“One of the best things in the world to be is a boy; it requires no experience, but needs some practice to be a good one”

I know, indeed, that it is not always so; and

that, as Boreas is a better nurse of rugged virtue than Zephyr, so

the soft influences of this clime only minister to the fatal desires

of some: and such are likely to sail speedily back to Naples.

The Sirens, indeed, are everywhere; and I do not know that we can go

anywhere that we shall escape the infinite longings, or satisfy them.

Here, in the purple twilight of history, they offered men the choice

of good and evil. I have a fancy, that, in stepping out of the whirl

of modern life upon a quiet headland, so blessed of two powers, the

air and the sea, we are able to come to a truer perception of the

drift of the eternal desires within us. But I cannot say whether it

is a subtle fascination, linked with these mythic and moral

influences, or only the physical loveliness of this promontory, that

lures travelers hither, and detains them on flowery meads.

BEING A BOY

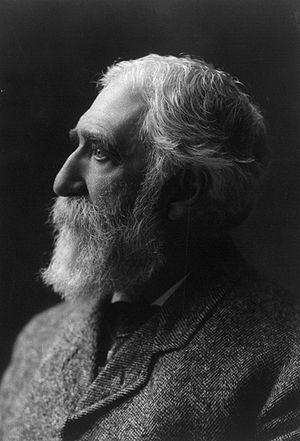

By Charles Dudley Warner

BEING A BOY

One of the best things in the world to be is a boy; it requires no

experience, though it needs some practice to be a good one. The

disadvantage of the position is that it does not last long enough; it

is soon over; just as you get used to being a boy, you have to be

something else, with a good deal more work to do and not half so much

fun. And yet every boy is anxious to be a man, and is very uneasy

with the restrictions that are put upon him as a boy. Good fun as it

is to yoke up the calves and play work, there is not a boy on a farm

but would rather drive a yoke of oxen at real work. What a glorious

feeling it is, indeed, when a boy is for the first time given the

long whip and permitted to drive the oxen, walking by their side,

swinging the long lash, and shouting "Gee, Buck!" "Haw, Golden!"

"Whoa, Bright!" and all the rest of that remarkable language, until

he is red in the face, and all the neighbors for half a mile are

aware that something unusual is going on. If I were a boy, I am not

sure but I would rather drive the oxen than have a birthday.

The proudest day of my life was one day when I rode on the neap of

the cart, and drove the oxen, all alone, with a load of apples to the

cider-mill.

“Happy is said to be the family which can eat onions together. They are, for the time being, separate, from the world, and have a harmony of aspiration.”

You take off coat after coat) and the onion is

still there; and, when the last one is removed, who dare say that the

onion itself is destroyed, though you can weep over its departed

spirit? If there is any one thing on this fallen earth that the

angels in heaven weep over--more than another, it is the onion.

I know that there is supposed to be a prejudice against the onion;

but I think there is rather a cowardice in regard to it. I doubt not

that all men and women love the onion; but few confess their love.

Affection for it is concealed. Good New-Englanders are as shy of

owning it as they are of talking about religion. Some people have

days on which they eat onions,--what you might call "retreats," or

their "Thursdays." The act is in the nature of a religious ceremony,

an Eleusinian mystery; not a breath of it must get abroad. On that

day they see no company; they deny the kiss of greeting to the

dearest friend; they retire within themselves, and hold communion

with one of the most pungent and penetrating manifestations of the

moral vegetable world. Happy is said to be the family which can eat

onions together. They are, for the time being, separate from the

world, and have a harmony of aspiration. There is a hint here for

the reformers. Let them become apostles of the onion; let them eat,

and preach it to their fellows, and circulate tracts of it in the

form of seeds. In the onion is the hope of universal brotherhood.

If all men will eat onions at all times, they will come into a

universal sympathy. Look at Italy. I hope I am not mistaken as to

the cause of her unity. It was the Reds who preached the gospel

which made it possible. All the Reds of Europe, all the sworn

devotees of the mystic Mary Ann, eat of the common vegetable. Their

oaths are strong with it. It is the food, also, of the common people

of Italy. All the social atmosphere of that delicious land is laden

with it. Its odor is a practical democracy. In the churches all are

alike: there is one faith, one smell. The entrance of Victor Emanuel

into Rome is only the pompous proclamation of a unity which garlic

had already accomplished; and yet we, who boast of our democracy, eat

onions in secret.

