“I quarrel not with far-off foes, but with those who, near at home, co-operate with, and do the bidding of, those far away, and without whom the latter would be harmless.”

But Paley appears never to

have contemplated those cases to which the rule of expediency does not

apply, in which a people, as well as an individual, must do justice,

cost what it may. If I have unjustly wrested a plank from a drowning

man, I must restore it to him though I drown myself. This, according to

Paley, would be inconvenient. But he that would save his life, in such

a case, shall lose it. This people must cease to hold slaves, and to

make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people.

In their practice, nations agree with Paley; but does anyone think that

Massachusetts does exactly what is right at the present crisis?

“A drab of state, a cloth-o’-silver slut,

To have her train borne up, and her soul trail in the dirt.”

Practically speaking, the opponents to a reform in Massachusetts are

not a hundred thousand politicians at the South, but a hundred thousand

merchants and farmers here, who are more interested in commerce and

agriculture than they are in humanity, and are not prepared to do

justice to the slave and to Mexico, _cost what it may_. I quarrel not

with far-off foes, but with those who, near at home, co-operate with,

and do the bidding of those far away, and without whom the latter would

be harmless. We are accustomed to say, that the mass of men are

unprepared; but improvement is slow, because the few are not materially

wiser or better than the many. It is not so important that many should

be as good as you, as that there be some absolute goodness somewhere;

for that will leaven the whole lump. There are thousands who are _in

opinion_ opposed to slavery and to the war, who yet in effect do

nothing to put an end to them; who, esteeming themselves children of

Washington and Franklin, sit down with their hands in their pockets,

and say that they know not what to do, and do nothing; who even

postpone the question of freedom to the question of free-trade, and

quietly read the prices-current along with the latest advices from

Mexico, after dinner, and, it may be, fall asleep over them both. What

is the price-current of an honest man and patriot today? They hesitate,

and they regret, and sometimes they petition; but they do nothing in

earnest and with effect. They will wait, well disposed, for others to

remedy the evil, that they may no longer have it to regret.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes after work. But it is a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things..

Talk of a divinity in man! Look at the teamster on the

highway, wending to market by day or night; does any divinity stir

within him? His highest duty to fodder and water his horses! What is

his destiny to him compared with the shipping interests? Does not he

drive for Squire Make-a-stir? How godlike, how immortal, is he? See how

he cowers and sneaks, how vaguely all the day he fears, not being

immortal nor divine, but the slave and prisoner of his own opinion of

himself, a fame won by his own deeds. Public opinion is a weak tyrant

compared with our own private opinion. What a man thinks of himself,

that it is which determines, or rather indicates, his fate.

Self-emancipation even in the West Indian provinces of the fancy and

imagination,—what Wilberforce is there to bring that about? Think,

also, of the ladies of the land weaving toilet cushions against the

last day, not to betray too green an interest in their fates! As if you

could kill time without injuring eternity.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called

resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go

into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the

bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is

concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of

mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes after work. But it is

a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things.

When we consider what, to use the words of the catechism, is the chief

end of man, and what are the true necessaries and means of life, it

appears as if men had deliberately chosen the common mode of living

because they preferred it to any other. Yet they honestly think there

is no choice left. But alert and healthy natures remember that the sun

rose clear. It is never too late to give up our prejudices. No way of

thinking or doing, however ancient, can be trusted without proof. What

everybody echoes or in silence passes by as true to-day may turn out to

be falsehood to-morrow, mere smoke of opinion, which some had trusted

for a cloud that would sprinkle fertilizing rain on their fields. What

old people say you cannot do you try and find that you can. Old deeds

for old people, and new deeds for new. Old people did not know enough

once, perchance, to fetch fresh fuel to keep the fire a-going; new

people put a little dry wood under a pot, and are whirled round the

globe with the speed of birds, in a way to kill old people, as the

phrase is.

I learned this, at least, by my experiment; that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours..

It is not for a man to put himself in such an attitude to

society, but to maintain himself in whatever attitude he find himself

through obedience to the laws of his being, which will never be one of

opposition to a just government, if he should chance to meet with such.

I left the woods for as good a reason as I went there. Perhaps it

seemed to me that I had several more lives to live, and could not spare

any more time for that one. It is remarkable how easily and insensibly

we fall into a particular route, and make a beaten track for ourselves.

I had not lived there a week before my feet wore a path from my door to

the pond-side; and though it is five or six years since I trod it, it

is still quite distinct. It is true, I fear that others may have fallen

into it, and so helped to keep it open. The surface of the earth is

soft and impressible by the feet of men; and so with the paths which

the mind travels. How worn and dusty, then, must be the highways of the

world, how deep the ruts of tradition and conformity! I did not wish to

take a cabin passage, but rather to go before the mast and on the deck

of the world, for there I could best see the moonlight amid the

mountains. I do not wish to go below now.

