind

our back; who will give us counsel and reproof in the days of prosperity

and self-conceit; but who, again, will comfort and encourage us in the

day of difficulty and sorrow, when the world leaves us alone to fight our

battle as we can.

It is only the great-hearted who can be true friends: the mean and

cowardly can never know what true friendship means.

_Sermons on David_. 1866.

True Heroines. March 14.

What is the commonest, and yet the least remembered form of heroism? The

heroism of an average mother. Ah! when I think of that broad fact I

gather hope again for poor humanity, and this dark world looks bright,

this diseased world looks wholesome to me once more, because, whatever

else it is or is not full of, it is at least full of mothers.

_Lecture on Heroism_. 1873.

Secret Atheism. March 15.

There is little hope that we shall learn the lessons God is for ever

teaching us in the events of life till we get rid of our secret Atheism,

till we give up the notion that God only visits now and then to disorder

and destroy His own handiwork, and take back the old scriptural notion

that God is visiting all day long for ever, to give order and life to His

own work, to set it right where it goes wrong, and re-create it whenever

it decays.

_Water of Life Sermons_. 1866.

Tolerance. March 16.

“There are two freedoms; The false, where man is free to do what he likes; The true, where man is free to do what he ought.”

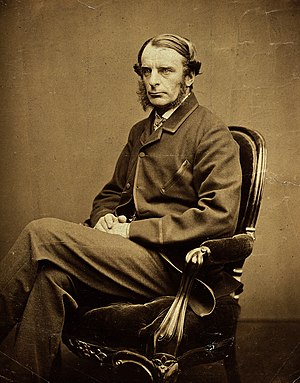

Kingsley took precisely

that view of the message of the Church to labouring men which every reader

of his books would have expected him to take."

Kingsley took his text from Luke iv. verses 16 to 21: "The spirit of the

Lord is upon me because He hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the

poor," &c. What then was that gospel? Kingsley asks, and goes on--"I assert

that the business for which God sends a Christian priest in a Christian

nation is, to preach freedom, equality, and brotherhood in the fullest,

deepest, widest meaning of those three great words; that in as far as he so

does, he is a true priest, doing his Lord's work with his Lord's blessing

on him; that in as far as he does not he is no priest at all, but a traitor

to God and man"; and again, "I say that these words express the very

pith and marrow of a priest's business; I say that they preach freedom,

equality, and brotherhood to rich and poor for ever and ever." Then he goes

on to warn his hearers how there is always a counterfeit in this world of

the noblest message and teaching.

Thus there are two freedoms--the false, where a man is free to do what he

likes; the true, where a man is free to do what he ought.

Two equalities--the false, which reduces all intellects and all characters,

to a dead level, and gives the same power to the bad as to the good, to the

wise as to the foolish, ending thus in practice in the grossest inequality;

the true, wherein each man has equal power to educate and use whatever

faculties or talents God has given him, be they less or more. This is the

divine equality which the Church proclaims, and nothing else proclaims as

she does.

Two brotherhoods--the false, where a man chooses who shall be his brothers,

and whom he will treat as such; the true, in which a man believes that

all are his brothers, not by the will of the flesh, or the will of man,

but by the will of God, whose children they all are alike. The Church has

three special possessions and treasures. The Bible, which proclaims man's

freedom, Baptism his equality, the Lord's Supper his brotherhood.

At the end of this sermon (which would scarcely cause surprise to-day

if preached by the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Chapel Royal), the

incumbent got up at the altar and declared his belief that great part of

the doctrine of the sermon was untrue, and that he had expected a sermon of

an entirely different kind.

“Except a living man, there is nothing more wonderful than a book.”

How it should make us

reverence the Bible, the written word of God’s saints and prophets, of

God’s apostles, of Christ, the Word Himself? Oh, that men would use that

treasure of the Bible as it deserves;—oh, that they would believe from

their hearts, that whatever is said there is truly said, that whatever is

said there is said to them, that whatever names things are called there

are called by their right names. Then men would no longer call the vile

person beautiful, or call pride and vanity honour, or covetousness

respectability, or call sin worldly wisdom; but they would call things as

Christ calls them—they would try to copy Christ’s thoughts and Christ’s

teaching; and instead of looking for instruction and comfort to lying

opinions and false worldly cunning, they would find their only advice in

the blessed teaching, and their only comfort in the gracious promises, of

the word of the Book of Life.

Again, how these thoughts ought to make us reverence all books.

