“She knew how to allure by denying, and to make the gift rich by delaying it.”

Then she found herself possessed of money,

certainly; of wit,--as she believed; and of a something in her

personal appearance which, as she plainly told herself, she might

perhaps palm off upon the world as beauty. She was a woman who did

not flatter herself, who did not strongly believe in herself, who

could even bring herself to wonder that men and women in high

position should condescend to notice such a one as her. With all her

ambition, there was a something of genuine humility about her; and

with all the hardness she had learned there was a touch of womanly

softness which would sometimes obtrude itself upon her heart. When

she found a woman really kind to her, she would be very kind in

return. And though she prized wealth, and knew that her money was her

only rock of strength, she could be lavish with it, as though it were

dirt.

But she was highly ambitious, and she played her game with

great skill and great caution. Her doors were not open to all

callers;--were shut even to some who find but few doors closed

against them;--were shut occasionally to those whom she most

specially wished to see within them. She knew how to allure by

denying, and to make the gift rich by delaying it. We are told by the

Latin proverb that he who gives quickly gives twice; but I say that

she who gives quickly seldom gives more than half. When in the early

spring the Duke of Omnium first knocked at Madame Max Goesler's door,

he was informed that she was not at home. The Duke felt very cross as

he handed his card out from his dark green brougham,--on the panel

of which there was no blazon to tell the owner's rank. He was very

cross. She had told him that she was always at home between four and

six on a Thursday. He had condescended to remember the information,

and had acted upon it,--and now she was not at home! She was not at

home, though he had come on a Thursday at the very hour she had named

to him. Any duke would have been cross, but the Duke of Omnium was

particularly cross. No;--he certainly would give himself no further

trouble by going to the cottage in Park Lane. And yet Madame Max

Goesler had been in her own drawing-room, while the Duke was handing

out his card from the brougham below.

“Nobody holds a good opinion of a man who holds a low opinion of himself”

But although Staveley was himself perfectly indifferent to all the

charms of Miss Furnival, nevertheless he could hardly restrain his

dislike to Lucius Mason, who, as he thought, was disposed to admire

the lady in question. In talking of Lucius to his own family and to

his special friend Graham, he had called him conceited, pedantic,

uncouth, unenglish, and detestable. His own family, that is, his

mother and sister, rarely contradicted him in anything; but Graham

was by no means so cautious, and usually contradicted him in

everything. Indeed, there was no sign of sterling worth so plainly

marked in Staveley's character as the full conviction which he

entertained of the superiority of his friend Felix.

"You are quite wrong about him," Felix had said. "He has not been at

an English school, or English university, and therefore is not like

other young men that you know; but he is, I think, well educated

and clever. As for conceit, what man will do any good who is not

conceited? Nobody holds a good opinion of a man who has a low opinion

of himself."

"All the same, my dear fellow, I do not like Lucius Mason."

"And some one else, if you remember, did not like Dr. Fell."

"And now, good people, what are you all going to do about church?"

said Staveley, while they were still engaged with their rolls and

eggs.

"I shall walk," said the judge.

"And I shall go in the carriage," said the judge's wife.

"That disposes of two; and now it will take half an hour to settle

for the rest. Miss. Furnival, you no doubt will accompany my mother.

As I shall be among the walkers you will see how much I sacrifice by

the suggestion."

It was a mile to the church, and Miss Furnival knew the advantage

of appearing in her seat unfatigued and without subjection to wind,

mud, or rain. "I must confess," she said, "that under all the

circumstances, I shall prefer your mother's company to yours;"

whereupon Staveley, in the completion of his arrangements, assigned

the other places in the carriage to the married ladies of the

company.

“I doubt whether any girl would be satisfied with her lovers mind if she knew the whole of it.”

He was to

return to Guestwick again during this autumn; but, to tell honestly

the truth in the matter, Lily Dale did not think or care very

much for his coming. Girls of nineteen do not care for lovers of

one-and-twenty, unless it be when the fruit has had the advantage of

some forcing apparatus or southern wall.

John Eames's love was still as hot as ever, having been sustained on

poetry, and kept alive, perhaps, by some close confidence in the ears

of a brother clerk; but it is not to be supposed that during these

two years he had been a melancholy lover. It might, perhaps, have

been better for him had his disposition led him to that line of life.