“The boy who expects every morning to open into a new world finds that today is like yesterday, but he believes tomorrow will be different”

How it

roars up the wide chimney, sending into the air the signal smoke and

sparks which announce to the farming neighbors another day cheerfully

begun! The sleepiest boy in the world would get up in his red

flannel nightgown to see such a fire lighted, even if he dropped to

sleep again in his chair before the ruddy blaze. Then it is that the

house, which has shrunk and creaked all night in the pinching cold of

winter, begins to glow again and come to life. The thick frost melts

little by little on the small window-panes, and it is seen that the

gray dawn is breaking over the leagues of pallid snow. It is time to

blow out the candle, which has lost all its cheerfulness in the light

of day. The morning romance is over; the family is astir; and member

after member appears with the morning yawn, to stand before the

crackling, fierce conflagration. The daily round begins. The most

hateful employment ever invented for mortal man presents itself: the

"chores" are to be done. The boy who expects every morning to open

into a new world finds that to-day is like yesterday, but he believes

to-morrow will be different. And yet enough for him, for the day, is

the wading in the snowdrifts, or the sliding on the diamond-sparkling

crust. Happy, too, is he, when the storm rages, and the snow is

piled high against the windows, if he can sit in the warm chimney-

corner and read about Burgoyne, and General Fraser, and Miss McCrea,

midwinter marches through the wilderness, surprises of wigwams, and

the stirring ballad, say, of the Battle of the Kegs:--

"Come, gallants, attend and list a friend

Thrill forth harmonious ditty;

While I shall tell what late befell

At Philadelphia city."

I should like to know what heroism a boy in an old New England

farmhouse--rough-nursed by nature, and fed on the traditions of the

old wars did not aspire to. "John," says the mother, "You'll burn

your head to a crisp in that heat." But John does not hear; he is

storming the Plains of Abraham just now. "Johnny, dear, bring in a

stick of wood." How can Johnny bring in wood when he is in that

defile with Braddock, and the Indians are popping at him from behind

every tree?

“Regrets are idle; yet history is one long regret. Everything might have turned out so differently.”

You recall your delight in

conversing with the nurseryman, and looking at his illustrated

catalogues, where all the pears are drawn perfect in form, and of

extra size, and at that exact moment between ripeness and decay which

it is so impossible to hit in practice. Fruit cannot be raised on

this earth to taste as you imagine those pears would taste. For

years you have this pleasure, unalloyed by any disenchanting reality.

How you watch the tender twigs in spring, and the freshly forming

bark, hovering about the healthy growing tree with your pruning-knife

many a sunny morning! That is happiness. Then, if you know it, you

are drinking the very wine of life; and when the sweet juices of the

earth mount the limbs, and flow down the tender stem, ripening and

reddening the pendent fruit, you feel that you somehow stand at the

source of things, and have no unimportant share in the processes of

Nature. Enter at this moment boy the destroyer, whose office is that

of preserver as well; for, though he removes the fruit from your

sight, it remains in your memory immortally ripe and desirable. The

gardener needs all these consolations of a high philosophy.

EIGHTEENTH WEEK

Regrets are idle; yet history is one long regret. Everything might

have turned out so differently! If Ravaillac had not been imprisoned

for debt, he would not have stabbed Henry of Navarre. If William of

Orange had escaped assassination by Philip's emissaries; if France

had followed the French Calvin, and embraced Protestant Calvinism, as

it came very near doing towards the end of the sixteenth century; if

the Continental ammunition had not given out at Bunker's Hill; if

Blucher had not "come up" at Waterloo,--the lesson is, that things do

not come up unless they are planted. When you go behind the

historical scenery, you find there is a rope and pulley to effect

every transformation which has astonished you. It was the rascality

of a minister and a contractor five years before that lost the

battle; and the cause of the defeat was worthless ammunition. I

should like to know how many wars have been caused by fits of

indigestion, and how many more dynasties have been upset by the love

of woman than by the hate of man. It is only because we are ill

informed that anything surprises us; and we are disappointed because

we expect that for which we have not provided.

“Perhaps nobody ever accomplishes all that he feels lies in him to do; but nearly every one who tries his power touches the walls of his being.”

That talk

must be very well in hand, and under great headway, that an anecdote

thrown in front of will not pitch off the track and wreck. And it

makes little difference what the anecdote is; a poor one depresses

the spirits, and casts a gloom over the company; a good one begets

others, and the talkers go to telling stories; which is very good

entertainment in moderation, but is not to be mistaken for that

unwearying flow of argument, quaint remark, humorous color, and

sprightly interchange of sentiments and opinions, called

conversation.

The reader will perceive that all hope is gone here of deciding

whether Herbert could have written Tennyson's poems, or whether

Tennyson could have dug as much money out of the Heliogabalus Lode as

Herbert did. The more one sees of life, I think the impression

deepens that men, after all, play about the parts assigned them,

according to their mental and moral gifts, which are limited and

preordained, and that their entrances and exits are governed by a law

no less certain because it is hidden. Perhaps nobody ever

accomplishes all that he feels lies in him to do; but nearly every

one who tries his powers touches the walls of his being occasionally,

and learns about how far to attempt to spring. There are no

impossibilities to youth and inexperience; but when a person has

tried several times to reach high C and been coughed down, he is

quite content to go down among the chorus. It is only the fools who

keep straining at high C all their lives.