Consider! except a living man, there is nothing more wonderful than a

book!—a message to us from the dead—from human souls whom we never saw,

who lived, perhaps, thousands of miles away; and yet these, in those

little sheets of paper, speak to us, amuse us, terrify us, teach us,

comfort us, open their hearts to us as brothers.

Why is it that neither angels, nor saints, nor evil spirits, appear to

men now to speak to them as they did of old? Why, but because we have

_books_, by which Christ’s messengers, and the devil’s messengers too,

can tell what they will to thousands of human beings at the same moment,

year after year, all the world over! I say, we ought to reverence books,

to look at them as awful and mighty things. If they are good and true,

whether they are about religion or politics, farming, trade, or medicine,

they are the message of Christ, the Maker of all things, the Teacher of

all truth, which He has put into the heart of some man to speak, that he

may tell us what is good for our spirits, for our bodies, and for our

country.

And at the last day, be sure of it, we shall have to render an account—a

strict account, of the books which we have read, and of the way in which

we have obeyed what we read, just as if we had had so many prophets or

angels sent to us.

“Do noble things, not dream them all day long”

Why did not he, like the rest who dangled about her,

spread out his peacock's train for her eyes; and try to show his worship

of her, by setting himself off in his brightest colours? And yet this

modesty awed her into respect of him; for she could not forget that,

whether he had sentiment much or little, sentiment was not the staple of

his manhood: she could not forget his cholera work; and she knew that,

under that delicate and bashful outside, lay virtue and heroism, enough

and to spare.

"But, if you put these thoughts into words, you would teach others to

read that poetry."

"My business is to teach people to do right; and if I cannot, to pray

God to find some one who can."

"Right, Headley!" said Major Campbell, laying his hand on the Curate's

shoulder. "God dwells no more in books written with pens than in temples

made with hands; and the sacrifice which pleases Him is not verse, but

righteousness. Do you recollect, Queen Whims, what I wrote once in your

album?

'Be good, sweet maid, and let who will be clever

Do noble things, not dream them, all day long,

So making life, death, and that vast for ever,

One grand, sweet song.'"

"But, you naughty, hypocritical Saint Père, you write poetry yourself,

and beautifully."

"Yes, as I smoke my cigar, to comfort my poor rheumatic old soul. But if

I lived only to write poetry, I should think myself as wise as if I

lived only to smoke tobacco."

Valencia's eyes could not help glancing at Elsley, who had wandered away

to the neighbouring brook, and was gazing with all his eyes upon a ferny

rock, having left Lucia to help Claude with his photographing.

Frank saw her look, and read its meaning; and answered her thoughts,

perhaps too hastily.

"And what a really well-read and agreeable man he is, all the while!

What a mine of quaint learning, and beautiful old legend!--If he would

but bring it into the common stock for every one's amusement, instead of

hoarding it up for himself!" "Why, what else does he do but bring it

into the common stock, when he publishes a book which every one can

read!

“Being forced to work, and forced to do your best, will breed in you temperance and self-control, diligence and strength of will, cheerfulness and content, and a hundred virtues which the idle will never know.”

So it is, and so it should be; for

God has knit us all together as brethren, members of one family of

God; and the well-being of each makes up the well-being of all, so

that sooner or later, if one member rejoice, all the others rejoice

with it.

But more. And here I speak to young people; for their elders, I

doubt not, have found it out long since for themselves. Work, hard

work, is a blessing to the soul and character of the man who works.

Young men may not think so. They may say, What more pleasant than

to have one's fortune made for one, and have nothing before one than

to enjoy life? What more pleasant than to be idle: or, at least,

to do only what one likes, and no more than one likes? But they

would find themselves mistaken. They would find that idleness makes

a man restless, discontented, greedy, the slave of his own lusts and

passions, and see too late, that no man is more to be pitied than

the man who has nothing to do. Yes; thank God every morning, when

you get up, that you have something to do that day which must be

done, whether you like or not. Being forced to work, and forced to

do your best, will breed in you temperance and self-control,

diligence and strength of will, cheerfulness and content and a

hundred virtues which the idle man will never know. The monks in

old time found it so. When they shut themselves up from the world

to worship God in prayers and hymns, they found that, without

working, without hard work either of head or hands, they could not

even be good men. The devil came and tempted them, they said, as

often as they were idle. An idle monk's soul was lost, they used to

say; and they spoke truly. Though they gave up a large portion of

every day, and of every night also, to prayer and worship, yet they

found they could not pray aright without work. And 'working is

praying,' said one of the holiest of them that ever lived; and he

spoke truth, if a man will but do his work for the sake of duty,

which is for the sake of God. And so they worked, and worked hard,

not only at teaching the children of the poor, but at tilling the

ground, clearing the forests, building noble churches, which stand

unto this day; none among them were idle at first; and as long as

they worked, they were good men, and blessings to all around them,

and to this land of England, which they brought out of heathendom to

the knowledge of Christ and of God; and it was not till they became

rich and idle, and made other people work for them and till their

great estates, that they sank into sin and shame, and became

despised and hated, and at last swept off the face of the land.