I learned this, at least, by my experiment; that if one advances

confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the

life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in

common hours. He will put some things behind, will pass an invisible

boundary; new, universal, and more liberal laws will begin to establish

themselves around and within him; or the old laws be expanded, and

interpreted in his favor in a more liberal sense, and he will live with

the license of a higher order of beings. In proportion as he simplifies

his life, the laws of the universe will appear less complex, and

solitude will not be solitude, nor poverty poverty, nor weakness

weakness. If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be

lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.

It is a ridiculous demand which England and America make, that you

shall speak so that they can understand you. Neither men nor

toad-stools grow so. As if that were important, and there were not

enough to understand you without them. As if Nature could support but

one order of understandings, could not sustain birds as well as

quadrupeds, flying as well as creeping things, and _hush_ and _who_,

which Bright can understand, were the best English.

The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.

I do not mean to insist here on the disadvantage of hiring

compared with owning, but it is evident that the savage owns his

shelter because it costs so little, while the civilized man hires his

commonly because he cannot afford to own it; nor can he, in the long

run, any better afford to hire. But, answers one, by merely paying this

tax the poor civilized man secures an abode which is a palace compared

with the savage’s. An annual rent of from twenty-five to a hundred

dollars, these are the country rates, entitles him to the benefit of

the improvements of centuries, spacious apartments, clean paint and

paper, Rumford fireplace, back plastering, Venetian blinds, copper

pump, spring lock, a commodious cellar, and many other things. But how

happens it that he who is said to enjoy these things is so commonly a

_poor_ civilized man, while the savage, who has them not, is rich as a

savage? If it is asserted that civilization is a real advance in the

condition of man,—and I think that it is, though only the wise improve

their advantages,—it must be shown that it has produced better

dwellings without making them more costly; and the cost of a thing is

the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged

for it, immediately or in the long run. An average house in this

neighborhood costs perhaps eight hundred dollars, and to lay up this

sum will take from ten to fifteen years of the laborer’s life, even if

he is not encumbered with a family;—estimating the pecuniary value of

every man’s labor at one dollar a day, for if some receive more, others

receive less;—so that he must have spent more than half his life

commonly before _his_ wigwam will be earned. If we suppose him to pay a

rent instead, this is but a doubtful choice of evils. Would the savage

have been wise to exchange his wigwam for a palace on these terms?

It may be guessed that I reduce almost the whole advantage of holding

this superfluous property as a fund in store against the future, so far

as the individual is concerned, mainly to the defraying of funeral

expenses. But perhaps a man is not required to bury himself.

Nevertheless this points to an important distinction between the

civilized man and the savage; and, no doubt, they have designs on us

for our benefit, in making the life of a civilized people an

_institution_, in which the life of the individual is to a great extent

absorbed, in order to preserve and perfect that of the race.

It is not worth the while to let our imperfections disturb us always.

There is another kind of success than

his. Even here we have a sort of living to get, and must buffet it

somewhat longer. There are various tough problems yet to solve, and we

must make shift to live, betwixt spirit and matter, such a human life

as we can.

A healthy man, with steady employment, as wood-chopping at fifty cents

a cord, and a camp in the woods, will not be a good subject for

Christianity. The New Testament may be a choice book to him on some,

but not on all or most of his days. He will rather go a-fishing in his

leisure hours. The Apostles, though they were fishers too, were of the

solemn race of sea-fishers, and never trolled for pickerel on inland

streams.

Men have a singular desire to be good without being good for anything,

because, perchance, they think vaguely that so it will be good for them

in the end. The sort of morality which the priests inculcate is a very

subtle policy, far finer than the politicians, and the world is very

successfully ruled by them as the policemen. It is not worth the while

to let our imperfections disturb us always. The conscience really does

not, and ought not to monopolize the whole of our lives, any more than

the heart or the head. It is as liable to disease as any other part. I

have seen some whose consciences, owing undoubtedly to former

indulgence, had grown to be as irritable as spoilt children, and at

length gave them no peace. They did not know when to swallow their cud,

and their lives of course yielded no milk.

Conscience is instinct bred in the house,

Feeling and Thinking propagate the sin

By an unnatural breeding in and in.

I say, Turn it out doors,

Into the moors.

I love a life whose plot is simple,

And does not thicken with every pimple,

A soul so sound no sickly conscience binds it,

That makes the universe no worse than ’t finds it.

I love an earnest soul,

Whose mighty joy and sorrow

Are not drowned in a bowl,

And brought to life to-morrow;

That lives one tragedy,

And not seventy;

A conscience worth keeping,

Laughing not weeping;

A conscience wise and steady,

And forever ready;

Not changing with events,

Dealing in compliments;

A conscience exercised about

Large things, where one _may_ doubt.