Such, however, had not been the case. He had already abandoned the

flute on which he had learned to sound three sad notes before he left

Guestwick, and, after the fifth or sixth Sunday, he had relinquished

his solitary walks along the towing-path of the Regent's Park

Canal. To think of one's absent love is very sweet; but it becomes

monotonous after a mile or two of a towing-path, and the mind

will turn away to Aunt Sally, the Cremorne Gardens, and financial

questions. I doubt whether any girl would be satisfied with her

lover's mind if she knew the whole of it.

"I say, Caudle, I wonder whether a fellow could get into a club?"

This proposition was made, on one of those Sunday walks, by John

Eames to the friend of his bosom, a brother clerk, whose legitimate

name was Cradell, and who was therefore called Caudle by his friends.

"Get into a club? Fisher in our room belongs to a club."

"That's only a chess-club. I mean a regular club."

"One of the swell ones at the West End?" said Cradell, almost lost in

admiration at the ambition of his friend.

"I shouldn't want it to be particularly swell. If a man isn't a

swell, I don't see what he gets by going among those who are. But

it is so uncommon slow at Mother Roper's." Now Mrs. Roper was a

respectable lady, who kept a boarding-house in Burton Crescent,

and to whom Mrs. Eames had been strongly recommended when she was

desirous of finding a specially safe domicile for her son. For the

first year of his life in London John Eames had lived alone in

lodgings; but that had resulted in discomfort, solitude, and, alas!

“Such young men are often awkward, ungainly, and not yet formed in their gait; they straggle with their limbs, and are shy; words do not come to them with ease, when words are required, among any but their accustomed associates. Social meetings are periods of penance to them, and any appearance in public will unnerve them. They go much about alone, and blush when women speak to them. In truth, they are not as yet men, whatever the number may be of their years; and, as they are no longer boys, the world has found for them the ungraceful name of hobbledehoy.”

"So I should like to see it. And so would mamma too, I'm sure; though

I never heard her say a word about him. In my mind he's the finest

fellow I ever saw. What's Mr. Apollo Crosbie to him? And now, as it

makes you unhappy, I'll never say another word about him."

As Bell wished her sister good-night with perhaps more than her usual

affection, it was evident that Lily's words and eager tone had in

some way pleased her, in spite of their opposition to the request

which she had made. And Lily was aware that it was so.

CHAPTER IV.

MRS. ROPER'S BOARDING-HOUSE.

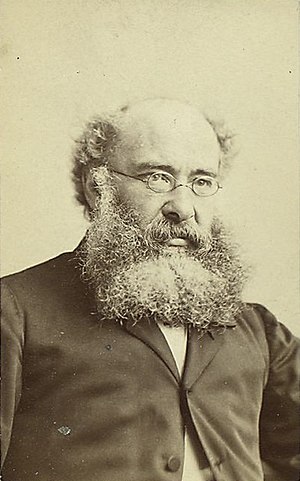

[ILLUSTRATION: (untitled)]

I have said that John Eames had been petted by none but his mother,

but I would not have it supposed, on this account, that John Eames

had no friends. There is a class of young men who never get petted,

though they may not be the less esteemed, or perhaps loved. They do

not come forth to the world as Apollos, nor shine at all, keeping

what light they may have for inward purposes. Such young men are

often awkward, ungainly, and not yet formed in their gait; they

straggle with their limbs, and are shy; words do not come to them

with ease, when words are required, among any but their accustomed

associates. Social meetings are periods of penance to them, and any

appearance in public will unnerve them. They go much about alone,

and blush when women speak to them. In truth, they are not as yet

men, whatever the number may be of their years; and, as they are no

longer boys, the world has found for them the ungraceful name of

hobbledehoy.

Such observations, however, as I have been enabled to make on this

matter have led me to believe that the hobbledehoy is by no means

the least valuable species of the human race. When I compare the

hobbledehoy of one or two and twenty to some finished Apollo of

the same age, I regard the former as unripe fruit, and the latter

as fruit that is ripe. Then comes the question as to the two fruits.

Which is the better fruit, that which ripens early--which is,

perhaps, favoured with some little forcing apparatus, or which, at

least, is backed by the warmth of a southern wall; or that fruit of

slower growth, as to which nature works without assistance, on which

the sun operates in its own time,--or perhaps never operates if some

ungenial shade has been allowed to interpose itself? The world, no

doubt, is in favour of the forcing apparatus or of the southern wall.