Mandeville here began to say that that reminded him of something that

happened when he was on the

But Herbert cut in with the observation that no matter what a man's

single and several capacities and talents might be, he is controlled

by his own mysterious individuality, which is what metaphysicians

call the substance, all else being the mere accidents of the man.

And this is the reason that we cannot with any certainty tell what

any person will do or amount to, for, while we know his talents and

abilities, we do not know the resulting whole, which is he himself.

THE FIRE-TENDER. So if you could take all the first-class qualities

that we admire in men and women, and put them together into one

being, you wouldn't be sure of the result?

“It is fortunate that each generation does not comprehend its own ignorance. We are thus enabled to call our ancestors barbarous.”

In the old days it would

have been thought unphilosophic as well as effeminate to warm the

meeting-houses artificially. In one house I knew, at least, when it

was proposed to introduce a stove to take a little of the chill from

the Sunday services, the deacons protested against the innovation.

They said that the stove might benefit those who sat close to it, but

it would drive all the cold air to the other parts of the church, and

freeze the people to death; it was cold enough now around the edges.

Blessed days of ignorance and upright living! Sturdy men who served

God by resolutely sitting out the icy hours of service, amid the

rattling of windows and the carousal of winter in the high, windswept

galleries! Patient women, waiting in the chilly house for

consumption to pick out his victims, and replace the color of youth

and the flush of devotion with the hectic of disease! At least, you

did not doze and droop in our over-heated edifices, and die of

vitiated air and disregard of the simplest conditions of organized

life. It is fortunate that each generation does not comprehend its

own ignorance. We are thus enabled to call our ancestors barbarous.

It is something also that each age has its choice of the death it

will die. Our generation is most ingenious. From our public

assembly-rooms and houses we have almost succeeded in excluding pure

air. It took the race ages to build dwellings that would keep out

rain; it has taken longer to build houses air-tight, but we are on

the eve of success. We are only foiled by the ill-fitting, insincere

work of the builders, who build for a day, and charge for all time.

II

When the fire on the hearth has blazed up and then settled into

steady radiance, talk begins. There is no place like the chimney-

corner for confidences; for picking up the clews of an old

friendship; for taking note where one's self has drifted, by

comparing ideas and prejudices with the intimate friend of years ago,

whose course in life has lain apart from yours. No stranger puzzles

you so much as the once close friend, with whose thinking and

associates you have for years been unfamiliar. Life has come to mean

this and that to you; you have fallen into certain habits of thought;

for you the world has progressed in this or that direction; of

certain results you feel very sure; you have fallen into harmony with

your surroundings; you meet day after day people interested in the

things that interest you; you are not in the least opinionated, it is

simply your good fortune to look upon the affairs of the world from

the right point of view.

“There is nothing that disgusts a man like getting beaten at chess by a woman”

Usually she flatters

him, but she has the means of pricking clear through his hide on

occasion. It is the great secret of her power to have him think that

she thoroughly believes in him.

THE YOUNG LADY STAYING WITH Us. And you call this hypocrisy? I have

heard authors, who thought themselves sly observers of women, call it

so.

HERBERT. Nothing of the sort. It is the basis on which society

rests, the conventional agreement. If society is about to be

overturned, it is on this point. Women are beginning to tell men

what they really think of them; and to insist that the same relations

of downright sincerity and independence that exist between men shall

exist between women and men. Absolute truth between souls, without

regard to sex, has always been the ideal life of the poets.

THE MISTRESS. Yes; but there was never a poet yet who would bear to

have his wife say exactly what she thought of his poetry, any more

than be would keep his temper if his wife beat him at chess; and

there is nothing that disgusts a man like getting beaten at chess by

a woman.

HERBERT. Well, women know how to win by losing. I think that the

reason why most women do not want to take the ballot and stand out in

the open for a free trial of power, is that they are reluctant to

change the certain domination of centuries, with weapons they are

perfectly competent to handle, for an experiment. I think we should

be better off if women were more transparent, and men were not so

systematically puffed up by the subtle flattery which is used to

control them.

MANDEVILLE. Deliver me from transparency. When a woman takes that

guise, and begins to convince me that I can see through her like a

ray of light, I must run or be lost. Transparent women are the truly

dangerous. There was one on ship-board [Mandeville likes to say

that; he has just returned from a little tour in Europe, and he quite

often begins his remarks with "on the ship going over; "the Young

Lady declares that he has a sort of roll in his chair, when he says

it, that makes her sea-sick] who was the most innocent, artless,

guileless, natural bunch of lace and feathers you ever saw; she was

all candor and helplessness and dependence; she sang like a

nightingale, and talked like a nun.