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

The millions are awake enough for physical labor; but only one in a

million is awake enough for effective intellectual exertion, only one

in a hundred millions to a poetic or divine life. To be awake is to be

alive. I have never yet met a man who was quite awake. How could I have

looked him in the face?

We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical

aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn, which does not

forsake us in our soundest sleep. I know of no more encouraging fact

than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a

conscious endeavor. It is something to be able to paint a particular

picture, or to carve a statue, and so to make a few objects beautiful;

but it is far more glorious to carve and paint the very atmosphere and

medium through which we look, which morally we can do. To affect the

quality of the day, that is the highest of arts. Every man is tasked to

make his life, even in its details, worthy of the contemplation of his

most elevated and critical hour. If we refused, or rather used up, such

paltry information as we get, the oracles would distinctly inform us

how this might be done.

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front

only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it

had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not

lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor

did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I

wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so

sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to

cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and

reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then

to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness

to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be

able to give a true account of it in my next excursion. For most men,

it appears to me, are in a strange uncertainty about it, whether it is

of the devil or of God, and have _somewhat hastily_ concluded that it

is the chief end of man here to “glorify God and enjoy him forever.”

Still we live meanly, like ants; though the fable tells us that we were

long ago changed into men; like pygmies we fight with cranes; it is

error upon error, and clout upon clout, and our best virtue has for its

occasion a superfluous and evitable wretchedness.

If one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours. He will put some things behind, will pass an invisible boundary; new, universal, and more liberal laws will begin to establish themselves around and within him; or the old laws be expanded, and interpreted in his favor in a more liberal sense, and he will live with the license of a higher order of beings.

I left the woods for as good a reason as I went there. Perhaps it

seemed to me that I had several more lives to live, and could not spare

any more time for that one. It is remarkable how easily and insensibly

we fall into a particular route, and make a beaten track for ourselves.

I had not lived there a week before my feet wore a path from my door to

the pond-side; and though it is five or six years since I trod it, it

is still quite distinct. It is true, I fear that others may have fallen

into it, and so helped to keep it open. The surface of the earth is

soft and impressible by the feet of men; and so with the paths which

the mind travels. How worn and dusty, then, must be the highways of the

world, how deep the ruts of tradition and conformity! I did not wish to

take a cabin passage, but rather to go before the mast and on the deck

of the world, for there I could best see the moonlight amid the

mountains. I do not wish to go below now.

I learned this, at least, by my experiment; that if one advances

confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the

life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in

common hours. He will put some things behind, will pass an invisible

boundary; new, universal, and more liberal laws will begin to establish

themselves around and within him; or the old laws be expanded, and

interpreted in his favor in a more liberal sense, and he will live with

the license of a higher order of beings. In proportion as he simplifies

his life, the laws of the universe will appear less complex, and

solitude will not be solitude, nor poverty poverty, nor weakness

weakness. If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be

lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.

It is a ridiculous demand which England and America make, that you

shall speak so that they can understand you. Neither men nor

toad-stools grow so. As if that were important, and there were not

enough to understand you without them. As if Nature could support but

one order of understandings, could not sustain birds as well as

quadrupeds, flying as well as creeping things, and _hush_ and _who_,

which Bright can understand, were the best English. As if there were

safety in stupidity alone. I fear chiefly lest my expression may not be

_extra-vagant_ enough, may not wander far enough beyond the narrow

limits of my daily experience, so as to be adequate to the truth of

which I have been convinced.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes after work. But it is a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things.

Talk of a divinity in man! Look at the teamster on the

highway, wending to market by day or night; does any divinity stir

within him? His highest duty to fodder and water his horses! What is

his destiny to him compared with the shipping interests? Does not he

drive for Squire Make-a-stir? How godlike, how immortal, is he? See how

he cowers and sneaks, how vaguely all the day he fears, not being

immortal nor divine, but the slave and prisoner of his own opinion of

himself, a fame won by his own deeds. Public opinion is a weak tyrant

compared with our own private opinion. What a man thinks of himself,

that it is which determines, or rather indicates, his fate.

Self-emancipation even in the West Indian provinces of the fancy and

imagination,—what Wilberforce is there to bring that about? Think,

also, of the ladies of the land weaving toilet cushions against the

last day, not to betray too green an interest in their fates! As if you

could kill time without injuring eternity.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called

resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go

into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the

bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is

concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of

mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes after work. But it is

a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things.

When we consider what, to use the words of the catechism, is the chief

end of man, and what are the true necessaries and means of life, it

appears as if men had deliberately chosen the common mode of living

because they preferred it to any other. Yet they honestly think there

is no choice left. But alert and healthy natures remember that the sun

rose clear. It is never too late to give up our prejudices. No way of

thinking or doing, however ancient, can be trusted without proof. What

everybody echoes or in silence passes by as true to-day may turn out to

be falsehood to-morrow, mere smoke of opinion, which some had trusted

for a cloud that would sprinkle fertilizing rain on their fields. What

old people say you cannot do you try and find that you can. Old deeds

for old people, and new deeds for new. Old people did not know enough

once, perchance, to fetch fresh fuel to keep the fire a-going; new

people put a little dry wood under a pot, and are whirled round the

globe with the speed of birds, in a way to kill old people, as the

phrase is.

