“There are few hours in life more agreeable than the hour dedicated to the ceremony known as afternoon tea”

So early was to begin my tendency to _overtreat_,

rather than undertreat (when there was choice or danger) my subject.

(Many members of my craft, I gather, are far from agreeing with me, but

I have always held overtreating the minor disservice.) "Treating" that

of "The Portrait" amounted to never forgetting, by any lapse, that the

thing was under a special obligation to be amusing. There was the danger

of the noted "thinness"--which was to be averted, tooth and nail,

by cultivation of the lively. That is at least how I see it to-day.

Henrietta must have been at that time a part of my wonderful notion of

the lively. And then there was another matter. I had, within the few

preceding years, come to live in London, and the "international" light

lay, in those days, to my sense, thick and rich upon the scene. It was

the light in which so much of the picture hung. But that _is_ another

matter. There is really too much to say.

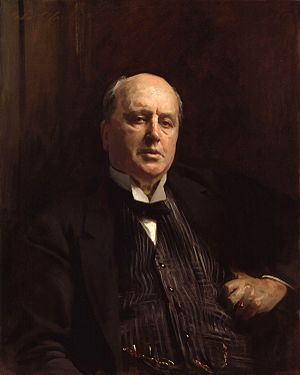

HENRY JAMES

THE PORTRAIT OF A LADY

CHAPTER I

Under certain circumstances there are few hours in life more agreeable

than the hour dedicated to the ceremony known as afternoon tea. There

are circumstances in which, whether you partake of the tea or not--some

people of course never do,--the situation is in itself delightful. Those

that I have in mind in beginning to unfold this simple history offered

an admirable setting to an innocent pastime. The implements of

the little feast had been disposed upon the lawn of an old English

country-house, in what I should call the perfect middle of a splendid

summer afternoon. Part of the afternoon had waned, but much of it was

left, and what was left was of the finest and rarest quality. Real dusk

would not arrive for many hours; but the flood of summer light had begun

to ebb, the air had grown mellow, the shadows were long upon the smooth,

dense turf. They lengthened slowly, however, and the scene expressed

that sense of leisure still to come which is perhaps the chief source

of one's enjoyment of such a scene at such an hour. From five o'clock to

eight is on certain occasions a little eternity; but on such an occasion

as this the interval could be only an eternity of pleasure.

“Tea was such a comfort.”

When I suggested that she was perhaps a woman of title with

whom he was conscientiously flirting my informant replied: “She is

indeed, but do you know what her title is?” He pronounced it—it was

familiar and descriptive—but I won’t reproduce it here. I don’t know

whether Leolin mentioned it to his mother: she would have needed all the

purity of the artist to forgive him. I hated so to come across him that

in the very last years I went rarely to see her, though I knew that she

had come pretty well to the end of her rope. I didn’t want her to tell

me that she had fairly to give her books away—I didn’t want to see her

cry. She kept it up amazingly, and every few months, at my club, I saw

three new volumes, in green, in crimson, in blue, on the book-table that

groaned with light literature. Once I met her at the Academy soirée,

where you meet people you thought were dead, and she vouchsafed the

information, as if she owed it to me in candour, that Leolin had been

obliged to recognise insuperable difficulties in the question of _form_,

he was so fastidious; so that she had now arrived at a definite

understanding with him (it was such a comfort) that _she_ would do the

form if he would bring home the substance. That was now his position—he

foraged for her in the great world at a salary. “He’s my ‘devil,’ don’t

you see? as if I were a great lawyer: he gets up the case and I argue

it.” She mentioned further that in addition to his salary he was paid by

the piece: he got so much for a striking character, so much for a pretty

name, so much for a plot, so much for an incident, and had so much

promised him if he would invent a new crime.

“He _has_ invented one,” I said, “and he’s paid every day of his life.”

“What is it?” she asked, looking hard at the picture of the year; “Baby’s

Tub,” near which we happened to be standing.

I hesitated a moment. “I myself will write a little story about it, and

then you’ll see.”

But she never saw; she had never seen anything, and she passed away with

her fine blindness unimpaired. Her son published every scrap of

scribbled paper that could be extracted from her table-drawers, and his

sister quarrelled with him mortally about the proceeds, which showed that

she only wanted a pretext, for they cannot have been great.

“No sovereign, no court, no personal loyalty, no aristocracy, no church, no clergy, no army, no diplomatic service, no country gentlemen, no palaces, no castles, nor manors, nor old country-houses, nor parsonages, nor thatched cottages nor ivied ruins; no cathedrals, nor abbeys, nor little Norman churches; no great Universities nor public schools / no Oxford, nor Eton, nor Harrow; no literature, no novels, no museums, no pictures, no political society, no sporting class / no Epsom nor Ascot! Some such list as that might be drawn up of the absent things in American life.”

