“Success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life... as by the obstacles which he has overcome while trying to succeed.”

Many children

of the tenderest years were compelled then, as is now true I fear, in

most coal-mining districts, to spend a large part of their lives in

these coal-mines, with little opportunity to get an education; and, what

is worse, I have often noted that, as a rule, young boys who begin life

in a coal-mine are often physically and mentally dwarfed. They soon lose

ambition to do anything else than to continue as a coal-miner.

In those days, and later as a young man, I used to try to picture in my

imagination the feelings and ambitions of a white boy with absolutely

no limit placed upon his aspirations and activities. I used to envy

the white boy who had no obstacles placed in the way of his becoming a

Congressman, Governor, Bishop, or President by reason of the accident of

his birth or race. I used to picture the way that I would act under such

circumstances; how I would begin at the bottom and keep rising until I

reached the highest round of success.

In later years, I confess that I do not envy the white boy as I once

did. I have learned that success is to be measured not so much by the

position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has

overcome while trying to succeed. Looked at from this standpoint, I

almost reached the conclusion that often the Negro boy's birth and

connection with an unpopular race is an advantage, so far as real life

is concerned. With few exceptions, the Negro youth must work harder and

must perform his tasks even better than a white youth in order to secure

recognition. But out of the hard and unusual struggle through which he

is compelled to pass, he gets a strength, a confidence, that one misses

whose pathway is comparatively smooth by reason of birth and race.

From any point of view, I had rather be what I am, a member of the Negro

race, than be able to claim membership with the most favoured of any

other race. I have always been made sad when I have heard members of any

race claiming rights or privileges, or certain badges of distinction,

on the ground simply that they were members of this or that race,

regardless of their own individual worth or attainments. I have been

made to feel sad for such persons because I am conscious of the fact

that mere connection with what is known as a superior race will not

permanently carry an individual forward unless he has individual worth,

and mere connection with what is regarded as an inferior race will not

finally hold an individual back if he possesses intrinsic, individual

merit.

All the bank

presidents in the city of New York were having meetings every night to

find out how well they were succeeding in keeping their institutions

solvent. At one of these meetings, after a critical day in the most

trying period of the panic, when some men reported that they had lost

money during that day, and others that so much money had been withdrawn

from their banks during the day that if there were another like it they

did not see how they could stand the strain, William Taylor reported

that money had been added to the deposits of his bank that day instead

of being withdrawn.

What was behind all this? William Taylor had learned in early life

that it did not pay to be dishonest, but that it paid to be honest

with all his depositors and with all persons who did business with

his bank. When other people were failing in all parts of the country,

the evidence of this man's character, his regard for truth and honest

dealing, caused money to come into his bank when it was being withdrawn

from others.

Character is a power. If you want to be powerful in the world, if you

want to be strong, influential and useful, you can be so in no better

way than by having strong character; but you cannot have a strong

character if you yield to the temptations about which I have been

speaking.

Some one asked, some time ago, what it was that gave such a power to

the sermons of the late Dr. John Hall. In the usual sense he was not

a powerful speaker; but everything he said carried conviction with

it. The explanation was that the character of the man was behind the

sermon. You may go out and make great speeches, you may write books or

addresses which are great literature, but unless you have character

behind what you say and write, it will amount to nothing; it will all

go to the winds.

I leave this question with you, then. When you are tempted to do what

your conscience tells you is not right, ask yourself: "Will it pay me

to do this thing which I know is not right?" Go to the penitentiary.

Ask the people there who have failed, who have made mistakes, why they

are there, and in every case they will tell you that they are there

because they yielded to temptation, because they did not ask themselves

the question: "Will it pay?

“Nothing ever comes to one, that is worth having, except as a result of hard work.”

If the institution had been officered by white

persons, and had failed, it would have injured the cause of Negro

education; but I knew that the failure of our institution, officered

by Negroes, would not only mean the loss of a school, but would cause

people, in a large degree, to lose faith in the ability of the entire

race. The receipt of this draft for ten thousand dollars, under all

these circumstances, partially lifted a burden that had been pressing

down upon me for days.

From the beginning of our work to the present I have always had the

feeling, and lose no opportunity to impress our teachers with the same

idea, that the school will always be supported in proportion as the

inside of the institution is kept clean and pure and wholesome.

The first time I ever saw the late Collis P. Huntington, the great

railroad man, he gave me two dollars for our school. The last time I saw

him, which was a few months before he died, he gave me fifty thousand

dollars toward our endowment fund. Between these two gifts there were

others of generous proportions which came every year from both Mr. and

Mrs. Huntington.

Some people may say that it was Tuskegee's good luck that brought to us

this gift of fifty thousand dollars. No, it was not luck. It was hard

work. Nothing ever comes to me, that is worth having, except as the

result of hard work. When Mr. Huntington gave me the first two dollars,

I did not blame him for not giving me more, but made up my mind that

I was going to convince him by tangible results that we were worthy of

larger gifts. For a dozen years I made a strong effort to convince Mr.

Huntington of the value of our work. I noted that just in proportion as

the usefulness of the school grew, his donations increased. Never did

I meet an individual who took a more kindly and sympathetic interest in

our school than did Mr. Huntington. He not only gave money to us, but

took time in which to advise me, as a father would a son, about the

general conduct of the school.

More than once I have found myself in some pretty tight places while

collecting money in the North. The following incident I have never

related but once before, for the reason that I feared that people would

not believe it. One morning I found myself in Providence, Rhode Island,

without a cent of money with which to buy breakfast. In crossing the

street to see a lady from whom I hoped to get some money, I found a

bright new twenty-five-cent piece in the middle of the street track.