“There is a great deal of human nature in man.”

’ Remember that you are claiming for yourselves the very highest

honour—an honour too great to make you proud; an honour so great that, if

you understand it rightly, it must fill you with awe, and trembling, and

the spirit of godly fear, lest, when God has put you up so high, you

should fall shamefully again. For the higher the place, the deeper the

fall; and the greater the honour, the greater the shame of losing it.

But be sure that it was an honour before Adam fell. That ever since

Christ has taken the manhood into God, it is an honour now to be a man.

Do not let the devil or bad men ever tempt you to say, I am only a man,

and therefore you cannot expect me to do right. I am but a man, and

therefore I cannot help being mean, and sinful, and covetous, and

quarrelsome, and foul: for that is the devil’s doctrine, though it is

common enough. I have heard a story of a man in America—where very few,

I am sorry to say, have heard the true doctrine of the Catholic Church,

and therefore do not know really that God made man in his own image, and

redeemed him again into his own image by Jesus Christ—and this man was

rebuked for being a drunkard; and what do you fancy his excuse was?

‘Ah,’ he said, ‘you should remember that there is a great deal of human

nature in a man.’ That was his excuse. He had been so ill-taught by his

Calvinist preachers, that he had learnt to look on human nature as

actually a bad thing; as if the devil, and not God, had made human

nature, and as if Christ had not redeemed human nature. Because he was a

man, he thought he was excused in being a bad man; because he had a human

nature in him, he was to be a drunkard and a brute.

My friends, I trust that you have not so learned Christ. And if you

have, it is from no teaching of your Bible, of your Catechism, or your

Prayer-book; and, I say boldly, from no teaching of mine. The Church

bids you say, Yes; I have a human nature in me; and what nature is that

but the nature which the Son of God took on himself, and redeemed, and

justified it, and glorified it, sitting for ever now in his human nature

at the right hand of God, the Son of man who is in heaven? Yes, I am a

man; and what is it to be a man, but to be the image and glory of God?

What is it to be a man?

The most wonderful and the strongest things in the world, you know, are just the things which no one can see.

And he had not been in it two minutes before he fell fast asleep, into

the quietest, sunniest, cosiest sleep that ever he had in his life; and

he dreamt about the green meadows by which he had walked that morning,

and the tall elm-trees, and the sleeping cows; and after that he dreamt

of nothing at all.

The reason of his falling into such a delightful sleep is very simple;

and yet hardly any one has found it out. It was merely that the fairies

took him.

Some people think that there are no fairies. Cousin Cramchild tells

little folks so in his Conversations. Well, perhaps there are none—in

Boston, U.S., where he was raised. There are only a clumsy lot of

spirits there, who can’t make people hear without thumping on the table:

but they get their living thereby, and I suppose that is all they want.

And Aunt Agitate, in her Arguments on political economy, says there are

none. Well, perhaps there are none—in her political economy. But it is

a wide world, my little man—and thank Heaven for it, for else, between

crinolines and theories, some of us would get squashed—and plenty of room

in it for fairies, without people seeing them; unless, of course, they

look in the right place. The most wonderful and the strongest things in

the world, you know, are just the things which no one can see. There is

life in you; and it is the life in you which makes you grow, and move,

and think: and yet you can’t see it. And there is steam in a

steam-engine; and that is what makes it move: and yet you can’t see it;

and so there may be fairies in the world, and they may be just what makes

the world go round to the old tune of

“_C’est l’amour_, _l’amour_, _l’amour_

_Qui fait la monde à la ronde_:”

[Picture: Fairy cherub with arrow] and yet no one may be able to see them

except those whose hearts are going round to that same tune. At all

events, we will make believe that there are fairies in the world. It

will not be the last time by many a one that we shall have to make

believe. And yet, after all, there is no need for that. There must be

fairies; for this is a fairy tale: and how can one have a fairy tale if

there are no fairies?