It takes so many things, as Hawthorne must

have felt later in life, when he made the acquaintance of the denser,

richer, warmer-European spectacle--it takes such an accumulation of

history and custom, such a complexity of manners and types, to form a

fund of suggestion for a novelist. If Hawthorne had been a young

Englishman, or a young Frenchman of the same degree of genius, the

same cast of mind, the same habits, his consciousness of the world

around him would have been a very different affair; however obscure,

however reserved, his own personal life, his sense of the life of his

fellow-mortals would have been almost infinitely more various. The

negative side of the spectacle on which Hawthorne looked out, in his

contemplative saunterings and reveries, might, indeed, with a little

ingenuity, be made almost ludicrous; one might enumerate the items of

high civilization, as it exists in other countries, which are absent

from the texture of American life, until it should become a wonder to

know what was left. No State, in the European sense of the word, and

indeed barely a specific national name. No sovereign, no court, no

personal loyalty, no aristocracy, no church, no clergy, no army, no

diplomatic service, no country gentlemen, no palaces, no castles, nor

manors, nor old country-houses, nor parsonages, nor thatched cottages

nor ivied ruins; no cathedrals, nor abbeys, nor little Norman

churches; no great Universities nor public schools--no Oxford, nor

Eton, nor Harrow; no literature, no novels, no museums, no pictures,

no political society, no sporting class--no Epsom nor Ascot! Some such

list as that might be drawn up of the absent things in American

life--especially in the American life of forty years ago, the effect

of which, upon an English or a French imagination, would probably as a

general thing be appalling. The natural remark, in the almost lurid

light of such an indictment, would be that if these things are left

out, everything is left out. The American knows that a good deal

remains; what it is that remains--that is his secret, his joke, as one

may say. It would be cruel, in this terrible denudation, to deny him

the consolation of his national gift, that "American humour" of which

of late years we have heard so much.

But in helping us to measure what remains, our author's Diaries, as I

have already intimated, would give comfort rather to persons who might

have taken the alarm from the brief sketch I have just attempted of

what I have called the negative side of the American social situation,

than to those reminding themselves of its fine compensations.

Hawthorne's entries are to a great degree accounts of walks in the

country, drives in stage-coaches, people he met in taverns.

“I think I dont regret a single excess of my responsive youth-I only regret, in my chilled age, certain occasions and possibilities I didnt embrace.”

I

make out that you will then be in London again--I mean _by_ November,

though such a black gulf of time intervenes; and then of course I may

look to you to come down to me for a couple of days. It will be the

lowest kind of "jinks"--so halting is my pace; yet we shall somehow make

it serve. Don't say to me, by the way, à propos of jinks--the "high"

kind that you speak of having so wallowed in previous to leaving

town--that I ever challenge you as to _why_ you wallow, or splash or

plunge, or dizzily and sublimely soar (into the jinks element,) or

whatever you may call it: as if I ever remarked on anything but the

absolute inevitability of it for you at your age and with your natural

curiosities, as it were, and passions. It's good healthy exercise, when

it comes but in bouts and brief convulsions, and it's always a kind of

thing that it's good, and considerably final, to _have_ done. We must

know, as much as possible, in our beautiful art, yours and mine, what we

are talking about--and the only way to know is to have lived and loved

and cursed and floundered and enjoyed and suffered. I think I don't

regret a single "excess" of my responsive youth--I only regret, in my

chilled age, certain occasions and possibilities I didn't embrace. Bad

doctrine to impart to a young idiot or duffer, but in place for a young

friend (pressed to my heart) with a fund of nobler passion, the

preserving, the defying, the dedicating, and which always has the last

word; the young friend who can dip and shake off and go his straight way

again when it's time. But we'll talk of all this--it's absolutely late.

Who is D. H. Lawrence, who, you think, would interest me? Send him and

his book along--by which I simply mean Inoculate me, at your convenience

(don't address me the volume), so far as I can _be_ inoculated. I always

_try_ to let anything of the kind "take." Last year, you remember, a

couple of improbabilities (as to "taking") did worm a little into the

fortress. (Gilbert Cannan was one.) I have been reading over Tolstoi's

interminable _Peace and War_, and am struck with the fact that I now

protest as much as I admire. He doesn't _do_ to read over, and that

exactly is the answer to those who idiotically proclaim the impunity of

such formless shape, such flopping looseness and such a denial of

composition, selection and style.