“Politics makes strange bedfellows”

Some of them had blossomed; and a few had gone

so far as to bear ripe berries,--long, pear-shaped fruit, hanging

like the ear-pendants of an East Indian bride. I could not but

admire the persistence of these zealous plants, which seemed

determined to propagate themselves both by seeds and roots, and make

sure of immortality in some way. Even the Colfax variety was as

ambitious as the others. After having seen the declining letter of

Mr. Colfax, I did not suppose that this vine would run any more, and

intended to root it out. But one can never say what these

politicians mean; and I shall let this variety grow until after the

next election, at least; although I hear that the fruit is small, and

rather sour. If there is any variety of strawberries that really

declines to run, and devotes itself to a private life of fruit-

bearing, I should like to get it. I may mention here, since we are

on politics, that the Doolittle raspberries had sprawled all over the

strawberry-bed's: so true is it that politics makes strange

bedfellows.

But another enemy had come into the strawberries, which, after all

that has been said in these papers, I am almost ashamed to mention.

But does the preacher in the pulpit, Sunday after Sunday, year after

year, shrink from speaking of sin? I refer, of course, to the

greatest enemy of mankind, " p-sl-y." The ground was carpeted with

it. I should think that this was the tenth crop of the season; and

it was as good as the first. I see no reason why our northern soil

is not as prolific as that of the tropics, and will not produce as

many crops in the year. The mistake we make is in trying to force

things that are not natural to it. I have no doubt that, if we turn

our attention to "pusley," we can beat the world.

I had no idea, until recently, how generally this simple and thrifty

plant is feared and hated. Far beyond what I had regarded as the

bounds of civilization, it is held as one of the mysteries of a

fallen world; accompanying the home missionary on his wanderings, and

preceding the footsteps of the Tract Society.

“People always overdo the matter when they attempt deception.”

Considerable cholera is the only thing that would let

my apples and pears ripen. Of course I do not care for the fruit;

but I do not want to take the responsibility of letting so much

"life-matter," full of crude and even wicked vegetable-human

tendencies, pass into the composition of the neighbors' children,

some of whom may be as immortal as snake-grass. There ought to be a

public meeting about this, and resolutions, and perhaps a clambake.

At least, it ought to be put into the catechism, and put in strong.

TENTH WEEK

I think I have discovered the way to keep peas from the birds. I

tried the scarecrow plan, in a way which I thought would outwit the

shrewdest bird. The brain of the bird is not large; but it is all

concentrated on one object, and that is the attempt to elude the

devices of modern civilization which injure his chances of food. I

knew that, if I put up a complete stuffed man, the bird would detect

the imitation at once: the perfection of the thing would show him

that it was a trick. People always overdo the matter when they

attempt deception. I therefore hung some loose garments, of a bright

color, upon a rake-head, and set them up among the vines. The

supposition was, that the bird would think there was an effort to

trap him, that there was a man behind, holding up these garments, and

would sing, as he kept at a distance, "You can't catch me with any

such double device." The bird would know, or think he knew, that I

would not hang up such a scare, in the expectation that it would pass

for a man, and deceive a bird; and he would therefore look for a

deeper plot. I expected to outwit the bird by a duplicity that was

simplicity itself I may have over-calculated the sagacity and

reasoning power of the bird. At any rate, I did over-calculate the

amount of peas I should gather.

But my game was only half played. In another part of the garden were

other peas, growing and blowing. To-these I took good care not to

attract the attention of the bird by any scarecrow whatever! I left

the old scarecrow conspicuously flaunting above the old vines; and by

this means I hope to keep the attention of the birds confined to that

side of the garden.

“Politics makes strange bed-fellows.”

Some of them had blossomed; and a few had gone

so far as to bear ripe berries,--long, pear-shaped fruit, hanging

like the ear-pendants of an East Indian bride. I could not but

admire the persistence of these zealous plants, which seemed

determined to propagate themselves both by seeds and roots, and make

sure of immortality in some way. Even the Colfax variety was as

ambitious as the others. After having seen the declining letter of

Mr. Colfax, I did not suppose that this vine would run any more, and

intended to root it out. But one can never say what these

politicians mean; and I shall let this variety grow until after the

next election, at least; although I hear that the fruit is small, and

rather sour. If there is any variety of strawberries that really

declines to run, and devotes itself to a private life of fruit-

bearing, I should like to get it. I may mention here, since we are

on politics, that the Doolittle raspberries had sprawled all over the

strawberry-bed's: so true is it that politics makes strange

bedfellows.

But another enemy had come into the strawberries, which, after all

that has been said in these papers, I am almost ashamed to mention.

But does the preacher in the pulpit, Sunday after Sunday, year after

year, shrink from speaking of sin? I refer, of course, to the

greatest enemy of mankind, " p-sl-y." The ground was carpeted with

it. I should think that this was the tenth crop of the season; and

it was as good as the first. I see no reason why our northern soil

is not as prolific as that of the tropics, and will not produce as

many crops in the year. The mistake we make is in trying to force

things that are not natural to it. I have no doubt that, if we turn

our attention to "pusley," we can beat the world.