“Few things can help an individual more than to place responsibility on him, and to let him know that you trust him.”

From the first I have sought to impress the students with the idea that

Tuskegee is not my institution, or that of the officers, but that it is

their institution, and that they have as much interest in it as any of

the trustees or instructors. I have further sought to have them feel

that I am at the institution as their friend and adviser, and not as

their overseer. It has been my aim to have them speak with directness

and frankness about anything that concerns the life of the school.

Two or three times a year I ask the students to write me a letter

criticising or making complaints or suggestions about anything connected

with the institution. When this is not done, I have them meet me in the

chapel for a heart-to-heart talk about the conduct of the school. There

are no meetings with our students that I enjoy more than these, and none

are more helpful to me in planning for the future. These meetings, it

seems to me, enable me to get at the very heart of all that concerns the

school. Few things help an individual more than to place responsibility

upon him, and to let him know that you trust him. When I have read of

labour troubles between employers and employees, I have often thought

that many strikes and similar disturbances might be avoided if

the employers would cultivate the habit of getting nearer to their

employees, of consulting and advising with them, and letting them feel

that the interests of the two are the same. Every individual responds to

confidence, and this is not more true of any race than of the Negroes.

Let them once understand that you are unselfishly interested in them,

and you can lead them to any extent.

It was my aim from the first at Tuskegee to not only have the buildings

erected by the students themselves, but to have them make their own

furniture as far as was possible. I now marvel at the patience of the

students while sleeping upon the floor while waiting for some kind of a

bedstead to be constructed, or at their sleeping without any kind of a

mattress while waiting for something that looked like a mattress to be

made.

In the early days we had very few students who had been used to handling

carpenters' tools, and the bedsteads made by the students then were very

rough and very weak.

“No man, who continues to add something to the material, intellectual and moral well-being of the place in which he lives, is left long without proper reward.”

Few people ever stopped, I found, when looking

at his pictures, to inquire whether Mr. Tanner was a Negro painter, a

French painter, or a German painter. They simply knew that he was able

to produce something which the world wanted--a great painting--and the

matter of his colour did not enter into their minds. When a Negro girl

learns to cook, to wash dishes, to sew, or write a book, or a Negro boy

learns to groom horses, or to grow sweet potatoes, or to produce butter,

or to build a house, or to be able to practise medicine, as well or

better than some one else, they will be rewarded regardless of race or

colour. In the long run, the world is going to have the best, and any

difference in race, religion, or previous history will not long keep the

world from what it wants.

I think that the whole future of my race hinges on the question as to

whether or not it can make itself of such indispensable value that the

people in the town and the state where we reside will feel that our

presence is necessary to the happiness and well-being of the community.

No man who continues to add something to the material, intellectual,

and moral well-being of the place in which he lives is long left without

proper reward. This is a great human law which cannot be permanently

nullified.

The love of pleasure and excitement which seems in a large measure to

possess the French people impressed itself upon me. I think they are

more noted in this respect than is true of the people of my own race. In

point of morality and moral earnestness I do not believe that the French

are ahead of my own race in America. Severe competition and the great

stress of life have led them to learn to do things more thoroughly and

to exercise greater economy; but time, I think, will bring my race to

the same point. In the matter of truth and high honour I do not believe

that the average Frenchman is ahead of the American Negro; while so far

as mercy and kindness to dumb animals go, I believe that my race is far

ahead. In fact, when I left France, I had more faith in the future of

the black man in America than I had ever possessed.

From Paris we went to London, and reached there early in July, just

about the height of the London social season.

“Excellence is to do a common thing in an uncommon way.”

“The world cares very little about what a man or woman knows; it is what a man or woman is able to do that counts.”

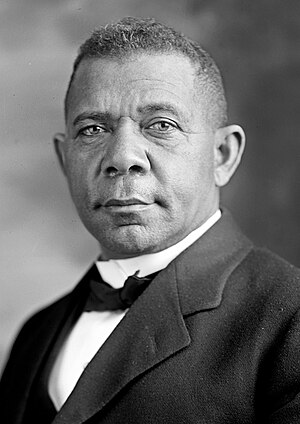

“Most leaders spend time trying to get others to think highlyof them, when instead they should try to get their people tothink more highly of themselves.Its wonderful when the people believe in their leader.Its more wonderful when the leader believes in their people!You cant hold a man down withoutstaying down with him. Booker T. Washington”

“I shall allow no man to belittle my soul by making me hate him.”

“Character, not circumstances, make the man.”

“I will permit no man to narrow and degrade my soul by making me hate him.”

“If you want to lift yourself up, lift up someone else.”

“Dignify and glorify common labor. It is at the bottom of life that we must begin, not at the top.”

“There are two ways of exerting ones strength: one is pushing down, the other is pulling up.”

“Associate yourself with people of good quality, for it is better to be alone than in bad company.”

“You cant hold a man down without staying down with him.”

“One man cannot hold another man down in the ditch without remaining down in the ditch with him.”

“Success in life is founded upon attention to the small things rather than to the large things; to the every day things nearest to us rather than to the things that are remote and uncommon.”

“At the bottom of education, at the bottom of politics, even at the bottom of religion, there must be for our race economic independence.”

“I believe that any mans life will be filled with constant and unexpected encouragement, if he makes up his mind to do his level best each day, and as nearly as possible reaching the high water mark of pure and useful living.”