“Live all you can; its a mistake not to. It doesnt so much matter what you do in particular, so long as you have your life. If you havent had that what have you had?”

And

when after this little Bilham, submissive and responsive, but with an

eye to the consolation nearest, easily threw off some “Better late than

never!” all he got in return for it was a sharp “Better early than

late!” This note indeed the next thing overflowed for Strether into a

quiet stream of demonstration that as soon as he had let himself go he

felt as the real relief. It had consciously gathered to a head, but the

reservoir had filled sooner than he knew, and his companion’s touch was

to make the waters spread. There were some things that had to come in

time if they were to come at all. If they didn’t come in time they were

lost for ever. It was the general sense of them that had overwhelmed

him with its long slow rush.

“It’s not too late for _you_, on any side, and you don’t strike me as

in danger of missing the train; besides which people can be in general

pretty well trusted, of course—with the clock of their freedom ticking

as loud as it seems to do here—to keep an eye on the fleeting hour. All

the same don’t forget that you’re young—blessedly young; be glad of it

on the contrary and live up to it. Live all you can; it’s a mistake not

to. It doesn’t so much matter what you do in particular, so long as you

have your life. If you haven’t had that what _have_ you had? This place

and these impressions—mild as you may find them to wind a man up so;

all my impressions of Chad and of people I’ve seen at _his_ place—well,

have had their abundant message for me, have just dropped _that_ into

my mind. I see it now. I haven’t done so enough before—and now I’m old;

too old at any rate for what I see. Oh I _do_ see, at least; and more

than you’d believe or I can express. It’s too late. And it’s as if the

train had fairly waited at the station for me without my having had the

gumption to know it was there. Now I hear its faint receding whistle

miles and miles down the line. What one loses one loses; make no

mistake about that. The affair—I mean the affair of life—couldn’t, no

doubt, have been different for me; for it’s at the best a tin mould,

either fluted and embossed, with ornamental excrescences, or else

smooth and dreadfully plain, into which, a helpless jelly, one’s

consciousness is poured—so that one ‘takes’ the form as the great cook

says, and is more or less compactly held by it: one lives in fine as

one can.

“Do not mind anything that anyone tells you about anyone else. Judge everyone and everything for yourself.”

He lives on his income, which I suspect of not being vulgarly

large. He's a poor but honest gentleman that's what he calls himself.

He married young and lost his wife, and I believe he has a daughter. He

also has a sister, who's married to some small Count or other, of these

parts; I remember meeting her of old. She's nicer than he, I should

think, but rather impossible. I remember there used to be some stories

about her. I don't think I recommend you to know her. But why don't you

ask Madame Merle about these people? She knows them all much better than

I."

"I ask you because I want your opinion as well as hers," said Isabel.

"A fig for my opinion! If you fall in love with Mr. Osmond what will you

care for that?"

"Not much, probably. But meanwhile it has a certain importance. The more

information one has about one's dangers the better."

"I don't agree to that--it may make them dangers. We know too much about

people in these days; we hear too much. Our ears, our minds, our mouths,

are stuffed with personalities. Don't mind anything any one tells you

about any one else. Judge everyone and everything for yourself."

"That's what I try to do," said Isabel "but when you do that people call

you conceited."

"You're not to mind them--that's precisely my argument; not to mind what

they say about yourself any more than what they say about your friend or

your enemy."

Isabel considered. "I think you're right; but there are some things I

can't help minding: for instance when my friend's attacked or when I

myself am praised."

"Of course you're always at liberty to judge the critic. Judge people as

critics, however," Ralph added, "and you'll condemn them all!"

"I shall see Mr. Osmond for myself," said Isabel. "I've promised to pay

him a visit."

"To pay him a visit?"

"To go and see his view, his pictures, his daughter--I don't know

exactly what. Madame Merle's to take me; she tells me a great many

ladies call on him."

"Ah, with Madame Merle you may go anywhere, _de confiance_," said Ralph.

"She knows none but the best people."

Isabel said no more about Mr. Osmond, but she presently remarked to her

cousin that she was not satisfied with his tone about Madame Merle.

It has made me better loving you... it has made me wiser, and easier, and brighter. I used to want a great many things before, and to be angry that I did not have them. Theoretically, I was satisfied. I flattered myself that I had limited my wants. But I was subject to irritation; I used to have morbid sterile hateful fits of hunger, of desire. Now I really am satisfied, because I can’t think of anything better. It’s just as when one has been trying to spell out a book in the twilight, and suddenly the lamp comes in. I had been putting out my eyes over the book of life, and finding nothing to reward me for my pains; but now that I can read it properly I see that it’s a delightful story.