I had no idea, until recently, how generally this simple and thrifty

plant is feared and hated. Far beyond what I had regarded as the

bounds of civilization, it is held as one of the mysteries of a

fallen world; accompanying the home missionary on his wanderings, and

preceding the footsteps of the Tract Society.

“To own a bit of ground, to scratch it with a hoe, to plant seeds, and watch the renewal of life - this is the commonest delight of the race, the most satisfactory thing a man can do”

What might have become

of the garden, if your advice had been followed, a good Providence

only knows; but I never worked there without a consciousness that you

might at any moment come down the walk, under the grape-arbor,

bestowing glances of approval, that were none the worse for not being

critical; exercising a sort of superintendence that elevated

gardening into a fine art; expressing a wonder that was as

complimentary to me as it was to Nature; bringing an atmosphere which

made the garden a region of romance, the soil of which was set apart

for fruits native to climes unseen. It was this bright presence that

filled the garden, as it did the summer, with light, and now leaves

upon it that tender play of color and bloom which is called among the

Alps the after-glow.

NOOK FARM, HARTFORD, October, 1870

C. D. W.

PRELIMINARY

The love of dirt is among the earliest of passions, as it is the

latest. Mud-pies gratify one of our first and best instincts. So

long as we are dirty, we are pure. Fondness for the ground comes

back to a man after he has run the round of pleasure and business,

eaten dirt, and sown wild-oats, drifted about the world, and taken

the wind of all its moods. The love of digging in the ground (or of

looking on while he pays another to dig) is as sure to come back to

him as he is sure, at last, to go under the ground, and stay there.

To own a bit of ground, to scratch it with a hoe, to plant seeds and

watch, their renewal of life, this is the commonest delight of the

race, the most satisfactory thing a man can do. When Cicero writes

of the pleasures of old age, that of agriculture is chief among them:

"Venio nunc ad voluptates agricolarum, quibus ego incredibiliter

delector: quae nec ulla impediuntur senectute, et mihi ad sapientis

vitam proxime videntur accedere." (I am driven to Latin because New

York editors have exhausted the English language in the praising of

spring, and especially of the month of May.)

Let us celebrate the soil. Most men toil that they may own a piece

of it; they measure their success in life by their ability to buy it.

It is alike the passion of the parvenu and the pride of the

aristocrat. Broad acres are a patent of nobility; and no man but

feels more, of a man in the world if he have a bit of ground that he

can call his own. However small it is on the surface, it is four

thousand miles deep; and that is a very handsome property. And there

is a great pleasure in working in the soil, apart from the ownership

of it. The man who has planted a garden feels that he has done

something for the good of the World.

“A cynic might suggest as the motto of modern life this simple legend - Just as good as the real”

This age, which imitates everything, even

to the virtues of our ancestors, has invented a fireplace, with

artificial, iron, or composition logs in it, hacked and painted, in

which gas is burned, so that it has the appearance of a wood-fire.

This seems to me blasphemy. Do you think a cat would lie down before

it? Can you poke it? If you can't poke it, it is a fraud. To poke

a wood-fire is more solid enjoyment than almost anything else in the

world. The crowning human virtue in a man is to let his wife poke

the fire. I do not know how any virtue whatever is possible over an

imitation gas-log. What a sense of insincerity the family must have,

if they indulge in the hypocrisy of gathering about it. With this

center of untruthfulness, what must the life in the family be?

Perhaps the father will be living at the rate of ten thousand a year

on a salary of four thousand; perhaps the mother, more beautiful and

younger than her beautified daughters, will rouge; perhaps the young

ladies will make wax-work. A cynic might suggest as the motto of

modern life this simple legend,--"just as good as the real." But I am

not a cynic, and I hope for the rekindling of wood-fires, and a

return of the beautiful home light from them. If a wood-fire is a

luxury, it is cheaper than many in which we indulge without thought,

and cheaper than the visits of a doctor, made necessary by the want

of ventilation of the house. Not that I have anything against

doctors; I only wish, after they have been to see us in a way that

seems so friendly, they had nothing against us.

My fireplace, which is deep, and nearly three feet wide, has a broad

hearthstone in front of it, where the live coals tumble down, and a

pair of gigantic brass andirons. The brasses are burnished, and

shine cheerfully in the firelight, and on either side stand tall

shovel and tongs, like sentries, mounted in brass. The tongs, like

the two-handed sword of Bruce, cannot be wielded by puny people. We

burn in it hickory wood, cut long. We like the smell of this

aromatic forest timber, and its clear flame. The birch is also a

sweet wood for the hearth, with a sort of spiritual flame and an even

temper,--no snappishness.