The fruit comes certainly, and at an assured period. It is spotless,

speckless, and of a certain quality by no means despicable.

“No man thinks there is much ado about nothing when the ado is about himself.”

She felt,

moreover, an expressible tenderness for his sorrow. When he declared

how cruel was his punishment, she could willingly have given him the

sympathy of her tears. For were not their cases in many points the

same?

She was determined to see him again before she went, and to tell him

that she acquitted him;--that she knew the greater fault was not with

him. This in itself would not comfort him; but she would endeavour so

to put it that he might draw comfort from it.

"I must see you for a moment alone, before I go," she said to him

that evening in the drawing-room. "I go very early on Thursday

morning. When can I speak to you? You are never up early, I know."

"But I will be to-morrow. Will you be afraid to come out with me

before breakfast?"

"Oh no! she would not be at all afraid," she said: and so the

appointment was made.

"I know you'll think me very foolish for giving this trouble," she

began, in rather a confused way, "and making so much about nothing."

"No man thinks there is much ado about nothing when the ado is about

himself," said Bertram, laughing.

"Well, but I know it is foolish. But I was unjust to you yesterday,

and I could not leave you without confessing it."

"How unjust, Adela?"

"I said you had cast Caroline off."

"Ah, no! I certainly did not do that."

"She wrote to me, and told me everything. She wrote very truly, I

know; and she did not say a word--not a word against you."

"Did she not? Well--no--I know she would not. And remember this,

Adela: I do not say a word against her. Do tell her, not from me, you

know, but of your own observation, that I do not say one word against

her. I only say she did not love me."

"Ah! Mr. Bertram."

"That is all; and that is true. Adela, I have not much to give; but I

would give it all--all--everything to have her back--to have her back

as I used to think her. But if I could have her now--as I know her

now--by raising this hand, I would not take her. But this imputes no

blame to her. She tried to love me, but she could not."

"Ah! she did love you.

“Its dogged as does it. It aint thinking about it.”

How is one of us to help hisself

against having on 'em? But there ain't no call for the loikes of you

to have the rheumatics."

"My friend," said Crawley, who was now standing on the road,--and

as he spoke he put out his arm and took the brickmaker by the hand,

"there is a worse complaint than rheumatism,--there is, indeed."

"There's what they calls the collerer," said Giles Hoggett, looking

up into Mr. Crawley's face. "That ain't a got a hold of yer?"

"Ay, and worse than the cholera. A man is killed all over when he is

struck in his pride;--and yet he lives."

"Maybe that's bad enough too," said Giles, with his hand still held

by the other.

"It is bad enough," said Mr. Crawley, striking his breast with his

left hand. "It is bad enough."

"Tell 'ee what, Master Crawley;--and yer reverence mustn't think as

I means to be preaching; there ain't nowt a man can't bear if he'll

only be dogged. You go whome, Master Crawley, and think o' that,

and maybe it'll do ye a good yet. It's dogged as does it. It ain't

thinking about it." Then Giles Hoggett withdrew his hand from the

clergyman's, and walked away towards his home at Hoggle End. Mr.

Crawley also turned homewards, and as he made his way through the

lanes, he repeated to himself Giles Hoggett's words. "It's dogged as

does it. It's not thinking about it."

[Illustration: "It's dogged as does it."]

He did not say a word to his wife on that afternoon about Dr.

Tempest; and she was so much taken up with his outward condition

when he returned, as almost to have forgotten the letter. He allowed

himself, but barely allowed himself, to be made dry, and then for

the remainder of the day applied himself to learn the lesson which

Hoggett had endeavoured to teach him. But the learning of it was not

easy, and hardly became more easy when he had worked the problem out

in his own mind, and discovered that the brickmaker's doggedness

simply meant self-abnegation;--that a man should force himself to

endure anything that might be sent upon him, not only without outward

grumbling, but also without grumbling inwardly.

“There is no happiness in love, except at the end of an English novel.”

But with me love will never act in that

way unless it is returned;' and he threw upon the signora a look of

tenderness which was intended to make up for all the deficiencies

of his speech.