I don't care what people of whom I ask nothing

think--I'm not even capable perhaps of wanting to know. I've never so

concerned myself, God forgive me, and why should I begin to-day, when I

have taken to myself a compensation for everything? I won't pretend

I'm sorry you're rich; I'm delighted. I delight in everything that's

yours--whether it be money or virtue. Money's a horrid thing to follow,

but a charming thing to meet. It seems to me, however, that I've

sufficiently proved the limits of my itch for it: I never in my life

tried to earn a penny, and I ought to be less subject to suspicion than

most of the people one sees grubbing and grabbing. I suppose it's their

business to suspect--that of your family; it's proper on the whole they

should. They'll like me better some day; so will you, for that matter.

Meanwhile my business is not to make myself bad blood, but simply to

be thankful for life and love." "It has made me better, loving you," he

said on another occasion; "it has made me wiser and easier and--I won't

pretend to deny--brighter and nicer and even stronger. I used to want

a great many things before and to be angry I didn't have them.

Theoretically I was satisfied, as I once told you. I flattered myself

I had limited my wants. But I was subject to irritation; I used to

have morbid, sterile, hateful fits of hunger, of desire. Now I'm really

satisfied, because I can't think of anything better. It's just as when

one has been trying to spell out a book in the twilight and suddenly the

lamp comes in. I had been putting out my eyes over the book of life and

finding nothing to reward me for my pains; but now that I can read it

properly I see it's a delightful story. My dear girl, I can't tell you

how life seems to stretch there before us--what a long summer afternoon

awaits us. It's the latter half of an Italian day--with a golden haze,

and the shadows just lengthening, and that divine delicacy in the light,

the air, the landscape, which I have loved all my life and which you

love to-day. Upon my honour, I don't see why we shouldn't get on. We've

got what we like--to say nothing of having each other. We've the faculty

of admiration and several capital convictions. We're not stupid, we're

not mean, we're not under bonds to any kind of ignorance or dreariness.

You're remarkably fresh, and I'm remarkably well-seasoned. We've my poor

child to amuse us; we'll try and make up some little life for her. It's

all soft and mellow--it has the Italian colouring."

They made a good many plans, but they left themselves also a good deal

of latitude; it was a matter of course, however, that they should live

for the present in Italy. It was in Italy that they had met, Italy had

been a party to their first impressions of each other, and Italy

should be a party to their happiness.

Live all you can: its a mistake not to. It doesnt matter what you do in particular, so long as you have had your life. If you havent had that, what have you had?

And

when after this little Bilham, submissive and responsive, but with an

eye to the consolation nearest, easily threw off some “Better late than

never!” all he got in return for it was a sharp “Better early than

late!” This note indeed the next thing overflowed for Strether into a

quiet stream of demonstration that as soon as he had let himself go he

felt as the real relief. It had consciously gathered to a head, but the

reservoir had filled sooner than he knew, and his companion’s touch was

to make the waters spread. There were some things that had to come in

time if they were to come at all. If they didn’t come in time they were

lost for ever. It was the general sense of them that had overwhelmed

him with its long slow rush.

“It’s not too late for _you_, on any side, and you don’t strike me as

in danger of missing the train; besides which people can be in general

pretty well trusted, of course—with the clock of their freedom ticking

as loud as it seems to do here—to keep an eye on the fleeting hour. All

the same don’t forget that you’re young—blessedly young; be glad of it

on the contrary and live up to it. Live all you can; it’s a mistake not

to. It doesn’t so much matter what you do in particular, so long as you

have your life. If you haven’t had that what _have_ you had? This place

and these impressions—mild as you may find them to wind a man up so;

all my impressions of Chad and of people I’ve seen at _his_ place—well,

have had their abundant message for me, have just dropped _that_ into

my mind. I see it now. I haven’t done so enough before—and now I’m old;

too old at any rate for what I see. Oh I _do_ see, at least; and more

than you’d believe or I can express. It’s too late. And it’s as if the

train had fairly waited at the station for me without my having had the

gumption to know it was there. Now I hear its faint receding whistle

miles and miles down the line. What one loses one loses; make no

mistake about that. The affair—I mean the affair of life—couldn’t, no

doubt, have been different for me; for it’s at the best a tin mould,

either fluted and embossed, with ornamental excrescences, or else

smooth and dreadfully plain, into which, a helpless jelly, one’s

consciousness is poured—so that one ‘takes’ the form as the great cook

says, and is more or less compactly held by it: one lives in fine as

one can.

True happiness, we are told, consists in getting out of ones self; but the point is not only to get out - you must stay out; and to stay out you must have some absorbing errand.