A written word is the choicest of relics. It is something at once more intimate with us and more universal than any other work of art. It is the work of art nearest to life itself. It may be translated into every language, and not only be read but actually breathed from all human lips; -- not be represented on canvas or in marble only, but be carved out of the breath of life itself.

What the Roman and Grecian

multitude could not _hear_, after the lapse of ages a few scholars

_read_, and a few scholars only are still reading it.

However much we may admire the orator’s occasional bursts of eloquence,

the noblest written words are commonly as far behind or above the

fleeting spoken language as the firmament with its stars is behind the

clouds. _There_ are the stars, and they who can may read them. The

astronomers forever comment on and observe them. They are not

exhalations like our daily colloquies and vaporous breath. What is

called eloquence in the forum is commonly found to be rhetoric in the

study. The orator yields to the inspiration of a transient occasion,

and speaks to the mob before him, to those who can _hear_ him; but the

writer, whose more equable life is his occasion, and who would be

distracted by the event and the crowd which inspire the orator, speaks

to the intellect and health of mankind, to all in any age who can

_understand_ him.

No wonder that Alexander carried the Iliad with him on his expeditions

in a precious casket. A written word is the choicest of relics. It is

something at once more intimate with us and more universal than any

other work of art. It is the work of art nearest to life itself. It may

be translated into every language, and not only be read but actually

breathed from all human lips;—not be represented on canvas or in marble

only, but be carved out of the breath of life itself. The symbol of an

ancient man’s thought becomes a modern man’s speech. Two thousand

summers have imparted to the monuments of Grecian literature, as to her

marbles, only a maturer golden and autumnal tint, for they have carried

their own serene and celestial atmosphere into all lands to protect

them against the corrosion of time. Books are the treasured wealth of

the world and the fit inheritance of generations and nations. Books,

the oldest and the best, stand naturally and rightfully on the shelves

of every cottage. They have no cause of their own to plead, but while

they enlighten and sustain the reader his common sense will not refuse

them. Their authors are a natural and irresistible aristocracy in every

society, and, more than kings or emperors, exert an influence on

mankind. When the illiterate and perhaps scornful trader has earned by

enterprise and industry his coveted leisure and independence, and is

admitted to the circles of wealth and fashion, he turns inevitably at

last to those still higher but yet inaccessible circles of intellect

and genius, and is sensible only of the imperfection of his culture and

the vanity and insufficiency of all his riches, and further proves his

good sense by the pains which he takes to secure for his children that

intellectual culture whose want he so keenly feels; and thus it is that

he becomes the founder of a family.

The question is not what you look at, but what you see.

We feel her heat and see her body darkening

over us. Our thoughts are not dissipated, but come back to us like an

echo.

The different kinds of moonlight are infinite. This is not a night for

contrasts of light and shade, but a faint diffused light in which there

is light enough to travel, and that is all.

A road (the Corner road) that passes over the height of land between

earth and heaven, separating those streams which flow earthward from

those which flow heavenward.

Ah, what a poor, dry compilation is the “Annual of Scientific

Discovery!” I trust that observations are made during the year which

are not chronicled there,—that some mortal may have caught a glimpse of

Nature in some corner of the earth during the year 1851. One sentence

of perennial poetry would make me forget, would atone for, volumes of

mere science. The astronomer is as blind to the significant phenomena,

or the significance of phenomena, as the wood-sawyer who wears glasses

to defend his eyes from sawdust. The question is not what you look at,

but what you see.

I hear now from Bear Garden Hill—I rarely walk by moonlight without

hearing—the sound of a flute, or a horn, or a human voice. It is a

performer I never see by day; should not recognize him if pointed

out; but you may hear his performance in every horizon. He plays but

one strain and goes to bed early, but I know by the character of that

single strain that he is deeply dissatisfied with the manner in which

he spends his day. He is a slave who is purchasing his freedom. He is

Apollo watching the flocks of Admetus on every hill, and this strain

he plays every evening to remind him of his heavenly descent. It is all

that saves him,—his one redeeming trait. It is a reminiscence; he loves

to remember his youth. He is sprung of a noble family. He is highly

related, I have no doubt; was tenderly nurtured in his infancy, poor

hind as he is. That noble strain he utters, instead of any jewel on his

finger, or precious locket fastened to his breast, or purple garments

that came with him.

If we will be quiet and ready enough, we shall find compensation in every disappointment.