“We are half ruined by conformity, but we should be wholly ruined without it”

I admire the force by which it

compacts its crisp leaves into a solid head. The secret of it would

be priceless to the world. We should see less expansive foreheads

with nothing within. Even the largest cabbages are not always the

best. But I mention these things, not from any sympathy I have with

the vegetables named, but to show how hard it is to go contrary to

the expectations of society. Society expects every man to have

certain things in his garden. Not to raise cabbage is as if one had

no pew in church. Perhaps we shall come some day to free churches

and free gardens; when I can show my neighbor through my tired

garden, at the end of the season, when skies are overcast, and brown

leaves are swirling down, and not mind if he does raise his eyebrows

when he observes, "Ah! I see you have none of this, and of that." At

present we want the moral courage to plant only what we need; to

spend only what will bring us peace, regardless of what is going on

over the fence. We are half ruined by conformity; but we should be

wholly ruined without it; and I presume I shall make a garden next

year that will be as popular as possible.

And this brings me to what I see may be a crisis in life. I begin to

feel the temptation of experiment. Agriculture, horticulture,

floriculture,--these are vast fields, into which one may wander away,

and never be seen more. It seemed to me a very simple thing, this

gardening; but it opens up astonishingly. It is like the infinite

possibilities in worsted-work. Polly sometimes says to me, "I wish

you would call at Bobbin's, and match that skein of worsted for me,

when you are in town." Time was, I used to accept such a commission

with alacrity and self-confidence. I went to Bobbin's, and asked one

of his young men, with easy indifference, to give me some of that.

The young man, who is as handsome a young man as ever I looked at,

and who appears to own the shop, and whose suave superciliousness

would be worth everything to a cabinet minister who wanted to repel

applicants for place, says, "I have n't an ounce: I have sent to

Paris, and I expect it every day.

“I am convinced that the majority of people would be generous from selfish motives, if they had the opportunity.”

The robin, the most knowing and

greedy bird out of paradise (I trust he will always be kept out), has

discovered that the grape-crop is uncommonly good, and has come back,

with his whole tribe and family, larger than it was in pea-time. He

knows the ripest bunches as well as anybody, and tries them all. If

he would take a whole bunch here and there, say half the number, and

be off with it, I should not so much care. But he will not. He

pecks away at all the bunches, and spoils as many as he can. It is

time he went south.

There is no prettier sight, to my eye, than a gardener on a ladder in

his grape-arbor, in these golden days, selecting the heaviest

clusters of grapes, and handing them down to one and another of a

group of neighbors and friends, who stand under the shade of the

leaves, flecked with the sunlight, and cry, "How sweet!" "What nice

ones!" and the like,--remarks encouraging to the man on the ladder.

It is great pleasure to see people eat grapes.

Moral Truth. --I have no doubt that grapes taste best in other

people's mouths. It is an old notion that it is easier to be

generous than to be stingy. I am convinced that the majority of

people would be generous from selfish motives, if they had the

opportunity.

Philosophical Observation. --Nothing shows one who his friends are

like prosperity and ripe fruit. I had a good friend in the country,

whom I almost never visited except in cherry-time. By your fruits

you shall know them.

SEVENTEENTH WEEK

I like to go into the garden these warm latter days, and muse. To

muse is to sit in the sun, and not think of anything. I am not sure

but goodness comes out of people who bask in the sun, as it does out

of a sweet apple roasted before the fire. The late September and

October sun of this latitude is something like the sun of extreme

Lower Italy: you can stand a good deal of it, and apparently soak a

winter supply into the system. If one only could take in his winter

fuel in this way! The next great discovery will, very likely, be the

conservation of sunlight. In the correlation of forces, I look to

see the day when the superfluous sunshine will be utilized; as, for

instance, that which has burned up my celery this year will be

converted into a force to work the garden.

“Public opinion is stronger than the legislature, and nearly as strong as the ten commandments”

It is good for the mind, unless they are too small

(as many of mine are), when it begets a want of gratitude to the

bountiful earth. What small potatoes we all are, compared with what

we might be! We don't plow deep enough, any of us, for one thing. I

shall put in the plow next year, and give the tubers room enough. I

think they felt the lack of it this year: many of them seemed ashamed

to come out so small. There is great pleasure in turning out the

brown-jacketed fellows into the sunshine of a royal September day,

and seeing them glisten as they lie thickly strewn on the warm soil.

Life has few such moments. But then they must be picked up. The

picking-up, in this world, is always the unpleasant part of it.

SIXTEENTH WEEK

I do not hold myself bound to answer the question, Does gardening

pay? It is so difficult to define what is meant by paying. There is

a popular notion that, unless a thing pays, you had better let it

alone; and I may say that there is a public opinion that will not let

a man or woman continue in the indulgence of a fancy that does not

pay. And public opinion is stronger than the legislature, and nearly

as strong as the ten commandments: I therefore yield to popular

clamor when I discuss the profit of my garden.