'Take my advice,' said she. 'Never mind love. After all, what is

it? The dream of a few weeks. That is all its joy. The

disappointment of a life is its Nemesis. Who was ever successful in

true love? Success in love argues that the love is false. True love

is always despondent or tragical. Juliet loved. Haidee loved. Dido

loved, and what came of it? Troilus loved and ceased to be a man.'

'Troilus loved and he was fooled,' said the more manly chaplain. 'A

man may love and yet not be a Troilus. All women are not Cressids.'

'No; all women are not Cressids. The falsehood is not always on the

woman's side. Imogen was true, but now was she rewarded? Her lord

believed her to be the paramour of the first he who came near her

in his absence. Desdemona was true and was smothered. Ophelia was

true and went mad. There is no happiness in love, except at the end

of an English novel. But in wealth, money, houses, lands, goods and

chattels, in the good things of this world, yes, in them there is

something tangible, something that can be retained and enjoyed.'

'Oh, no,' said Mr Slope, feeling himself bound to enter some

protest against so very unorthodox a doctrine, 'this world's wealth

will make no one happy.'

'And what will make you happy--you--you?' said she, raising herself

up, and speaking to him with energy across the table. 'From what

source do you look for happiness? Do not say that you look for

none? I shall not believe you. It is a search in which every human

being spends an existence.'

'And the search is always in vain,' said Mr Slope. 'We look for

happiness on earth, while we ought to be content to hope for it in

heaven.'

'Pshaw! you preach a doctrine which you know you don't believe. It

is the way with you all. If you know that there is no earthly

happiness, why do you long to be a bishop or a dean? Why do you

want lands and income?

“There is no way of writing well and also of writing easily.”

How often does the

novelist feel, ay, and the historian also and the biographer, that

he has conceived within his mind and accurately depicted on the

tablet of his brain the full character and personage of a man, and

that nevertheless, when he flies to pen and ink to perpetuate the

portrait, his words forsake, elude, disappoint, and play the deuce

with him, till at the end of a dozen pages the man described has no

more resemblance to the man conceived than the sign board at the

corner of the street has to the Duke of Cambridge?

And yet such mechanical descriptive skill would hardly give more

satisfaction to the reader than the skill of the photographer does

to the anxious mother desirous to possess an absolute duplicate of

her beloved child. The likeness is indeed true; but it is a dull,

dead, unfeeling, inauspicious likeness. The face is indeed there,

and those looking at it will know at once whose image it is; but

the owner of the face will not be proud of the resemblance.

There is no royal road to learning; no short cut to the acquirement

of any art. Let photographers and daguerreotypers do what they

will, and improve as they may with further skill on that which

skill has already done, they will never achieve a portrait of the

human face as we may under the burdens which we so often feel too

heavy for our shoulders; we must either bear them up like men, or

own ourselves too weak for the work we have undertaken. There is no

way of writing well and also of writing easily.

Labor omnia vincit improbus. Such should be the chosen motto of

every labourer, and it may be that labour, if adequately enduring,

may suffice at last to produce even some not untrue resemblance of

the Rev. Francis Arabin.

Of his doings in the world, and of the sort of fame which he has

achieved, enough has already been said. It has also been said that

he is forty years of age, and still unmarried. He was the younger

son of a country gentleman of small fortune in the north of

England. At an early age he went to Winchester, and was intended by

his father for New College; but though studious as a boy, he was

not studious within the prescribed limits; and at the age of

eighteen he left school with a character for talent, but without a

scholarship. All that he had obtained, over and above the advantage

of his character, was a gold medal for English verse, and hence was

derived a strong presumption on the part of his friends that he was

destined to add another name to the imperishable list of English

poets.

“The end of a novel, like the end of a childrens dinner-party, must be made up of sweetmeats and sugar-plums.”

What could Mr Quiverful be to them,

or they to Mr Quiverful? Had Mr Harding indeed come back to them,

some last flicker of joyous light might have shone forth on their

aged cheeks; but it was in vain to bid them rejoice because Mr

Quiverful was about to move his fourteen children from Puddingdale

into the hospital house. In reality they did no doubt receive

advantage, spiritual as well as corporal; but this they could

neither anticipate nor acknowledge.

It was a dull affair enough, this introduction of Mr Quiverful; but

still it had its effect. The good which Mr Harding intended did not

fall to the ground. All the Barchester world, including the five

old bedesmen, treated Mr Quiverful with the more respect, because

Mr Harding had thus walked in arm in arm with him, on his first

entrance to his duties.