How unaccountable the flow of spirits in youth. You may

throw sticks and dirt into the current, and it will only rise the

higher. Dam it up you may, but dry it up you may not, for you cannot

reach its source. If you stop up this avenue or that, anon it will come

gurgling out where you least expected and wash away all fixtures. Youth

grasps at happiness as an inalienable right. The tear does no sooner

gush than glisten. Who shall say when the tear that sprung of sorrow

first sparkled with joy?

ALMA NATURA

_Sept. 20._ It is a luxury to muse by a wall-side in the sunshine of

a September afternoon,—to cuddle down under a gray stone, and hearken

to the siren song of the cricket. Day and night seem henceforth but

accidents, and the time is always a still eventide, and as the close of

a happy day. Parched fields and mulleins gilded with the slanting rays

are my diet. I know of no word so fit to express this disposition of

Nature as Alma Natura.

COMPENSATION

_Sept. 23._ If we will be quiet and ready enough, we shall find

compensation in every disappointment. If a shower drives us for shelter

to the maple grove or the trailing branches of the pine, yet in their

recesses with microscopic eye we discover some new wonder in the bark,

or the leaves, or the fungi at our feet. We are interested by some

new resource of insect economy, or the chickadee is more than usually

familiar. We can study Nature's nooks and corners then.[40]

MY BOOTS

_Oct. 16._

Anon with gaping fearlessness they quaff

The dewy nectar with a natural thirst,

Or wet their leathern lungs where cranberries lurk,

With sweeter wine than Chian, Lesbian, or Falernian far.

Theirs was the inward lustre that bespeaks

An open sole—unknowing to exclude

The cheerful day—a worthier glory far

Than that which gilds the outmost rind with darkness visible—

Virtues that fast abide through lapse of years,

Rather rubbed in than off.

HOMER

_Oct. 21._ Hector hurrying from rank to rank is likened to the moon

wading in majesty from cloud to cloud.

All men want, not something to do with, but something to do, or rather something to be.

A man who has at length found something to do will not need to get a

new suit to do it in; for him the old will do, that has lain dusty in

the garret for an indeterminate period. Old shoes will serve a hero

longer than they have served his valet,—if a hero ever has a

valet,—bare feet are older than shoes, and he can make them do. Only

they who go to soirées and legislative halls must have new coats, coats

to change as often as the man changes in them. But if my jacket and

trousers, my hat and shoes, are fit to worship God in, they will do;

will they not? Who ever saw his old clothes,—his old coat, actually

worn out, resolved into its primitive elements, so that it was not a

deed of charity to bestow it on some poor boy, by him perchance to be

bestowed on some poorer still, or shall we say richer, who could do

with less? I say, beware of all enterprises that require new clothes,

and not rather a new wearer of clothes. If there is not a new man, how

can the new clothes be made to fit? If you have any enterprise before

you, try it in your old clothes. All men want, not something to _do

with_, but something to _do_, or rather something to _be_. Perhaps we

should never procure a new suit, however ragged or dirty the old, until

we have so conducted, so enterprised or sailed in some way, that we

feel like new men in the old, and that to retain it would be like

keeping new wine in old bottles. Our moulting season, like that of the

fowls, must be a crisis in our lives. The loon retires to solitary

ponds to spend it. Thus also the snake casts its slough, and the

caterpillar its wormy coat, by an internal industry and expansion; for

clothes are but our outmost cuticle and mortal coil. Otherwise we shall

be found sailing under false colors, and be inevitably cashiered at

last by our own opinion, as well as that of mankind.

We don garment after garment, as if we grew like exogenous plants by

addition without. Our outside and often thin and fanciful clothes are

our epidermis, or false skin, which partakes not of our life, and may

be stripped off here and there without fatal injury; our thicker

garments, constantly worn, are our cellular integument, or cortex; but

our shirts are our liber or true bark, which cannot be removed without

girdling and so destroying the man.

The language of Friendship is not words, but meanings.

It

is a miracle which requires constant proofs. It is an exercise of the

purest imagination and the rarest faith. It says by a silent but

eloquent behavior,—“I will be so related to thee as thou canst imagine;

even so thou mayest believe. I will spend truth,—all my wealth on

thee,”—and the Friend responds silently through his nature and life,

and treats his Friend with the same divine courtesy. He knows us

literally through thick and thin. He never asks for a sign of love, but

can distinguish it by the features which it naturally wears. We never

need to stand upon ceremony with him with regard to his visits. Wait

not till I invite thee, but observe that I am glad to see thee when

thou comest. It would be paying too dear for thy visit to ask for it.

Where my Friend lives there are all riches and every attraction, and no

slight obstacle can keep me from him. Let me never have to tell thee

what I have not to tell. Let our intercourse be wholly above ourselves,

and draw us up to it.

The language of Friendship is not words, but meanings. It is an

intelligence above language. One imagines endless conversations with

his Friend, in which the tongue shall be loosed, and thoughts be spoken

without hesitancy or end; but the experience is commonly far otherwise.