As I look at it, you might as well ask, Does a sunset pay? I know

that a sunset is commonly looked on as a cheap entertainment; but it

is really one of the most expensive. It is true that we can all have

front seats, and we do not exactly need to dress for it as we do for

the opera; but the conditions under which it is to be enjoyed are

rather dear. Among them I should name a good suit of clothes,

including some trifling ornament,--not including back hair for one

sex, or the parting of it in the middle for the other. I should add

also a good dinner, well cooked and digestible; and the cost of a

fair education, extended, perhaps, through generations in which

sensibility and love of beauty grew. What I mean is, that if a man

is hungry and naked, and half a savage, or with the love of beauty

undeveloped in him, a sunset is thrown away on him : so that it

appears that the conditions of the enjoyment of a sunset are as

costly as anything in our civilization.

“How many wars have been caused by fits of indigestion, and how many more dynasties have been upset by the love of woman than by the hate of man”

The

gardener needs all these consolations of a high philosophy.

EIGHTEENTH WEEK

Regrets are idle; yet history is one long regret. Everything might

have turned out so differently! If Ravaillac had not been imprisoned

for debt, he would not have stabbed Henry of Navarre. If William of

Orange had escaped assassination by Philip's emissaries; if France

had followed the French Calvin, and embraced Protestant Calvinism, as

it came very near doing towards the end of the sixteenth century; if

the Continental ammunition had not given out at Bunker's Hill; if

Blucher had not "come up" at Waterloo,--the lesson is, that things do

not come up unless they are planted. When you go behind the

historical scenery, you find there is a rope and pulley to effect

every transformation which has astonished you. It was the rascality

of a minister and a contractor five years before that lost the

battle; and the cause of the defeat was worthless ammunition. I

should like to know how many wars have been caused by fits of

indigestion, and how many more dynasties have been upset by the love

of woman than by the hate of man. It is only because we are ill

informed that anything surprises us; and we are disappointed because

we expect that for which we have not provided.

I had too vague expectations of what my garden would do of itself. A

garden ought to produce one everything,--just as a business ought to

support a man, and a house ought to keep itself. We had a convention

lately to resolve that the house should keep itself; but it won't.

There has been a lively time in our garden this summer; but it seems

to me there is very little to show for it. It has been a terrible

campaign; but where is the indemnity? Where are all "sass" and

Lorraine? It is true that we have lived on the country; but we

desire, besides, the fruits of the war. There are no onions, for one

thing. I am quite ashamed to take people into my garden, and have

them notice the absence of onions. It is very marked. In onion is

strength; and a garden without it lacks flavor. The onion in its

satin wrappings is among the most beautiful of vegetables; and it is

the only one that represents the essence of things.

“There was never a nation great until it came to the knowledge that it had nowhere in the world to go for help”

And there could

be no greater calamity to Canada, to the United States, to the

English-speaking interest in the world, than a collision. Nothing is

to be more dreaded for its effect upon the morals of the people of the

United States than any war with any taint of conquest in it.

There is, no doubt, with many, an honest preference for the colonial

condition. I have heard this said:

"We have the best government in the world, a responsible government,

with entire local freedom. England exercises no sort of control; we are

as free as a nation can he. We have in the representative of the Crown a

certain conservative tradition, and it only costs us ten thousand pounds

a year. We are free, we have little expense, and if we get into any

difficulty there is the mighty power of Great Britain behind us!" It

is as if one should say in life, I have no responsibilities; I have a

protector. Perhaps as a "rebel," I am unable to enter into the colonial

state of mind. But the boy is never a man so long as he is dependent.

There was never a nation great until it came to the knowledge that it

had nowhere in the world to go for help.

In Canada to-dav there is a growing feeling for independence; very

little, taking the whole mass, for annexation. Put squarely to a popular

vote, it would make little show in the returns. Among the minor causes

of reluctance to a union are distrust of the Government of the United

States, coupled with the undoubted belief that Canada has the better

government; dislike of our quadrennial elections; the want of a

system of civil service, with all the turmoil of our constant official

overturning; dislike of our sensational and irresponsible journalism,

tending so often to recklessness; and dislike also, very likely, of

the very assertive spirit which has made us so rapidly subdue our

continental possessions.

But if one would forecast the future of Canada, he needs to take a wider

view than personal preferences or the agitations of local parties. The

railway development, the Canadian Pacific alone, has changed within five

years the prospects of the political situation. It has brought together

the widely separated provinces, and has given a new impulse to the

sentiment of nationality.

“The thing generally raised on city land is taxes”

Shall I turn into merchandise

the red strawberry, the pale green pea, the high-flavored raspberry,

the sanguinary beet, that love-plant the tomato, and the corn which

did not waste its sweetness on the desert air, but, after flowing in

a sweet rill through all our summer life, mingled at last with the

engaging bean in a pool of succotash? Shall I compute in figures

what daily freshness and health and delight the garden yields, let

alone the large crop of anticipation I gathered as soon as the first

seeds got above ground? I appeal to any gardening man of sound mind,

if that which pays him best in gardening is not that which he cannot

show in his trial-balance. Yet I yield to public opinion, when I

proceed to make such a balance; and I do it with the utmost

confidence in figures.

