“One ought to seek out virtue for its own sake, without being influenced by fear or hope, or by any external influence. Moreover, that in that does happiness consist.”

For our individual natures are all parts

of universal nature; on which account the chief good is to live in a

manner corresponding to nature, and that means corresponding to one’s

own nature and to universal nature; doing none of those things which the

common law of mankind is in the habit of forbidding, and that common law

is identical with that right reason which pervades everything, being the

same with Jupiter, who is the regulator and chief manager of all existing

things.

Again, this very thing is the virtue of the happy man and the perfect

happiness of life when everything is done according to a harmony

with the genius of each individual with reference to the will of the

universal governor and manager of all things. Diogenes, accordingly, says

expressly that the chief good is to act according to sound reason in our

selection of things according to our nature. And Archedemus defines it

to be living in the discharge of all becoming duties. Chrysippus again

understands that the nature, in a manner corresponding to which we ought

to live, is both the common nature, and also human nature in particular;

but Cleanthes will not admit of any other nature than the common one

alone, as that to which people ought to live in a manner corresponding;

and repudiates all mention of a particular nature. And he asserts

that virtue is a disposition of the mind always consistent and always

harmonious; that one ought to seek it out for its own sake, without being

influenced by fear or hope by any external influence. Moreover, that it

is in it that happiness consists, as producing in the soul the harmony

of a life always consistent with itself; and that if a rational animal

goes the wrong way, it is because it allows itself to be misled by the

deceitful appearances of exterior things, or perhaps by the instigation

of those who surround it; for nature herself never gives us any but good

inclinations.

LIV. Now virtue is, to speak generally, a perfection in everything, as

in the case of a statue; whether it is invisible as good health, or

speculative as prudence. For Hecaton says, in the first book of his

treatise on Virtues, that the scientific and speculative virtues are

those which have a constitution arising from speculation and study,

as, for instance, prudence and justice; and that those which are not

speculative are those which are generally viewed in their extension as a

practical result or effect of the former; such for instance, as health

and strength. Accordingly, temperance is one of the speculative virtues,

and it happens that good health usually follows it, and is marshalled

as it were beside it; in the same way as strength follows the proper

structure of an arch.

“I know nothing, except the fact of my ignorance”

He used to praise leisure as the most valuable of possessions,

as Xenophon tells us in his Banquet. And it was a saying of his that

there was one only good, namely, knowledge; and one only evil, namely,

ignorance; that riches and high birth had nothing estimable in them, but

that, on the contrary, they were wholly evil. Accordingly, when some one

told him that the mother of Antisthenes was a Thracian woman, “Did you

suppose,” said he, “that so noble a man must be born of two Athenians?”

And when Phædo was reduced to a state of slavery, he ordered Crito to

ransom him, and taught him, and made him a philosopher.

XV. And, moreover, he used to learn to play on the lyre when he had time,

saying, that it was not absurd to learn anything that one did not know;

and further, he used frequently to dance, thinking such an exercise good

for the health of the body, as Xenophon relates in his Banquet.

XVI. He used also to say that the dæmon foretold the future to him;[21]

and that to begin well was not a trifling thing, but yet not far from

a trifling thing; and that he knew nothing, except the fact of his

ignorance. Another saying of his was, that those who bought things out of

season, at an extravagant price, expected never to live till the proper

season for them. Once, when he was asked what was the virtue of a young

man, he said, “To avoid excess in everything.” And he used to say, that

it was necessary to learn geometry only so far as might enable a man to

measure land for the purposes of buying and selling. And when Euripides,

in his Auge, had spoken thus of virtue:—

’Tis best to leave these subjects undisturbed;

he rose up and left the theatre, saying that it was an absurdity to

think it right to seek for a slave if one could not find him, but to

let virtue be altogether disregarded. The question was once put to him

by a man whether he would advise him to marry or not? And he replied,

“Whichever you do, you will repent it.” He often said, that he wondered

at those who made stone statues, when he saw how careful they were that

the stone should be like the man it was intended to represent, but how

careless they were of themselves, as to guarding against being like the

stone.