Acquaintances may come and go, and have a word ready for every

occasion; but what puny word shall he utter whose very breath is

thought and meaning? Suppose you go to bid farewell to your Friend who

is setting out on a journey; what other outward sign do you know than

to shake his hand? Have you any palaver ready for him then? any box of

salve to commit to his pocket? any particular message to send by him?

any statement which you had forgotten to make?—as if you could forget

anything.—No, it is much that you take his hand and say Farewell; that

you could easily omit; so far custom has prevailed. It is even painful,

if he is to go, that he should linger so long. If he must go, let him

go quickly. Have you any _last_ words? Alas, it is only the word of

words, which you have so long sought and found not; _you_ have not a

_first_ word yet.

There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root.

If you give money, spend

yourself with it, and do not merely abandon it to them. We make curious

mistakes sometimes. Often the poor man is not so cold and hungry as he

is dirty and ragged and gross. It is partly his taste, and not merely

his misfortune. If you give him money, he will perhaps buy more rags

with it. I was wont to pity the clumsy Irish laborers who cut ice on

the pond, in such mean and ragged clothes, while I shivered in my more

tidy and somewhat more fashionable garments, till, one bitter cold day,

one who had slipped into the water came to my house to warm him, and I

saw him strip off three pairs of pants and two pairs of stockings ere

he got down to the skin, though they were dirty and ragged enough, it

is true, and that he could afford to refuse the _extra_ garments which

I offered him, he had so many _intra_ ones. This ducking was the very

thing he needed. Then I began to pity myself, and I saw that it would

be a greater charity to bestow on me a flannel shirt than a whole

slop-shop on him. There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil

to one who is striking at the root, and it may be that he who bestows

the largest amount of time and money on the needy is doing the most by

his mode of life to produce that misery which he strives in vain to

relieve. It is the pious slave-breeder devoting the proceeds of every

tenth slave to buy a Sunday’s liberty for the rest. Some show their

kindness to the poor by employing them in their kitchens. Would they

not be kinder if they employed themselves there? You boast of spending

a tenth part of your income in charity; maybe you should spend the nine

tenths so, and done with it. Society recovers only a tenth part of the

property then. Is this owing to the generosity of him in whose

possession it is found, or to the remissness of the officers of

justice?

Philanthropy is almost the only virtue which is sufficiently

appreciated by mankind. Nay, it is greatly overrated; and it is our

selfishness which overrates it. A robust poor man, one sunny day here

in Concord, praised a fellow-townsman to me, because, as he said, he

was kind to the poor; meaning himself.

We are constantly invited to be what we are.

After this we are not surprised

when he concludes by saying: "The society of young women is the most

unprofitable I have ever tried." No, no; he was nothing like Mr. Samuel

Pepys.

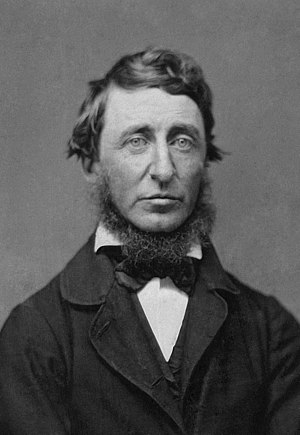

The sect of young women, we may add, need not feel deeply affronted by

this ungallant mention. It is perhaps the only one of its kind in the

journal (by its nature restricted to matters interesting to the author),

while there are multitudes of passages to prove that Thoreau's aversion

to the society of older people taken as they run, men and women alike,

was hardly less pronounced. In truth (and it is nothing of necessity

against him), he was not made for "parties," nor for clubs, nor even for

general companionship. "I am all without and in sight," said Montaigne,

"born for society and friendship." So was not Thoreau. He was all

within, born for contemplation and solitude. And what we are born for,

that let us be,—and so the will of God be done. Such, for good or ill,

was Thoreau's philosophy. "We are constantly invited to be what we are,"

he said. It is one of his memorable sentences; an admirable summary of

Emerson's essay on Self-Reliance.

His fellow mortals, as a rule, did not recommend themselves to him. His

thoughts were none the better for their company, as they almost always

were for the company of the pine tree and the meadow. Inspiration, a

refreshing of the spiritual faculties, as indispensable to him as daily

bread, that his fellow mortals did not furnish him. For this state of

things he sometimes (once or twice at least) mildly reproaches himself.

It may be that he is to blame for so commonly skipping humanity and its

affairs; he will seek to amend the fault, he promises. But even at such

a moment of exceptional humility, his pen, reversing Balaam's rôle,

runs into left-handed compliments that are worse, if anything, than

the original offense. Hear him: "I will not avoid to go by where those

men are repairing the stone bridge. I will see if I cannot see poetry

in that, if that will not yield me a reflection.

Public opinion is a weak tyrant compared with our own private opinion. what a man thinks of himself, that it is which determines, or rather indicates, his fate.