I select as a representative vegetable, in order to estimate the cost

of gardening, the potato. In my statement, I shall not include the

interest on the value of the land. I throw in the land, because it

would otherwise have stood idle: the thing generally raised on city

land is taxes. I therefore make the following statement of the cost

and income of my potato-crop, a part of it estimated in connection

with other garden labor. I have tried to make it so as to satisfy

the income-tax collector:--

Plowing.......................................$0.50

Seed..........................................$1.50

Manure........................................ 8.00

Assistance in planting and digging, 3 days.... 6.75

Labor of self in planting, hoeing, digging,

picking up, 5 days at 17 cents........... 0.85

_____

Total Cost................$17.60

Two thousand five hundred mealy potatoes,

at 2 cents..............................$50.00

Small potatoes given to neighbor's pig....... .50

Total return..............$50.50

Balance, profit in cellar......$32.90

Some of these items need explanation. I have charged nothing for my

own time waiting for the potatoes to grow.

“No one can sincerely try to help another without helping himself.”

Whatever we may say, we all of us like distinction; and probably

there is no more subtle flattery than that conveyed in the whisper,

"That's he," "That's she."

There used to be a society for ameliorating the condition of the

Jews; but they were found to be so much more adept than other people

in ameliorating their own condition that I suppose it was given up.

Mandeville says that to his knowledge there are a great many people

who get up ameliorating enterprises merely to be conspicuously busy

in society, or to earn a little something in a good cause. They seem

to think that the world owes them a living because they are

philanthropists. In this Mandeville does not speak with his usual

charity. It is evident that there are Jews, and some Gentiles, whose

condition needs ameliorating, and if very little is really

accomplished in the effort for them, it always remains true that the

charitable reap a benefit to themselves. It is one of the beautiful

compensations of this life that no one can sincerely try to help

another without helping himself

OUR NEXT-DOOR NEIGHBOR. Why is it that almost all philanthropists

and reformers are disagreeable?

I ought to explain who our next-door neighbor is. He is the person

who comes in without knocking, drops in in the most natural way, as

his wife does also, and not seldom in time to take the after-dinner

cup of tea before the fire. Formal society begins as soon as you

lock your doors, and only admit visitors through the media of bells

and servants. It is lucky for us that our next-door neighbor is

honest.

THE PARSON. Why do you class reformers and philanthropists together?

Those usually called reformers are not philanthropists at all. They

are agitators. Finding the world disagreeable to themselves, they

wish to make it as unpleasant to others as possible.

MANDEVILLE. That's a noble view of your fellow-men.

OUR NEXT DOOR. Well, granting the distinction, why are both apt to

be unpleasant people to live with?

THE PARSON. As if the unpleasant people who won't mind their own

business were confined to the classes you mention!

“Mud-pies gratify one of our first and best instincts. So long as we are dirty, we are pure.”

There was almost nothing

that you did not wish to know; and this, added to what I wished to

know, made a boundless field for discovery. What might have become

of the garden, if your advice had been followed, a good Providence

only knows; but I never worked there without a consciousness that you

might at any moment come down the walk, under the grape-arbor,

bestowing glances of approval, that were none the worse for not being

critical; exercising a sort of superintendence that elevated

gardening into a fine art; expressing a wonder that was as

complimentary to me as it was to Nature; bringing an atmosphere which

made the garden a region of romance, the soil of which was set apart

for fruits native to climes unseen. It was this bright presence that

filled the garden, as it did the summer, with light, and now leaves

upon it that tender play of color and bloom which is called among the

Alps the after-glow.

NOOK FARM, HARTFORD, October, 1870

C. D. W.

PRELIMINARY

The love of dirt is among the earliest of passions, as it is the

latest. Mud-pies gratify one of our first and best instincts. So

long as we are dirty, we are pure. Fondness for the ground comes

back to a man after he has run the round of pleasure and business,

eaten dirt, and sown wild-oats, drifted about the world, and taken

the wind of all its moods. The love of digging in the ground (or of

looking on while he pays another to dig) is as sure to come back to

him as he is sure, at last, to go under the ground, and stay there.

To own a bit of ground, to scratch it with a hoe, to plant seeds and

watch, their renewal of life, this is the commonest delight of the

race, the most satisfactory thing a man can do. When Cicero writes

of the pleasures of old age, that of agriculture is chief among them:

"Venio nunc ad voluptates agricolarum, quibus ego incredibiliter

delector: quae nec ulla impediuntur senectute, et mihi ad sapientis

vitam proxime videntur accedere." (I am driven to Latin because New

York editors have exhausted the English language in the praising of

spring, and especially of the month of May.)

Let us celebrate the soil.