“Power is not alluring to pure minds”

They obtained, at its commencement, all the amendments to

it they desired. These reconciled them to it perfectly, and if they have

any ulterior view, it is only, perhaps, to popularize it further,

by shortening the Senatorial term, and devising a process for the

responsibility of judges, more practicable than that of impeachment.

They esteem the people of England and France equally, and equally detest

the governing powers of both.

This I verily believe, after an intimacy of forty years with the public

councils and characters, is a true statement of the grounds on which

they are at present divided, and that it is not merely an ambition for

power. An honest man can feel no pleasure in the exercise of power over

his fellow-citizens. And considering as the only offices of power those

conferred by the people directly, that is to say, the executive and

legislative functions of the General and State governments, the common

refusal of these, and multiplied resignations, are proofs sufficient

that power is not alluring to pure minds, and is not, with them, the

primary principle of contest. This is my belief of it; it is that

on which I have acted; and had it been a mere contest who should

be permitted to administer the government according to its genuine

republican principles, there has never been a moment of my life, in

which I should not have relinquished for it the enjoyments of my family,

my farm, my friends, and books.

You expected to discover the difference of our party principles in

General Washingtons Valedictory, and my Inaugural Address. Not at all.

General Washington did not harbor one principle of federalism. He was

neither an Angloman, a monarchist, nor a separatist. He sincerely wished

the people to have as much self-government as they were competent to

exercise themselves. The only point in which he and I ever differed

in opinion, was, that I had more confidence than he had in the natural

integrity and discretion of the people, and in the safety and extent to

which they might trust themselves with a control over their government.

“I can not live with out books.”

the persons of our citizens shall be safe in freely traversing the

ocean, that the transportation of our own produce, in our own vessels,

to the markets of our choice, and the return to us of the articles we

want for our own use, shall be unmolested, I hold to be fundamental, and

that the gauntlet must be for ever hurled at him who questions it. But

whether we shall engage in every war of Europe, to protect the mere

agency of our merchants and shipowners in carrying on the commerce of

other nations, even were those merchants and ship-owners to take the

side of their country in the contest, instead of that of the enemy, is a

question of deep and serious consideration, with which, however, you and

I shall have nothing to do; so we will leave it to those whom it will

concern.

I thank you for making known to me Mr. Ticknor and Mr. Gray. They are

fine young men, indeed, and if Massachusetts can raise a few more such,

it is probable she would be better counselled as to social rights and

social duties. Mr. Ticknor is, particularly, the best bibliograph I

have met with, and very kindly and opportunely offered me the means of

reprocuring some part of the literary treasures which I have ceded

to Congress, to replace the devastations of British Vandalism at

Washington. I cannot live without books. But fewer will suffice, where

amusement, and not use, is the only future object. I am about sending

him a catalogue, to which less than his critical knowledge of books

would hardly be adequate.

Present my high respects to Mrs. Adams, and accept yourself the

assurances of my affectionate attachment.

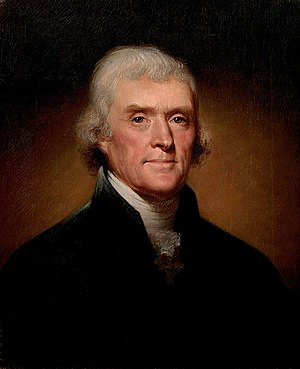

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER CXXVII.--TO MR. LEIPER, June 12, 1815

TO MR. LEIPER.

Monticello, June 12, 1815.

Dear Sir,

A journey soon after the receipt of your favor of April the 17th and

an absence from home of some continuance, have prevented my earlier

acknowledgment of it. In that came safely my letter of January the 2nd,

1814. In our principles of government we differ not at all; nor in the

general object and tenor of political measures. We concur in considering

the government of England as totally without morality, insolent beyond

bearing, inflated with vanity and ambition, aiming at the exclusive

dominion of the sea, lost in corruption, of deep-rooted hatred towards

us, hostile to liberty wherever it endeavors to show its head, and

the eternal disturber of the peace of the world.