It is still

lotus-eating, only you sit down at table, and the lotuses are served up

on rococo china. It 's all very well, but I have a distinct prevision of

this--that if Roman life does n't do something substantial to make you

happier, it increases tenfold your liability to moral misery. It seems

to me a rash thing for a sensitive soul deliberately to cultivate its

sensibilities by rambling too often among the ruins of the Palatine, or

riding too often in the shadow of the aqueducts. In such recreations the

chords of feeling grow tense, and after-life, to spare your intellectual

nerves, must play upon them with a touch as dainty as the tread of

Mignon when she danced her egg-dance."

"I should have said, my dear Rowland," said Cecilia, with a laugh, "that

your nerves were tough, that your eggs were hard!"

"That being stupid, you mean, I might be happy? Upon my word I am not.

I am clever enough to want more than I 've got. I am tired of myself, my

own thoughts, my own affairs, my own eternal company. True happiness,

we are told, consists in getting out of one's self; but the point is not

only to get out--you must stay out; and to stay out you must have some

absorbing errand. Unfortunately, I 've got no errand, and nobody will

trust me with one. I want to care for something, or for some one. And I

want to care with a certain ardor; even, if you can believe it, with

a certain passion. I can't just now feel ardent and passionate about a

hospital or a dormitory. Do you know I sometimes think that I 'm a man

of genius, half finished? The genius has been left out, the faculty of

expression is wanting; but the need for expression remains, and I spend

my days groping for the latch of a closed door."

"What an immense number of words," said Cecilia after a pause, "to say

you want to fall in love! I 've no doubt you have as good a genius for

that as any one, if you would only trust it."

"Of course I 've thought of that, and I assure you I hold myself ready.

But, evidently, I 'm not inflammable. Is there in Northampton some

perfect epitome of the graces?"

"Of the graces?" said Cecilia, raising her eyebrows and suppressing too

distinct a consciousness of being herself a rosy embodiment of several.

She took refuge on the firm ground of fiction, through which indeed there curled the blue river of truth.

Wix's tone, which in spite of caricature remained

indescribable and inimitable, that Maisie, before her term with her

mother was over, drew this sense of a support, like a breast-high

banister in a place of "drops," that would never give way. If she knew

her instructress was poor and queer she also knew she was not nearly so

"qualified" as Miss Overmore, who could say lots of dates straight off

(letting you hold the book yourself), state the position of Malabar, play

six pieces without notes and, in a sketch, put in beautifully the trees

and houses and difficult parts. Maisie herself could play more pieces

than Mrs. Wix, who was moreover visibly ashamed of her houses and trees

and could only, with the help of a smutty forefinger, of doubtful

legitimacy in the field of art, do the smoke coming out of the chimneys.

They dealt, the governess and her pupil, in "subjects," but there were

many the governess put off from week to week and that they never got to

at all: she only used to say "We'll take that in its proper order." Her

order was a circle as vast as the untravelled globe. She had not the

spirit of adventure--the child could perfectly see how many subjects she

was afraid of. She took refuge on the firm ground of fiction, through

which indeed there curled the blue river of truth. She knew swarms of

stories, mostly those of the novels she had read; relating them with

a memory that never faltered and a wealth of detail that was Maisie's

delight. They were all about love and beauty and countesses and

wickedness. Her conversation was practically an endless narrative,

a great garden of romance, with sudden vistas into her own life and

gushing fountains of homeliness. These were the parts where they most

lingered; she made the child take with her again every step of her long,

lame course and think it beyond magic or monsters. Her pupil acquired a

vivid vision of every one who had ever, in her phrase, knocked against

her--some of them oh so hard!--every one literally but Mr. Wix, her

husband, as to whom nothing was mentioned save that he had been dead for

ages. He had been rather remarkably absent from his wife's career, and

Maisie was never taken to see his grave.

V

The second parting from Miss Overmore had been bad enough, but this

first parting from Mrs.

“Three things in human life are important: the first is to be kind; the second is to be kind; and the third is to be kind.”

“Life is what we make it, always has been, always will be.”

“Tea pot is on, the cups are waiting, Favorite chairs anticipating, No matter what I have to do, My friend theres always time for you”

“Bread and water can so easily be toast and tea”

“Where theres tea theres hope.”

“Come, let us have some tea and continue to talk about happy things.”

“Ive always been interested in people, but Ive never liked them.”

“It is art that makes life, makes interest, makes importance and I know of no substitute whatever for the force and beauty of its process.”

“Lifes too short for chess”

Im yours for ever--for ever and ever. Here I stand; Im as firm as a rock. If youll only trust me, how little youll be disappointed. Be mine as I am yours.