It is very evident

what mean and sneaking lives many of you live, for my sight has been

whetted by experience; always on the limits, trying to get into

business and trying to get out of debt, a very ancient slough, called

by the Latins _æs alienum_, another’s brass, for some of their coins

were made of brass; still living, and dying, and buried by this other’s

brass; always promising to pay, promising to pay, tomorrow, and dying

today, insolvent; seeking to curry favor, to get custom, by how many

modes, only not state-prison offences; lying, flattering, voting,

contracting yourselves into a nutshell of civility or dilating into an

atmosphere of thin and vaporous generosity, that you may persuade your

neighbor to let you make his shoes, or his hat, or his coat, or his

carriage, or import his groceries for him; making yourselves sick, that

you may lay up something against a sick day, something to be tucked

away in an old chest, or in a stocking behind the plastering, or, more

safely, in the brick bank; no matter where, no matter how much or how

little.

I sometimes wonder that we can be so frivolous, I may almost say, as to

attend to the gross but somewhat foreign form of servitude called Negro

Slavery, there are so many keen and subtle masters that enslave both

north and south. It is hard to have a southern overseer; it is worse to

have a northern one; but worst of all when you are the slave-driver of

yourself. Talk of a divinity in man! Look at the teamster on the

highway, wending to market by day or night; does any divinity stir

within him? His highest duty to fodder and water his horses! What is

his destiny to him compared with the shipping interests? Does not he

drive for Squire Make-a-stir? How godlike, how immortal, is he? See how

he cowers and sneaks, how vaguely all the day he fears, not being

immortal nor divine, but the slave and prisoner of his own opinion of

himself, a fame won by his own deeds. Public opinion is a weak tyrant

compared with our own private opinion. What a man thinks of himself,

that it is which determines, or rather indicates, his fate.

Self-emancipation even in the West Indian provinces of the fancy and

imagination,—what Wilberforce is there to bring that about? Think,

also, of the ladies of the land weaving toilet cushions against the

last day, not to betray too green an interest in their fates! As if you

could kill time without injuring eternity.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called

resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go

into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the

bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is

concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of

mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes after work. But it is

a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things.

When we consider what, to use the words of the catechism, is the chief

end of man, and what are the true necessaries and means of life, it

appears as if men had deliberately chosen the common mode of living

because they preferred it to any other.

As if you could kill time without injuring eternity.

It is hard to have a southern overseer; it is worse to

have a northern one; but worst of all when you are the slave-driver of

yourself. Talk of a divinity in man! Look at the teamster on the

highway, wending to market by day or night; does any divinity stir

within him? His highest duty to fodder and water his horses! What is

his destiny to him compared with the shipping interests? Does not he

drive for Squire Make-a-stir? How godlike, how immortal, is he? See how

he cowers and sneaks, how vaguely all the day he fears, not being

immortal nor divine, but the slave and prisoner of his own opinion of

himself, a fame won by his own deeds. Public opinion is a weak tyrant

compared with our own private opinion. What a man thinks of himself,

that it is which determines, or rather indicates, his fate.

Self-emancipation even in the West Indian provinces of the fancy and

imagination,—what Wilberforce is there to bring that about? Think,

also, of the ladies of the land weaving toilet cushions against the

last day, not to betray too green an interest in their fates! As if you

could kill time without injuring eternity.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called

resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go

into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the

bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is

concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of

mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes after work. But it is

a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things.

When we consider what, to use the words of the catechism, is the chief

end of man, and what are the true necessaries and means of life, it

appears as if men had deliberately chosen the common mode of living

because they preferred it to any other. Yet they honestly think there

is no choice left. But alert and healthy natures remember that the sun

rose clear. It is never too late to give up our prejudices. No way of

thinking or doing, however ancient, can be trusted without proof. What

everybody echoes or in silence passes by as true to-day may turn out to

be falsehood to-morrow, mere smoke of opinion, which some had trusted

for a cloud that would sprinkle fertilizing rain on their fields.

In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of Brahma and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.

Thus for sixteen days I saw from my window a hundred men at work like

busy husbandmen, with teams and horses and apparently all the

implements of farming, such a picture as we see on the first page of

the almanac; and as often as I looked out I was reminded of the fable

of the lark and the reapers, or the parable of the sower, and the like;

and now they are all gone, and in thirty days more, probably, I shall

look from the same window on the pure sea-green Walden water there,

reflecting the clouds and the trees, and sending up its evaporations in

solitude, and no traces will appear that a man has ever stood there.

Perhaps I shall hear a solitary loon laugh as he dives and plumes

himself, or shall see a lonely fisher in his boat, like a floating

leaf, beholding his form reflected in the waves, where lately a hundred

men securely labored.