“I am of a sect by myself, as far as I know”

The times in which I have lived, and the scenes in which I have been

engaged, have required me to keep the mind too much in action to have

leisure to study minutely its laws of action. I am therefore little

qualified to give an opinion on the comparative worth of books on that

subject, and little disposed to do it on any book. Yours has brought

the science within a small compass, and that is the merit of the first

order; and especially with one to whom the drudgery of letter writing

often denies the leisure of reading a single page in a week. On looking

over the summary of the contents of your book, it does not seem likely

to bring into collision any of those sectarian differences which you

suppose may exist between us. In that branch of religion which regards

the moralities of life, and the duties of a social being, which teaches

us to love our neighbors as ourselves, and to do good to all men, I am

sure that you and I do not differ. We probably differ in the dogmas of

theology, the foundation of all sectarianism, and on which no two sects

dream alike; for if they did they would then be of the same. You say

you are a Calvinist. I am not. I am of a sect by myself, as far as I

know. I am not a Jew, and therefore do not adopt their theology, which

supposes the God of infinite justice to punish the sins of the fathers

upon their children, unto the third and fourth generation; and the

benevolent and sublime reformer of that religion has told us only that

God is good and perfect, but has not defined him. I am, therefore, of his

theology, believing that we have neither words nor ideas adequate to that

definition. And if we could all, after this example, leave the subject as

undefinable, we should all be of one sect, doers of good, and eschewers

of evil. No doctrines of his lead to schism. It is the speculations of

crazy theologists which have made a Babel of a religion the most moral

and sublime ever preached to man, and calculated to heal, and not to

create differences. These religious animosities I impute to those who

call themselves his ministers, and who engraft their casuistries on the

stock of his simple precepts. I am sometimes more angry with them than

is authorized by the blessed charities which he preaches.

I had rather be shut up in a very modest cottage with my books, my family and a few old friends, dining on simple bacon, and letting the world roll on as it liked, than to occupy the most splendid post, which any human power can give.

It is true, that the distrust existing between

the two courts of Versailles and London, is so great, that they can

scarcely do business together. However, the difficulty and doubt

of obtaining money make both afraid to enter into war. The little

preparations for war, which we see, are the effect of distrust, rather

than of a design to commence hostilities. And in such a state of mind,

you know, small things may produce a rupture: so that though peace is

rather probable, war is very possible.

Your letter has kindled all the fond recollections of ancient times;

recollections much dearer to me than any thing I have known since. There

are minds which can be pleased by honors and preferments; but I see

nothing in them but envy and enmity. It is only necessary to possess

them, to know how little they contribute to happiness, or rather how

hostile they are to it. No attachments soothe the mind so much as those

contracted in early life; nor do I recollect any societies which have

given me more pleasure, than those of which you have partaken with me.

1 had rather be shut up in a very modest cottage, with my books, my

family, and a few old friends, dining on simple bacon, and letting the

world roll on as it liked, than to occupy the most splendid post, which

any human power can give. I shall be glad to hear from you often. Give

me the small news as well as the great. Tell Dr. Currie, that I believe

I am indebted to him a letter, but that like the mass of our countrymen,

I am not, at this moment, able to pay all my debts; the post being to

depart in an hour, and the last stroke of a pen I am able to send by it,

being that which assures you of the sentiments of esteem and attachment,

with which I am, Dear Sir, your affectionate friend and servant,

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER CXXVII.--TO M. WARVILLE, February 12, 1888

TO M. WARVILLE.

Paris, February 12, 1888.

Sir,

I am very sensible of the honor you propose to me, of becoming a member

of the society for the abolition of the slave-trade. You know that

nobody wishes more ardently, to see an abolition, not only of the trade,

but of the condition of slavery: and certainly nobody will be more

willing to encounter every sacrifice for that object. But the influence

and information of the friends to this proposition in France will be

far above the need of my association.

The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.

30, if a person brought up in the Christian religion

denies the being of a God, or the Trinity, or asserts there are

more gods than one, or denies the Christian religion to be true,

or the scriptures to be of divine authority, he is punishable on

the first offence by incapacity to hold any office or employment

ecclesiastical, civil, or military; on the second by disability to

sue, to take any gift or legacy, to be guardian, executor, or administrator,

and by three years' imprisonment without bail. A

father's right to the custody of his own children being founded

in law on his right of guardianship, this being taken away, they

may of course be severed from him, and put by the authority of

a court into more orthodox hands. This is a summary view of

that religious slavery under which a people have been willing

to remain, who have lavished their lives and fortunes for the establishment

of their civil freedom. [63]The error seems not sufficiently

eradicated, that the operations of the mind, as well as

the acts of the body, are subject to the coercion of the laws. But

our rulers can have no authority over such natural rights, only

as we have submitted to them. The rights of conscience we

never submitted, we could not submit. We are answerable for

them to our God. The legitimate powers of government extend

to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no

injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no God.