And here in their new abode we will leave Mr and Mrs Quiverful and

their fourteen children. May they enjoy the good things which

Providence has at length given to them!

CHAPTER LIII

CONCLUSION

The end of a novel, like the end of a children's dinner-party, must

be made up of sweetmeats and sugar-plums. There is now nothing else

to be told but the gala doings of Mr Arabin's marriage, nothing

more to be described than the wedding dresses, no further dialogue

to be recorded than that which took place between the archdeacon

who married them, and Mr Arabin and Eleanor who were married. 'Wilt

thou have this woman to thy wedded wife?' and 'Wilt thou have this

man to thy wedded husband, to live together according to God's

ordinance?' Mr Arabin and Eleanor each answered, 'I will'. We have

no doubt that they will keep their promises; the more especially as

the Signora Neroni had left Barchester before the ceremony was

performed.

Mrs Bold had been somewhat more than two years a widow before she

was married to her second husband, and little Johnnie was then able

with due assistance to walk on his own legs into the drawing-room

to receive the salutations of the assembled guests. Mr Harding gave

away the bride, the archdeacon performed the service, and the two

Miss Grantlys, who were joined in their labours by other young

ladies of the neighbourhood, performed the duties of bridesmaids

with equal diligence and grace.

“She well knew the great architectural secret of decorating her constructions, and never condescended to construct a decoration.”

Whatever conviction the

father may have had, the children were at any rate but indifferent

members of the church from which he drew his income.

Such was Dr Stanhope. The features of Mrs Stanhope's character were

even less plainly marked than those of her lord. The far niente of

her Italian life had entered into her very soul, and brought her to

regard a state of inactivity as the only earthly good. In manner

and appearance she was exceedingly prepossessing. She had been a

beauty, and even now, at fifty-five, she was a handsome woman. Her

dress was always perfect: she never dressed but once in the day,

and never appeared till between three and four; but when she did

appear, she appeared at her best. Whether the toil rested partly

with her, or wholly with her handmaid, it is not for such a one as

the author to imagine. The structure of her attire was always

elaborate, and yet never over laboured. She was rich in apparel,

but not bedizened with finery; her ornaments were costly, rare, and

such as could not fail to attract notice, but they did not look as

though worn with that purpose. She well knew the great

architectural secret of decorating her constructions, and never

condescended to construct a decoration. But when we have said that

Mrs Stanhope knew how to dress, and used her knowledge daily, we

have said all. Other purpose in life she had none. It was

something, indeed, that she did not interfere with the purposes of

others. In early life she had undergone great trials with reference

to the doctor's dinners; but for the last ten or twelve years her

eldest daughter Charlotte had taken that labour off her hands, and

she had had little to trouble her;--little, that is, till the edict

for this terrible English journey had gone forth; since, then,

indeed, her life had been laborious enough. For such a one, the

toil of being carried from the shores of Como to the city of

Barchester is more than labour enough, let the cares of the

carriers be ever so vigilant. Mrs Stanhope had been obliged to have

every one of her dresses taken in from the effects of the journey.

Charlotte Stanhope was at this time about thirty-five years old;

and, whatever may have been her faults, she had none of those which

belong particularly to old young ladies.

“The habit of reading is the only enjoyment in which there is no alloy; it lasts when all other pleasures fade.”

“The satirist who writes nothing but satire should write but little -- or it will seem that his satire springs rather from his own caustic nature than from the sins of the world in which he lives.”

“Never think that youre not good enough. A man should never think that. People will take you very much at your own reckoning.”

“Book love... is your pass to the greatest, the purest, and the most perfect pleasure that God has prepared for His creatures.”

“Life is so unlike theory.”

There is no happiness in love, except at the end of an English novel.

Romance is very pretty in novels, but the romance of a life is always a melancholy matter. They are most happy who have no story to tell.

I sometimes think you despise poetry, said Phineas. When it is false I do. The difficulty is to know when it is false and when it is true.

A small daily task, if it be really daily, will beat the labours of a spasmodic Hercules.

I have from the first felt sure that the writer, when he sits down to commence his novel, should do so, not because he has to tell a story, but because he has a story to tell. The novelists first novel will generally have sprung from the right cause.