You don’t see the logic of that? Perhaps not. Then please not to see

the logic of a great many arguments exactly like it, which you will hear

before your beard is gray.

Did not learned men, too, hold, till within the last twenty-five years, that a flying dragon was an impossible monster? And do we not now know that there are hundreds of them found fossil up and down the world? People call them Pterodactyles: but that is only because they are ashamed to call them flying dragons, after denying so long that flying dragons could exist.

And suppose that you described him to people, and said, “This

is the shape, and plan, and anatomy of the beast, and of his feet, and of

his trunk, and of his grinders, and of his tusks, though they are not

tusks at all, but two fore teeth run mad; and this is the section of his

skull, more like a mushroom than a reasonable skull of a reasonable or

unreasonable beast; and so forth, and so forth; and though the beast

(which I assure you I have seen and shot) is first cousin to the little

hairy coney of Scripture, second cousin to a pig, and (I suspect)

thirteenth or fourteenth cousin to a rabbit, yet he is the wisest of all

beasts, and can do everything save read, write, and cast accounts.”

People would surely have said, “Nonsense; your elephant is contrary to

nature;” and have thought you were telling stories—as the French thought

of Le Vaillant when he came back to Paris and said that he had shot a

giraffe; and as the king of the Cannibal Islands thought of the English

sailor, when he said that in his country water turned to marble, and rain

fell as feathers. They would tell you, the more they knew of science,

“Your elephant is an impossible monster, contrary to the laws of

comparative anatomy, as far as yet known.” To which you would answer the

less, the more you thought.

Did not learned men, too, hold, till within the last twenty-five years,

that a flying dragon was an impossible monster? And do we not now know

that there are hundreds of them found fossil up and down the world?

People call them Pterodactyles: but that is only because they are ashamed

to call them flying dragons, after denying so long that flying dragons

could exist.

The truth is, that folks’ fancy that such and such things cannot be,

simply because they have not seen them, is worth no more than a savage’s

fancy that there cannot be such a thing as a locomotive, because he never

saw one running wild in the forest. Wise men know that their business is

to examine what is, and not to settle what is not. They know that there

are elephants; they know that there have been flying dragons; and the

wiser they are, the less inclined they will be to say positively that

there are no water-babies.

No water-babies, indeed? Why, wise men of old said that everything on

earth had its double in the water; and you may see that that is, if not

quite true, still quite as true as most other theories which you are

likely to hear for many a day. There are land-babies—then why not

water-babies? _Are there not water-rats_, _water-flies_,

_water-crickets_, _water-crabs_, _water-tortoises_, _water-scorpions_,

_water-tigers and water-hogs_, _water-cats and water-dogs_, _sea-lions

and sea-bears_, _sea-horses and sea-elephants_, _sea-mice and

sea-urchins_, _sea-razors and sea-pens_, _sea-combs and sea-fans_; _and

of plants_, _are there not water-grass_, _and water-crowfoot_,

_water-milfoil_, _and so on_, _without end_?

“We act as though comfort and luxury were the chief requirements of life, when all that we need to make us really happy is something to be enthusiastic about”

“Some say that the age of chivalry is past, that the spirit of romance is dead. The age of chivalry is never past, so long as there is a wrong left unredressed on earth.”

“Theres no use doing a kindness if you do it a day too late.”

“Tis the good reader that makes the good book.”

There is nothing more wonderful than a book. It may be a message to us from the dead, from human souls we never saw who lived perhaps thousands of miles away, and yet these little sheets of paper speak to us, arouse us, teach us, open our hearts and in turn open their hearts to us like brothers. Without books, God is silent, justice dormant, philosophy lame.

Some say that the age of chivalry is past, that the spirit of romance is dead. The age of chivalry is never past, so long as there is a wrong left unredressed on earth.

Except a living man there is nothing more wonderful than a book! A message from the dead - from human souls we never saw, who lived, perhaps, thousands of miles away. And yet these, in those little sheets of paper, speak to us, arouse us, terrify us, comfort us, open their hearts to us as brothers.

Friendship is like a glass ornament, once it is broken it can rarely be put back together exactly the same way.

Feelings are like chemicals, the more you analyze them the worse they smell.

Except a living man there is nothing more wonderful than a book! a message to us from... human souls we never saw... And yet these arouse us terrify us teach us comfort us open their hearts to us as brothers.