It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg. If it be said, his

testimony in a court of justice cannot be relied on, reject it then,

and be the stigma on him. Constraint may make him worse by

making him a hypocrite, but it will never make him a truer man.

It may fix him obstinately in his errors, but will not cure them.

Reason and free inquiry are the only effectual agents against

error. Give a loose to them, they will support the true religion

by bringing every false one to their tribunal, to the test of their

investigation. They are the natural enemies of error, and of

error only. Had not the Roman government permitted free inquiry,

Christianity could never have been introduced. Had not

free inquiry been indulged at the era of the reformation, the corruptions

of Christianity could not have been purged away. If it

be restrained now, the present corruptions will be protected, and

new ones encouraged. Was the government to prescribe to us

our medicine and diet, our bodies would be in such keeping as

our souls are now.

All should be laid open to you without reserve, for there is not a truth existing which I fear, or would wish unknown to the whole world.

It happened that during

those eight days of incessant labor, for the benefit of my own memory,

I carefully noted every circumstance worth it. These memorandums were

often written on horseback, and on scraps of paper taken out of my

pocket at the moment, fortunately preserved to this day, and now lying

before me. I wish you could see them. But my papers of that period are

stitched together in large masses, and so tattered and tender as not to

admit removal further than from their shelves to a reading table. They

bear an internal evidence of fidelity which must carry conviction to

every one who sees them. We have nothing in our neighborhood which could

compensate the trouble of a visit to it, unless perhaps our University,

which I believe you have not seen, and I can assure you is worth seeing.

Should you think so, I would ask as much of your time at Monticello

as would enable you to examine these papers at your ease. Many others

too are interspersed among them, which have relation to your object,

many letters from Generals Gates, Greene, Stephens and others engaged

in the Southern war, and in the North also. All should be laid open to

you without reserve, for there is not a truth existing which I fear, or

would wish unknown to the whole world. During the invasions of Arnold,

Phillips and Cornwallis, until my time of office had expired, I made it

a point, once a week, by letters to the President of Congress, and to

General Washington, to give them an exact narrative of the transactions

of the week. These letters should still be in the office of state in

Washington, and in the presses at Mount Vernon. Or, if the former were

destroyed by the conflagrations of the British, the latter are surely

safe, and may be appealed to in corroboration of what I have now written.

There is another transaction, very erroneously stated in the same work,

which although not concerning myself, is within my own knowledge, and I

think it a duty to communicate it to you. I am sorry that not being in

possession of a copy of the memoirs, I am not able to quote the page,

and still less the facts themselves, verbatim from the text. But of the

substance, as recollected, I am certain. It is said there that, about

the time of Tarleton's expedition up the north branch of James river

to Charlottesville and Monticello, Simcoe was detached up the southern

branch, and penetrated as far as New London, in Bedford, where he

destroyed a depôt of arms, &c.

I was bold in the pursuit of knowledge, never fearing to follow truth and reason to whatever results they led.

I

consider the continuance of republican government as absolutely hanging

on these two hooks. Of the first, you will, I am sure, be an advocate,

as having already reflected on it, and of the last, when you shall have

reflected. Ever affectionately yours.

TO THOMAS COOPER, ESQ.

MONTICELLO, February 10, 1814.

DEAR SIR,--In my letter of January 16, I promised you a sample from my

common-place book, of the pious disposition of the English judges, to

connive at the frauds of the clergy, a disposition which has even rendered

them faithful allies in practice. When I was a student of the law, now

half a century ago, after getting through Coke Littleton, whose matter

cannot be abridged, I was in the habit of abridging and common-placing

what I read meriting it, and of sometimes mixing my own reflections on

the subject. I now enclose you the extract from these entries which

I promised. They were written at a time of life when I was bold in

the pursuit of knowledge, never fearing to follow truth and reason to

whatever results they led, and bearding every authority which stood in

their way. This must be the apology, if you find the conclusions bolder

than historical facts and principles will warrant. Accept with them the

assurances of my great esteem and respect.