“It takes a wise man to discover a wise man”

He lived to an extreme old age; as

he says somewhere himself:—

Threescore and seven long years are fully passed,

Since first my doctrines spread abroad through Greece:

And ’twixt that time and my first view of light

Six lustres more must added be to them:

If I am right at all about my age,

Lacking but eight years of a century.

His doctrine was, that there were four elements of existing things; and

an infinite number of worlds, which were all unchangeable. He thought

that the clouds were produced by the vapour which was borne upwards from

the sun, and which lifted them up into the circumambient space. That the

essence of God was of a spherical form, in no respect resembling man;

that the universe could see, and that the universe could hear, but could

not breathe; and that it was in all its parts intellect, and wisdom, and

eternity. He was the first person who asserted that everything which is

produced is perishable, and that the soul is a spirit. He used also to

say that the many was inferior to unity. Also, that we ought to associate

with tyrants either as little as possible, or else as pleasantly as

possible.

When Empedocles said to him that the wise man was undiscoverable, he

replied, “Very likely; for it takes a wise man to discover a wise

man.” And Sotion says, that he was the first person who asserted that

everything is incomprehensible. But he is mistaken in this.

Xenophanes wrote a poem on the Founding of Colophon; and also, on the

Colonisation of Elea, in Italy, consisting of two thousand verses. And he

flourished about the sixtieth olympiad.

IV. Demetrius Phalereus, in his treatise on Old Age, and Phenætius the

Stoic, in his essay on Cheerfulness, relate that he buried his sons

with his own hands, as Anaxagoras had also done. And he seems to have

been detested[123] by the Pythagoreans, Parmeniscus, and Orestades, as

Phavorinus relates in the first book of his Commentaries.

V. There was also another Xenophanes, a native of Lesbos, and an iambic

poet.

These are the Promiscuous or unattached philosophers.

LIFE OF PARMENIDES.

I. Parmenides, the son of Pyres, and a citizen of Velia, was a pupil of

Xenophanes. And Theophrastus, in his Abridgment, says that he was also a

pupil of Anaximander. However, though he was a pupil of Xenophanes, he

was not afterwards a follower of his; but he attached himself to Aminias,

and Diochaetes the Pythagorean, as Sotion relates, which last was a poor

but honourable and virtuous man.

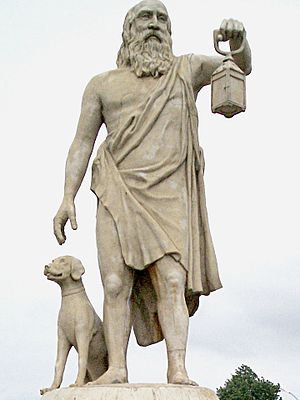

“Discourse on virtue and they pass by in droves. Whistle and dance the shimmy, and youve got an audience.”

“As a matter of self-preservation, a man needs good friends or ardent enemies, for the former instruct him and the latter take him to task.”

“We have two ears and one tongue so that we would listen more and talk less”

“I threw my cup away when I saw a child drinking from his hands at the trough.”

“Dogs and philosophers do the greatest good and get the fewest rewards”

“No man is hurt but by himself”

“He has the most who is most content with the least”

“When I look upon seamen, men of science and philosophers, man is the wisest of all beings; when I look upon priests and prophets nothing is as contemptible as man”

“The foundation of every state is the education of its youth.”

“Man is the most intelligent of the animals -- and the most silly.”

“I have nothing to ask but that you would remove to the other side, that you may not, by intercepting the sunshine, take from me what you cannot give”

“Blushing is the color of virtue.”

“A friend is one soul abiding in two bodies”

Calumny is only the noise of madmen.

The only good is knowledge and the only evil ignorance.

Of a rich man who was mean and niggardly he said That man does hot possess his estate but his estate possesses him.

Thales was asked what was most difficult to man he answered: To know ones self.