Thus it appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New

Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well. In the

morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal

philosophy of the Bhagvat Geeta, since whose composition years of the

gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and

its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is

not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its

sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book and go to my well

for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of

Brahma and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the Ganges

reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and

water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and

our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden

water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges. With favoring

winds it is wafted past the site of the fabulous islands of Atlantis

and the Hesperides, makes the periplus of Hanno, and, floating by

Ternate and Tidore and the mouth of the Persian Gulf, melts in the

tropic gales of the Indian seas, and is landed in ports of which

Alexander only heard the names.

Spring

The opening of large tracts by the ice-cutters commonly causes a pond

to break up earlier; for the water, agitated by the wind, even in cold

weather, wears away the surrounding ice. But such was not the effect on

Walden that year, for she had soon got a thick new garment to take the

place of the old. This pond never breaks up so soon as the others in

this neighborhood, on account both of its greater depth and its having

no stream passing through it to melt or wear away the ice. I never knew

it to open in the course of a winter, not excepting that of ’52–3,

which gave the ponds so severe a trial. It commonly opens about the

first of April, a week or ten days later than Flint’s Pond and

Fair-Haven, beginning to melt on the north side and in the shallower

parts where it began to freeze.

Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star.

Every one has heard the story which has gone the rounds of

New England, of a strong and beautiful bug which came out of the dry

leaf of an old table of apple-tree wood, which had stood in a farmer’s

kitchen for sixty years, first in Connecticut, and afterward in

Massachusetts,—from an egg deposited in the living tree many years

earlier still, as appeared by counting the annual layers beyond it;

which was heard gnawing out for several weeks, hatched perchance by the

heat of an urn. Who does not feel his faith in a resurrection and

immortality strengthened by hearing of this? Who knows what beautiful

and winged life, whose egg has been buried for ages under many

concentric layers of woodenness in the dead dry life of society,

deposited at first in the alburnum of the green and living tree, which

has been gradually converted into the semblance of its well-seasoned

tomb,—heard perchance gnawing out now for years by the astonished

family of man, as they sat round the festive board,—may unexpectedly

come forth from amidst society’s most trivial and handselled furniture,

to enjoy its perfect summer life at last!

I do not say that John or Jonathan will realize all this; but such is

the character of that morrow which mere lapse of time can never make to

dawn. The light which puts out our eyes is darkness to us. Only that

day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is

but a morning star.

THE END

ON THE DUTY OF CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE

I heartily accept the motto,—“That government is best which governs

least;” and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and

systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I

believe—“That government is best which governs not at all;” and when

men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they

will have. Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments

are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient. The

objections which have been brought against a standing army, and they

are many and weighty, and deserve to prevail, may also at last be

brought against a standing government. The standing army is only an arm

of the standing government. The government itself, which is only the

mode which the people have chosen to execute their will, is equally

liable to be abused and perverted before the people can act through it.

Witness the present Mexican war, the work of comparatively a few

individuals using the standing government as their tool; for, in the

outset, the people would not have consented to this measure.

To be a philosopher is not merely to have subtle thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so to love wisdom as to live according to its dictates, a life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity and trust.

The luxuriously

rich are not simply kept comfortably warm, but unnaturally hot; as I

implied before, they are cooked, of course _à la mode_.

Most of the luxuries, and many of the so called comforts of life, are

not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of

mankind. With respect to luxuries and comforts, the wisest have ever

lived a more simple and meagre life than the poor. The ancient

philosophers, Chinese, Hindoo, Persian, and Greek, were a class than

which none has been poorer in outward riches, none so rich in inward.

We know not much about them. It is remarkable that _we_ know so much of

them as we do. The same is true of the more modern reformers and

benefactors of their race. None can be an impartial or wise observer of

human life but from the vantage ground of what we should call voluntary

poverty. Of a life of luxury the fruit is luxury, whether in

agriculture, or commerce, or literature, or art. There are nowadays

professors of philosophy, but not philosophers. Yet it is admirable to

profess because it was once admirable to live. To be a philosopher is

not merely to have subtle thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so

to love wisdom as to live according to its dictates, a life of

simplicity, independence, magnanimity, and trust. It is to solve some

of the problems of life, not only theoretically, but practically. The

success of great scholars and thinkers is commonly a courtier-like

success, not kingly, not manly. They make shift to live merely by

conformity, practically as their fathers did, and are in no sense the

progenitors of a nobler race of men. But why do men degenerate ever?

What makes families run out? What is the nature of the luxury which

enervates and destroys nations? Are we sure that there is none of it in

our own lives? The philosopher is in advance of his age even in the

outward form of his life. He is not fed, sheltered, clothed, warmed,

like his contemporaries. How can a man be a philosopher and not

maintain his vital heat by better methods than other men?

When a man is warmed by the several modes which I have described, what

does he want next? Surely not more warmth of the same kind, as more and

richer food, larger and more splendid houses, finer and more abundant

clothing, more numerous incessant and hotter fires, and the like.