_Common-place Book._

873. In Quare imp. in C. B. 34, H. 6, fo. 38, the def. Br. of Lincoln

pleads that the church of the pl. became void by the death of the

incumbent, that the pl. and J. S. each pretending a right, presented

two several clerks; that the church being thus rendered litigious, he

was not obliged, by the _Ecclesiastical law_ to admit either, until an

inquisition de jure patronatus, in the ecclesiastical court: that, by

the same law, this inquisition was to be at the suit of either claimant,

and was not _ex-officio_ to be instituted by the bishop, and at his

proper costs; that neither party had desired such an inquisition; that

six months passed whereon it belonged to him of right to present as

on a lapse, which he had done. The pl.

It is error alone which needs the support of government. Truth can stand by itself.

Was the government to prescribe to us

our medicine and diet, our bodies would be in such keeping as

our souls are now. Thus in France the emetic was once forbidden

as a medicine, and the potato as an article of food. Government

is just as infallible, too, when it fixes systems in physics.

Galileo was sent to the Inquisition for affirming that the earth

was a sphere; the government had declared it to be as flat as a

trencher, and Galileo was obliged to abjure his error. This

error, however, at length prevailed, the earth became a globe, and

Descartes declared it was whirled round its axis by a vortex.

The government in which he lived was wise enough to see that

this was no question of civil jurisdiction, or we should all have

been involved by authority in vortices. In fact, the vortices

have been exploded, and the Newtonian principle of gravitation

is now more firmly established, on the basis of reason, than it

would be were the government to step in, and to make it an

article of necessary faith. Reason and experiment have been

indulged, and error has fled before them. It is error alone which

needs the support of government. Truth can stand by itself.

Subject opinion to coercion: whom will you make your inquisitors?

Fallible men; men governed by bad passions, by private

as well as public reasons. And why subject it to coercion? To

produce uniformity. But is uniformity of opinion desirable?

No more than of face and stature. Introduce the bed of Procrustes

then, and as there is danger that the large men may beat

the small, make us all of a size, by lopping the former and

stretching the latter. Difference of opinion is advantageous in

religion. The several sects perform the office of a _censor morum_

over such other. Is uniformity attainable? Millions of innocent

men, women, and children, since the introduction of Christianity,

have been burnt, tortured, fined, imprisoned; yet we have not

advanced one inch towards uniformity. What has been the effect

of coercion? To make one half the world fools, and the

other half hypocrites. To support roguery and error all over

the earth. Let us reflect that it is inhabited by a thousand millions

of people.

And for the support of this declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.

They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity.

We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our

Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in

War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the United States of America, in

General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the

world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by the

Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and

declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free

and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to

the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and

the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and

that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War,

conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all

other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And

for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the

Protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our

Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

About this etext

The Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence was the first Etext

released by Project Gutenberg, early in 1971. The title was stored in

an emailed instruction set which required a tape or diskpack be hand

mounted for retrieval. The diskpack was the size of a large cake in a

cake carrier, cost $1500, and contained 5 megabytes, of which this file

took 1-2%. Two tape backups were kept plus one on paper tape. The

10,000 files we hope to have online by the end of 2001 should take

about 1-2% of a comparably priced drive in 2001.

This file was never copyrighted, Sharewared, etc., and is thus for all

to use and copy in any manner they choose. Please feel free to make

your own edition using this as a base.

In my research for creating this transcription of our first Etext, I

have come across enough discrepancies [even within that official

documentation provided by the United States] to conclude that even

"facsimiles" of the Declaration of Indendence will NOT going to be all

the same as the original, nor of other "facsimiles.

“I may grow rich by an art I am compelled to follow; I may recover health by medicines I am compelled to take against my own judgment; but I cannot be saved by a worship I disbelieve and abhor”

“The Christian God is a being of terrific character - cruel, vindictive, capricious, and unjust”

“We discover (in the gospels) a groundwork of vulgar ignorance, of things impossible, of superstition, fanaticism and fabrication”

“They (preachers) dread the advance of science as witches do the approach of daylight and scowl on the fatal harbinger announcing the subversions of the duperies on which they live”

“Never tell the truth to those unworthy of it....”

“A half-truth is a whole lie”

“The tree of liberty must be watered periodically with the blood of tyrants and patriots alike. It is its natural manure.”

“No free man shall ever be debarred the use of arms.”

“Whatever enables us to go to war, secures our peace”

“Information is the currency of democracy.”

“It is incumbent on every generation to pay its own debts as it goes. A principle which if acted on would save one-half the wars of the world.”